Earthquakes create as well as destroy

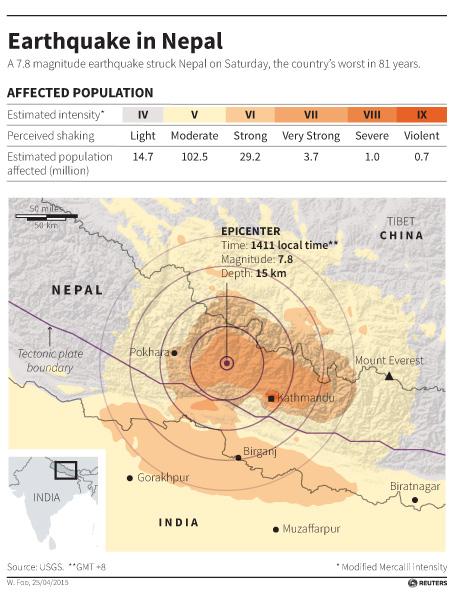

A Nepalese army personnel stands in front of a collapsed temple in Bhaktapur, Nepal a day after the April 25 earthquake rocked the country. The quake devastated the heavily crowded Kathmandu valley, killing thousands and triggering a deadly avalanche on Mount Everest.

There is another side to this story.

It’s hard to write about the creative power of earthquakes amid the awful destruction and loss of life that we’re seeing in Nepal. The human misery and economic damage are front and center in coverage of such tragedies, as they should be.

But when such disaster strikes it actually helps — helps me, anyway — to keep the long view in mind. Along with their awesome destructive power, earthquakes, and the slow, inexorable drifting and grinding of the earth’s massive plates that cause them, help make our planet what it is: fascinating, diverse, beautiful, habitable.

An earth without earthquakes would be an earth without the dramatic coasts of Alaska and the Pacific Northwest, Tierra del Fuego, and Kamchatka. An earth without distinct continents and many of their unique animals, plants and landscapes. An earth possibly without even a breathable atmosphere. (Plate tectonics, through earthquakes and their kin volcanos, release huge amounts of gases into the air, including carbon dioxide, the raw material of photosynthesis, which releases oxygen.)

Earthquakes churn up minerals from the depths that are vital to life and valuable to humans. They create valleys, lakes, bays, and oceans — diverse habitats for life to thrive and differentiate.

And they create mountains.

Imagine the earth without the Rockies, the Alps, the Andes. The Himalayas, in which Nepal and its unique culture and spectacular beauty, rest. Everest itself. The mountain on which so many died in Saturday’s quake-caused avalanche was created by earthquakes. Mighty Everest, the tallest peak on earth, may even be a little taller this week than last. A little more of a challenge to draw humans back.

The earthquakes — shifting, cracking, buckling of the earth’s crust — that formed and continue to form Everest, Nepal and the Himalayas are caused by the immense energy of the ongoing collision of the northward-drifting Indian subcontinent with Asia, a violent merging of the two land masses that began roughly 50 million years ago and continues at an average of roughly five centimeters a year. It proceeds in mostly tiny fits and starts, pressure and tension building up in the rocks of the earth’s crust until finally some of it is released. The land shakes, buildings collapse, people die, the Himalayas grow. And India marches north. American scientists say part of India pushed one to 10 feet into Asia on Saturday.

But that massive, slow-motion collision does more than build the region’s mountains. It’s responsible for landforms, ecosystems and even political geography thousands of miles away. One I happen to know a fair amount about, because I wrote a book about it, is Russia’s Lake Baikal, in southern Siberia, 2,000 miles northeast of Nepal.

Baikal is the world’s deepest lake and largest body of fresh water, holding roughly a fifth of all the liquid fresh water on the surface of the earth, as much as all of North America’s Great Lakes combined. It's also a cauldron of evolution, a sort of inland Galapagos with almost 2,000 plants and animals that live nowhere else.

Baikal lies in a rift zone, a cracked, weak spot in the earth’s crust that’s been slowly collapsing and splitting open over at least 25 million years. The region has its own peculiar geology, but many geologists believe that the energy that drives the processes that created the lake and continue to expand it — one day, they think, it may grow to split eastern Siberia in two and open into the Arctic Ocean—comes from that massive continental mash-up to the south.

And then there is Siberia itself, a place generations of Russian prisoners and exiles have been sent to be gotten out of the way, disappear, die. A place synonymous with remote, uninhabitable, frozen hell on earth.

As with Baikal, many factors contribute to Siberia’s unfortunate place in the world’s mind. But one is its topography.

Siberia is largely one gigantic, continent-sized swampy forest. A main reason for that is that all of its rivers run north, toward the Arctic. That means the mouths of those rivers are the last part of their systems to thaw every spring. Which in turn means that instead of draining easily into the ocean, the rivers back up, spill over, waterlog the landscape, and make it difficult to build on or even farm. And the reason all those rivers flow north is that the collision of India with Asia has pushed the southern part of the Asian landmass up, causing a long, slow, northward slope from Tibet all the way to the Arctic.

Imagine a world without earthquakes and you imagine a world without Siberia.

All these processes of plate tectonics, continental collisions, upthrust, mountain-building, play out over millions and even billions of years. A single earthquake plays out in a matter of minutes, even seconds. The earth-shaking events that bring untold hardship to people are just a blip in the unimaginably long history of a planet constantly reshaping itself.

Knowing this does nothing to help the dead and suffering in Nepal, it does nothing to help the country recover, and it certainly does nothing to keep such a thing from happening again. Hopefully even writing about it so soon after the quake won’t seem callous to some readers.

But for someone half a world away, who can do nothing else but watch, send money and maybe help send a reporter to tell stories of the affected people and places, it is strangely comforting. With destruction by nature comes creation by nature. Some people suffer, others benefit. But the earth doesn’t care or measure. We live on an amazing, ever-changing planet that’s indifferent to the fate of individuals, species, civilizations.

In the face of what we do to the earth, some greens like to remind us that nature always wins in the end. I prefer to think of it as nature just doing what nature does, creating and re-creating a place where life for us humans is not just possible, but where, for the most part, it’s fantastic.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!