Could Charlie Hebdo happen in Reykjavik? How Iceland’s Muslims try to convince people it won’t

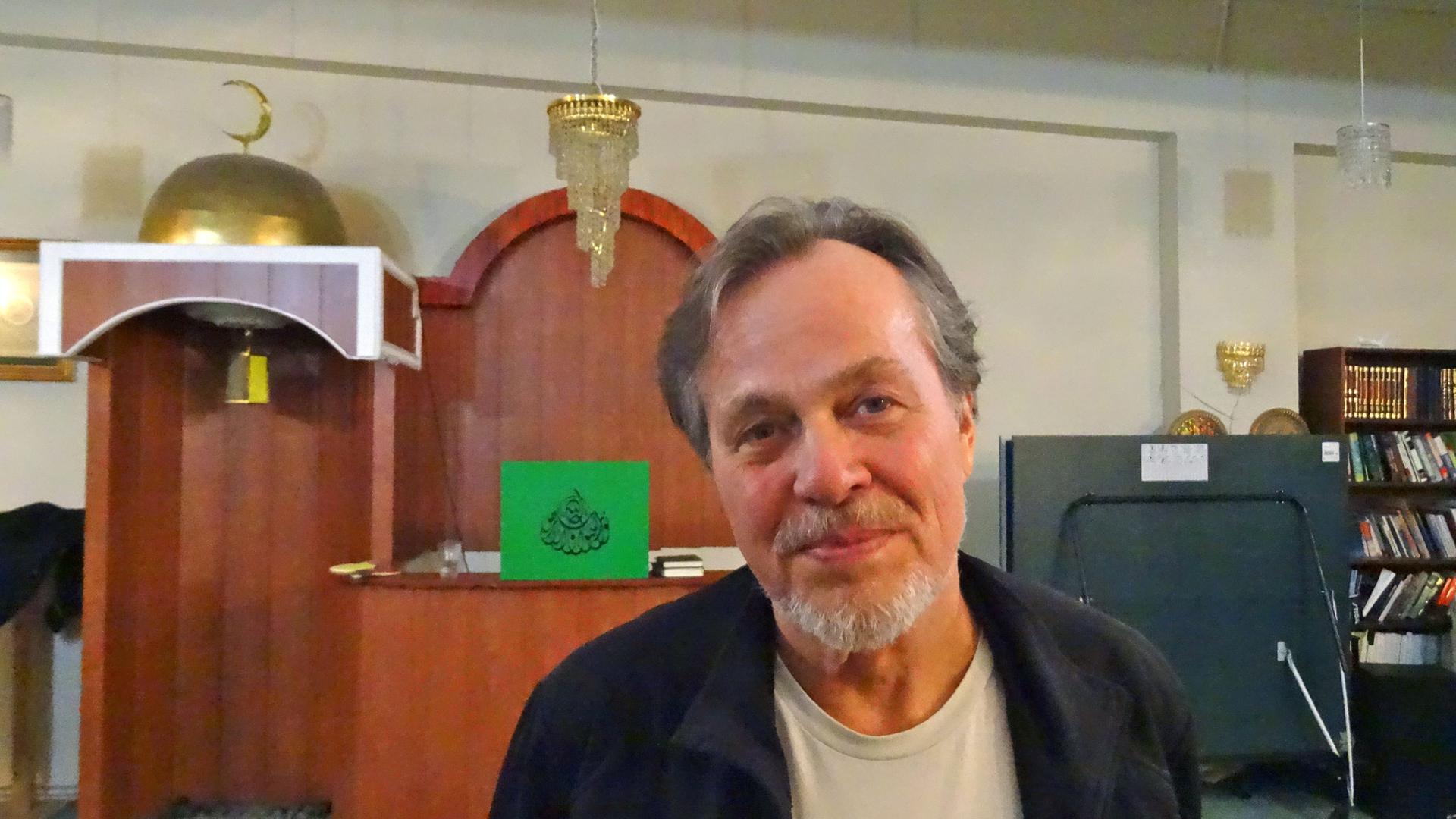

Sverrir Ibrahim Agnarsson, chairman of the Muslim Association of Iceland, inside the group's makeshift mosque in Reykjavik.

For more than a thousand years, Iceland barely had any visitors. There were the colonizers — Norwegians, then Danes, then the US military — plus a few eccentric adventurers, but that was about it.

That’s changed in the last 20 years. Today the streets of Reykjavik are teeming with non-Icelanders. Most are tourists, but there are also migrants, who now make up about eight percent of Iceland’s population. Among them are at least 1,200 Muslims.

“Nobody thinks I’m a Muslim,” said Somali-born Yassin Hassan. “Most people think I’m an American basketball player. When I tell them my name is Yassin, they start to get the picture.”

Hassan was one of a half-dozen men I met on a snowy evening in Reykjavik. The others were an Eritrean, two Danes of Turkish ancestry, an Iraqi and a Syrian. They had come to pray at a makeshift mosque tucked between a piano school and a discount picture framing store in a commercial district of Reykjavik.

“I love extreme weather and extreme wind,” said Muhammed Kizilkaya, a sociology student. He’s from Denmark, born to Turkish-Kurdish parents. No one else shared his views on the local climate.

“It’s tough,” said Hassan of the winter’s darkness. “Depression, no Somalis here. The only community you have is the mosque. You have to come to mosque and chat with people.”

That mosque is due for an upgrade. The Muslim Association of Iceland is working in co-operation with the Association of Icelandic Architects on plans for the country’s first custom-built mosque, constructed on land donated by the city of Reykjavik. The mosque and its minaret would have size restrictions, but it would accommodate at least 300 worshippers, according the Muslim Association’s chairman, Sverrir Ibrahim Agnarsson.

“In most other countries in Europe, you usually have a Moroccan mosque, a Syrian mosque, a Turkish mosque and a Pakistani mosque,” Agnarsson said. But not in Iceland: The size of the local Muslim population couldn’t support that. And Agnarsson enjoys the mix of nationalities and styles.

“We are all from all over and we try to keep it like it like that,” he said. “We keep it simple. This mosque is just for praying and the usual things that Muslims do — marry, you die, get buried, you have the Eid festivals here. That’s the function of the mosque.”

Icelanders are still getting used to Islam in their own backyard. A poll last year found that 42 percent of those surveyed opposed the construction of a mosque. One party made opposition to the mosque its main campaign issue during Reykjavik’s most recent municipal elections. They did better than expected, winning two seats on the city council.

“There is a very hardcore opposition to Islam and Muslims in Iceland, basically inspired by this Islamophobic literature from America,” Agnarsson said. “When this political party took this card out of their sleeve and tried to increase their following, they did. But we also got a lot of sympathy.”

Agnarsson says he finds himself online almost every day conversing about Islam with other Icelanders, sometimes explaining the religion, sometimes defending it. “I make my jihad on the computer keyboard,“ he tells me with a smile.

But defending the faith doesn’t come so easily to Yassin Hassan. He escaped violence in Somalia, and now he says he finds himself pegged as the worshipper of a violent religion. The questions from Icelanders have been especially pointed after the fatal jihadist attacks in Paris and Copenhagen.

“Sometimes you’re sitting on your sofa at home and you’re trying to watch TV, and you hope — you pray — that something doesn’t happen in the Middle East because it’s going to affect you here,” Hassan said. “What happened in a couple of European countries the last two months, you have to explain to the people that that is not Islam. You have to explain to the people, ‘I hate these people as much as you do. Don’t put us in the same category.’ It’s sometimes boring, but you have to do that.”

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!