The Salvadoran town where migrants are hotly debated folk heroes

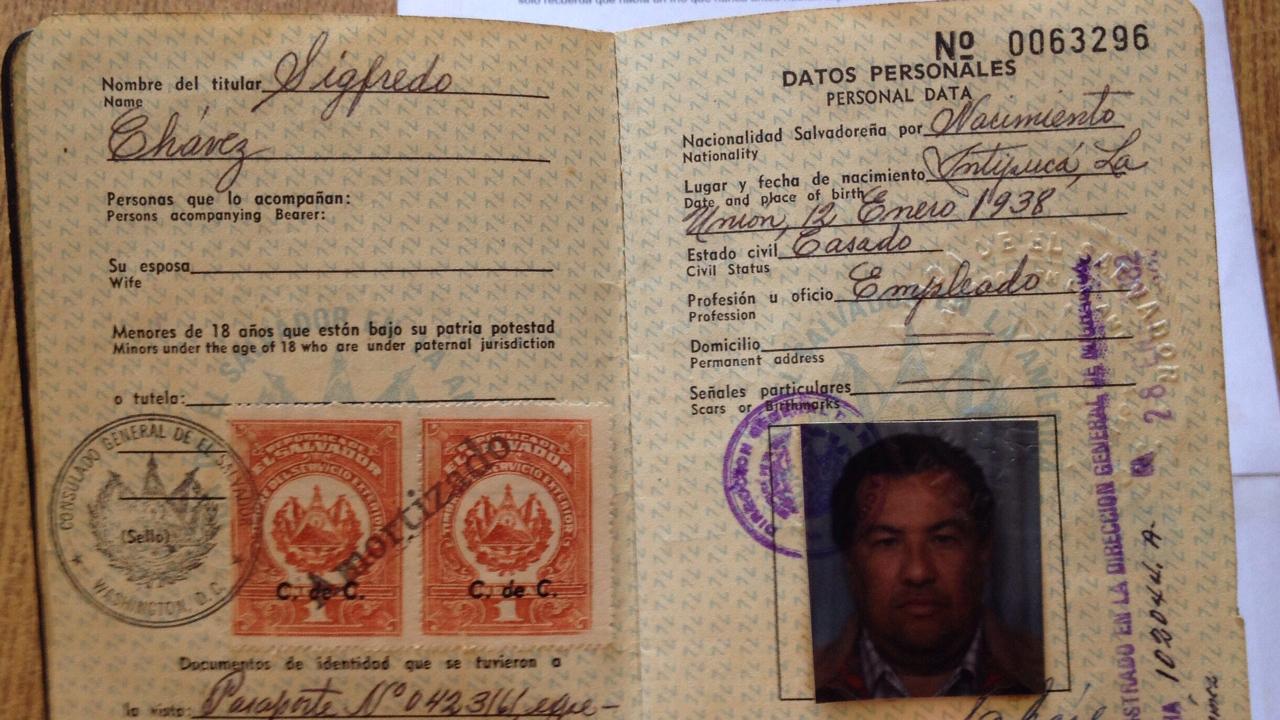

A passport that belonged to Sigfredo Chávez. Intipucá celebrates him as its first migrant to take off for the US.

Intipucá is a small town in southeastern El Salvador that lies close to a beach popular with surfers. But the reason most outsiders know about this place has nothing to do with tourism. Intipucá is famous for the people who have left.

An estimated 5,000 Intipucá locals now live in and around Washington, DC. The mayor, Enrique Méndez, gave me his version of why people started leaving the town en masse for the US.

The mayor’s story isn’t quite right. The migration began in the late 1960s, at least 15 years before El Salvador descended into civil war. And when he says Sigfredo Chávez was the town’s first migrant, several people in his office start to disagree.

It turns out that the story of Intipucá’s first migrant is part reality, part gossip and part legend.

One person who claims to know the real story is Oscar Romero, Sigfredo Chávez’s nephew. Early on a weekday morning, before he heads out to work, Romero meets me in front of the monument erected in his uncle’s honor in Intipucá’s main plaza.

Looking up at the clay statue of man with a backpack slung over his shoulder, Romero is clearly filled with pride.

“It’s the first monument to emigrants in the world!” he says. “Nowhere else did people have the idea to praise their first migrant. So my uncle now is an international symbol!”

Chávez is definitely something of a folk hero in Intipucá. “He’s fit and athletic,” Romero says, pointing to the statue. “You see his character traits on his face: Confident, driven. He’s headed north, in the direction of the airport.”

Chávez came from a landowning family that hit some hard times after El Salvador’s agrarian reform. According to the story, his mother, an ambitious woman, pushed him to go the US to improve the family’s fortunes. Romero says his uncle left town in 1968 with a tourist visa; the first migrant from Intipucá didn’t cross the US-Mexico border illegally on foot, like so many others after him.

He went to Washington, DC, and his stories started filtering back a few months later. You could make a good living doing dishes and cleaning homes, he said.

Many locals started to follow, and within a few years, Washington became the top destination for Intipucá natives. Some people in the town say about 300 people were leaving for the US every day, though that’s clearly an exaggeration.

No matter the numbers, remittances from Washington began to flow back to Intipucá. They eventually paid for a school, a stadium and a cultural center, so having a connection to the first migrant means bragging rights here.

“It’s like an award. It’s like saying I win the prize because my family was the first to migrate,” says Jaqueline Portillo, director of Intipucá’s cultural center and the guardian of many of the local families’ artifacts, documents and photos. Inside her locked desk drawer are Chávez’s old passports, his divorce papers and family photos.

So it's no wonder Chávez's family isn’t the only one to claim the number-one spot.

Alfredito Arias insists he was the first to leave, in 1967, but he won’t consent to an interview. He says he’s done trying to make his case to strangers.

“The Chávez family kept better documentation than Alfredito Arias,” Portillo says, “so there’s simply more weight to the story of Chávez being the first migrant.”

Chávez died in 2006, so he can’t tell his own story. But his widow, Elba Salinas, is still alive in the US. Her nephew, Hugo Salinas, says she should be credited as the first migrant — Chávez wouldn’t have left for the US if it hadn't been for her.

“He left with Elba!” Salinas insists. “Elba told me so!”

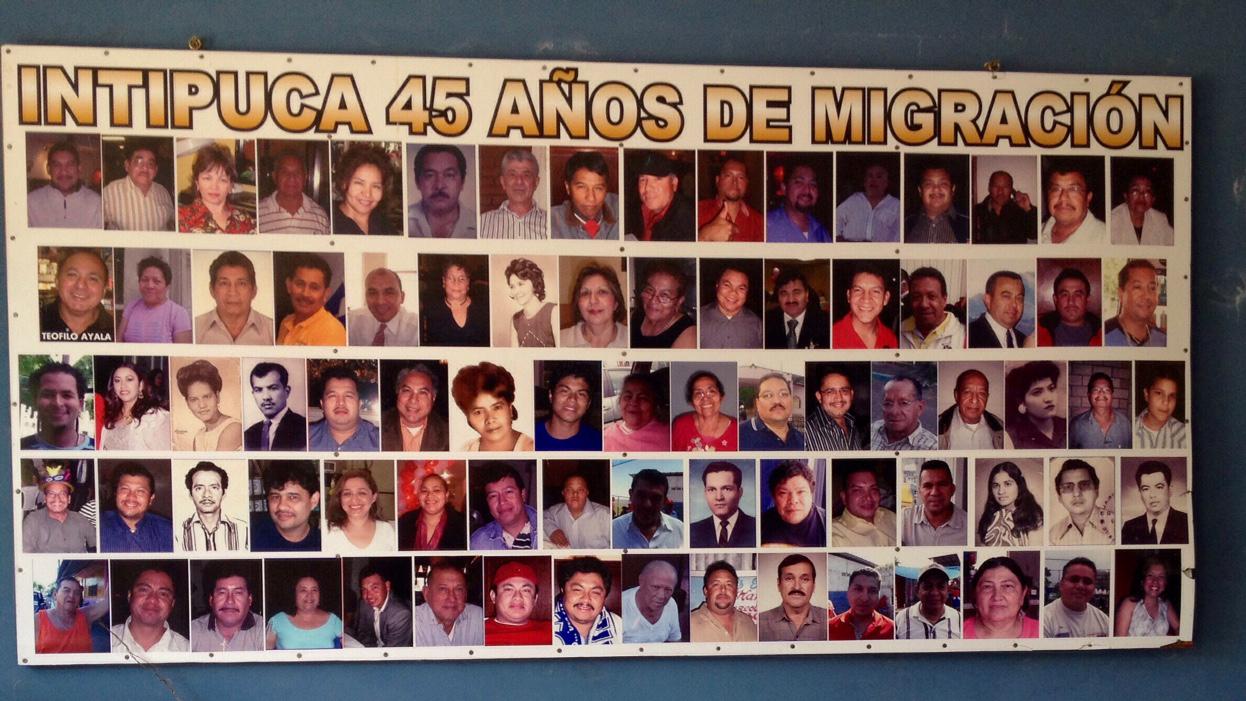

Salinas is collecting the details of his aunt’s story, and those of many other Intipucá migrants as well. He and Jaqueline Portillo are planning a big event for the 50th anniversary of migration in Intipucá, which is coming up in 2018.

“I want to create a positive image of my town, because no one was collecting these personal stories,” Salinas says. “Stories like the one of Mr. Martin Lazo, who would lend you a suit to get on a flight because you had to dress nicely back then. Or the story of ‘Travel Today, Pay Later,' which would give you a loan so you could pay for your US visa.”

Salinas is worried these stories about immigration and Intipucá will be forgotten in the next few generations. Today, an estimated half of the town’s population is living in US. The streets are largely empty. Even Sigredo Chavez’s home is abandoned, another monument to a town that celebrates its own exodus.

Ruxandra's story was produced in association with Round Earth Media. Jimmy Alvarado of El Faro contributed to the reporting.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!