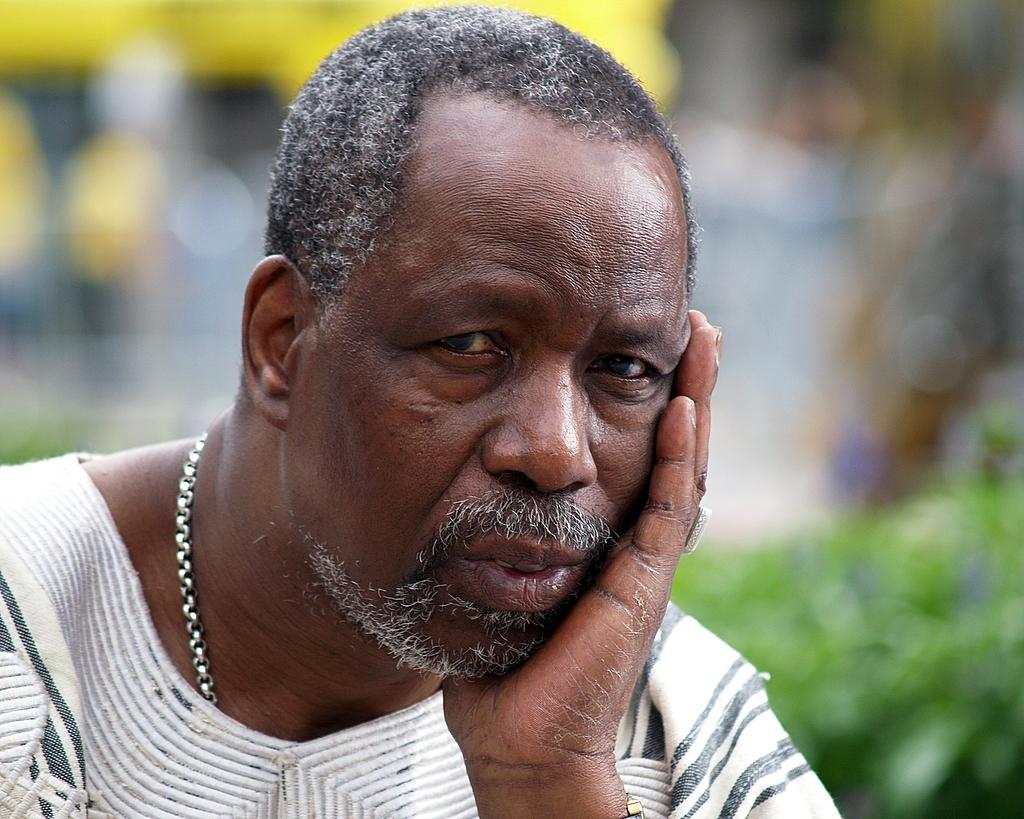

Lamine Touré, the founder and owner of Club Balatou in Montreal.

On Thursday night, Montreal will host a sort of world music battle of the bands. Three groups will duke it out for a coveted trophy called the Syli D’Or, which means “the Golden Elephant.”

The concerts are hosted by Club Balattou, a tiny place along St. Laurent, one of Montreal’s main drags. As soon as you walk in the door, you’re looking directly at musicians on stage. In fact, you have to walk right in front of the stage to get a drink at the bar.

Club Balattou is a legendary spot, one of the first venues to bring African bands to North America in the 1980s. Little has changed here over the years: same mirrors on the ceiling and walls, same ’80s logo in purple neon splashed over the bar. Even the carpet is the original from when Balattou opened in 1985.

As a Guinean band, Thousand Colors, kicks in, a man with darting eyes and a black ski cap hunches by the door. He wears a baggy fleece over an African batik. Occasionally he offers a handshake or a hug, or leans in to share a confidence as stragglers wander in.

You’d never know he's Lamine Touré, Club Balattou’s owner and founder, a sort of godfather of African music in Canada.

In the ’80s, Touré lured some of Africa’s biggest stars to play in little Balattou when they were selling out stadiums in their home countries. Papa Wemba and Baaba Maal made North American debuts here. Salif Keita, Yossou N’Dour and Angelique Kidjo made early appearances here, as did Lokteo, a Congolese soukous band.

"Lamine Touré is the wise man of the neighborhood," says Montreal-based music journalist Ralph Boncy. "He’s a magician. He’s not fast. He’s always slow. He always has advice for you."

Touré didn’t grant interviews for years, and he’s still not one to tell much of his own story. But Boncy says Touré’s quiet wisdom made Balattou the prime gathering place for African immigrants in Montreal in the 1990s.

"It’s like the light by the shore, always faithful to guide Black culture and the diasporas," Boncy says.

Touré was born in Guinea to a successful African trader. He followed his father on trips to Mali, Senegal, Congo and many other countries, learning the language of business. When he was 13, he became a dancer with Les Ballets Africains, the national ballet of Guinea, and toured across Africa and Europe.

He absorbed the differences in African cultures, says Suzanne Rousseau, who started working at Club Balattou soon after it opened — but also what ties those cultures together.

Rousseau says Touré became an encyclopedia of musical roots: "He tells you exactly the origin [of the music], from which country. Soca, calypso, for example, it came from the High Life of Ghana. He makes all these connections."

In 1974, Touré moved to Montreal, where he met Alex Boicel, the son of a jazz club owner. Together they opened Café Creole, a place for African and Caribbean immigrants to talk politics and share music. Boicel says Touré would hold court in his quiet way.

"Touré would tell you so many things about Africa," he says. "You don’t even have to go to the book and read it. That was the pure story."

Touré became a father figure to Boicel. They helped immigrants navigate working papers and permits, and kept a couple of beds in the back for people just off the plane. Those immigrants in turn brought in the latest records from overseas.

"If you want to hear music from Congo, from Cameroon, Guinea, Mali, Senegal, this is the place to be," Boicel says. "All the students, those who were very homesick for their country, were coming there."

When Café Creole closed, Touré decided to open a club of his own. "I wanted to make something that automatically said it was a club for everyone, all races and cultures," Touré says. So he coined a word in French: Balattou, or Bal-a-tous — “dance party for all.”

Balattou became a must-stop for African musicians, and Congolese artist Dally Kimoko even wrote a song about it, called "Balattou a Montreal."

Each summer, Club Balattou holds a festival all over Montreal that attracts almost 200,000 people. It’s called Nuits D’Afrique, and it showcases world-famous acts from Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean.

But it’s the Syli D’Or battle of the bands that nurtures the next generation.

The Guinean band Yammousa Kora and Thousand Colors face a Mexican Son Jarocho band and a Chilean electro-Andean DJ in the finals on April 30. The grand prize includes free studio time and $2,000 in radio promotion. The real winners, though, are the people who love music without borders.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!