Members of a Right to Light campaign in Hidalgo County, Texas, where many of the colonias along the border lack street lights.

The word colonia means "neighborhood" in Spanish, but when people say colonia in the Rio Grande Valley, they’re talking about the makeshift communities — more than 1,000 — that have sprung up just north of the US-Mexico border.

Developers buy land, divide it up and sell the plots, mostly to Mexican immigrants. Some have legal status, some don't.

At first, all they got was land: No water, no paved roads, electricity or drainage. But over the past 30 years, colonias have become neighborhoods. Residents organized, fought for improvements and won.

They have at least one big fight left: The right to light.

When I visit the Curry Estates Colonia in Hidalgo County, Texas, on a recent night, I can’t see my car keys in my hand. I can’t see where the fence ends and the street begins. I can’t even see the ground under my feet.

“Once you step out on the street, it’s nothing," says Emma Alaniz, a native of Monterrey, Mexico. "It’s all dark, all dark,”

Alaniz has lived in Curry Estates for 15 years, raised two kids here. That’s one of the reasons she responded when an organizer stuck a flyer in her mailbox four years ago, looking for volunteers for a “Right to Light” campaign. There aren’t any playgrounds or sidewalks in the colonias or sidewalks, so "we have to drive very, very careful because there’s a lot of children and some of them play really late outside,” Alaniz says.

There are also free-roaming dogs that treat the bumpers of cars like oversized chew toys. At least mine, anyway.

“The other thing is the crime,” Alaniz says. “We have to be careful about that, too.”

That’s the irony here: As a nation, we’re security-obsessed when it comes to the US-Mexico border. But we don’t pay much attention to what goes on right next to it.

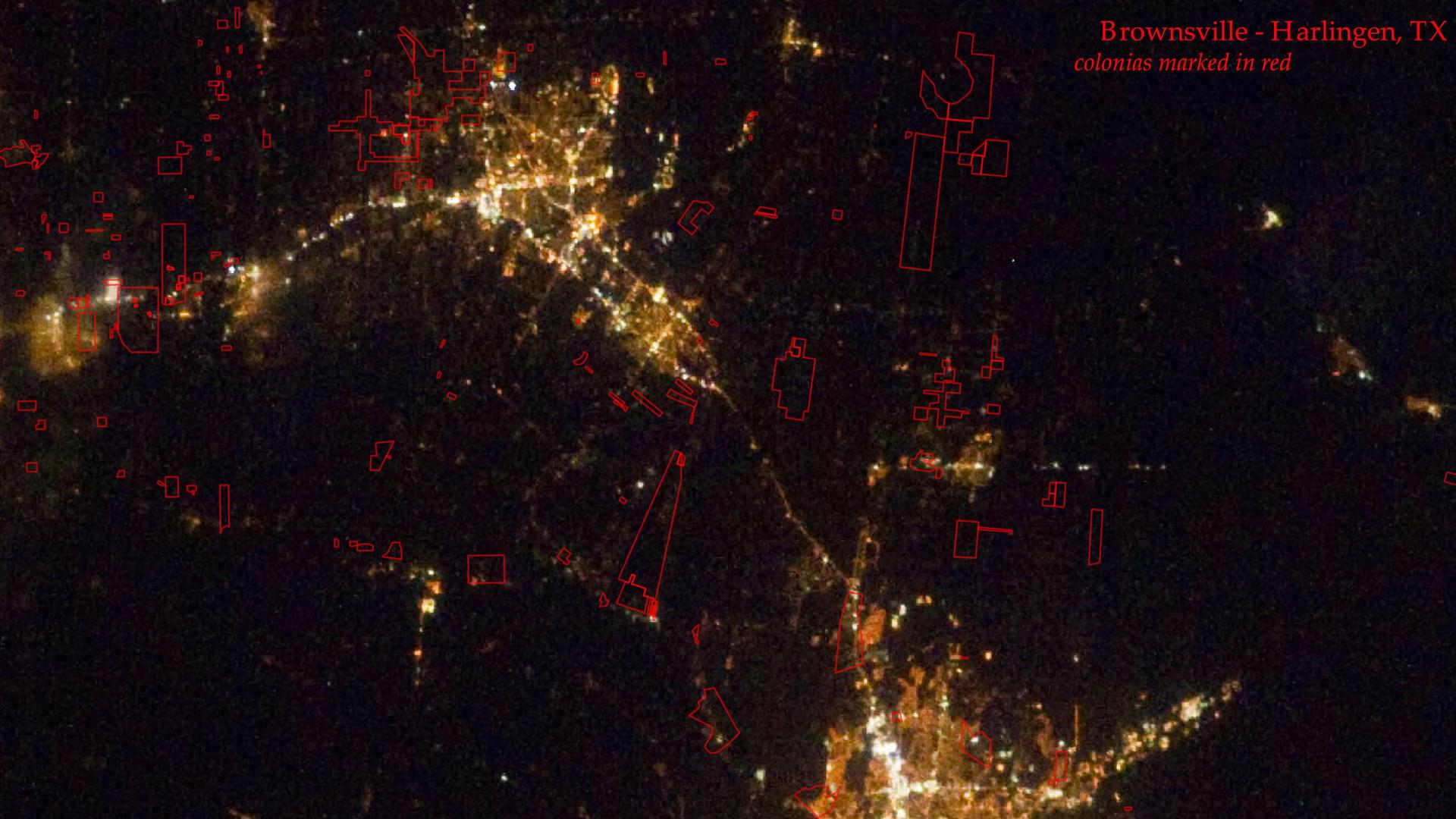

If you look at satellite photos of Hidalgo County, what lies beyond the wall are miles of darkness. Activists and residents point out that void exacerbates problems like undocumented immigration and border-gang violence.

But to Juanita Valdez-Cox, the director of LUPE, a local community organization that's backing the Right to Light campaign, the problem is also about equality and fairness. “When you buy a piece of property and build your home or buy your home, you don’t have to worry whether it has street lights," she says.

And sometimes, when colonia residents buy their lots, existing streetlights don't stay on. “You know what they do?” Valdez-Cox asks. “The developer sells the lot and they have the street lights and they have the poles and it’s lighted. And once they sell the lots, they turn off the light.”

That makes the developers sound like the bad guys, and some of them are. But without them there’s practically no other source of low-incoming housing in the county. And they’re not legally obligated to provide street lights.

So why hasn’t local government done something about this? They tried in 2012. Hidalgo County used federal grant money to test out solar street lights in a handful of colonias. It didn’t work out so well. The solar lights were expensive and too dim, and there wasn’t enough money to maintain them.

“Once they broke, they broke,” Emma Alaniz, the colonia resident, explains, “so we’re asking for the regular lights.”

There’s an underlying metaphor here: These communities don’t want to occupy some kind of gray zone. They want to be integrated, connected to the grid. The electric grid, sure, but also to their local government — and the rest of America too.

Why is this so hard? I ask Jaime Longoria, the assistant chief administrator for the county judge.

“Certainly we realize that there’s value in safety,” he tells me, “but it becomes an issue of the thousands and thousands of subdivisions that are out there. How do we light up each and every one of those particular corners, each one of those streets? Counties are strapped as it is. Someone’s going to have to pay for that.”

In the second-poorest county in the country, figuring out who that “someone” should be is a problem. The county thought the residents should help foot that bill. The residents originally thought otherwise, but they recently decided to meet the government halfway.

“We’re really close to agreement that it should be part of your tax bill,” says Juanita Valdez-Cox of LUPE.

They’re about to file a bill in the coming legislative session that would add a lighting surcharge to the tax bill for colonia residents. If it passes, the county would move forward with a $500,000 pilot program. And that means that people living in the colonias may finally come out of the shadows — literally.