What links the global Internet? Wires inside tubes no bigger than a garden hose.

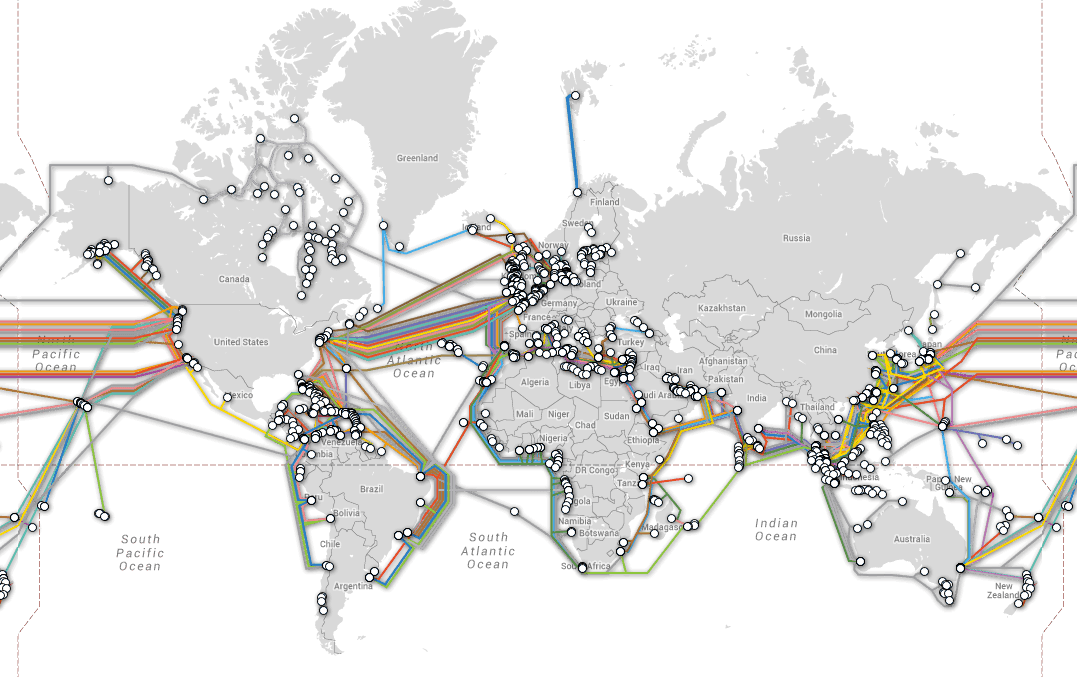

A screenshot of the interactive Submarine Cable Map, which tracks active and planned submarine cable systems and their landing stations according to the Global Bandwidth Research Service.

With cell phone, Wi-Fi and Bluetooth almost everywhere, it sometimes seems like we’ve finally ditched the cumbersome cords that are tethering us and our gadgets to Earth. But in reality, we live in a world that’s more wired than ever before — it's just that those wires are strung along the bottom of the world’s oceans.

“Ninety-nine percent of trans-oceanic data traffic, Internet traffic, goes underneath the ocean on the very bottom of the sea floor,” says Nicole Starosielski, an assistant professor of media, culture and communication at New York University. She’s the author of "The Undersea Network," a book exploring this hidden world of cable.

The scale of the network is both superhuman and surprisingly mundane at the same time. The wires are strung along the ocean bed by large tankers, which carry enough cable to go across the entire Atlantic Ocean. But the cables themselves aren't that big.

“It’s about the size of a garden hose,” Starosielski says. “In Guam, for example, the cables run right over the shoreline. … People step over them looking for the tourist attraction down the beach … [and] have no idea the Internet is pulsing right underneath their feet.”

And that's why the biggest threat to these cables is humans, not sharks or other sea life. “The majority of the disruptions of our undersea network come from people dropping an anchor off their boat and hitting the cable, or a fisherman dragging a net on the bottom of the sea floor,” Starosielski explains — not exactly the usual cause that comes to mind when Google fails to reload.

The cables seemingly haven’t been targets for terrorists thus far. “Some in the industry speculate that is because they’re not a visible target,” says Starosielski, but it also could be due to a lack of reporting. She notes one incident off the coast of Egypt in 2008 when multiple cables broke in succession.

“This looked very suspicious,” she says. Though reports indicated the damage was due to ships dropping anchors in the area, videos didn’t show any vessels in the area at the right time. The resulting outage was huge, disconnecting approximately 60 million people in India, 12 million in Pakistan, six million in Egypt and almost five million in Saudi Arabia.

“There are certainly people who are worrying about the fact that our cable network isn’t totally diverse, and there are these critical single points of failure,” Starosielski says.

The Arctic Fibre Project, which is exploring laying fiber-optic cables in the Arctic Ocean, would help combat the lack of diversity. “We’ve never had a cable that has gone through the Arctic Ocean," Starosielski says. The cables would link Japan to the United Kingdom could zap data from one end to the other in just 154 milliseconds.

But terrorism or human error aside, the cables were built to last. They can withstand the inhospitable ocean floor for 25 years, and, as Starosielski notes, “what else of the Internet has been instituted and stayed the same for 25 years?"

This story is based on an interview from PRI's Science Friday with Ira Flatow.