Up close, ‘Earth-like’ planets are still wildly unfamiliar worlds

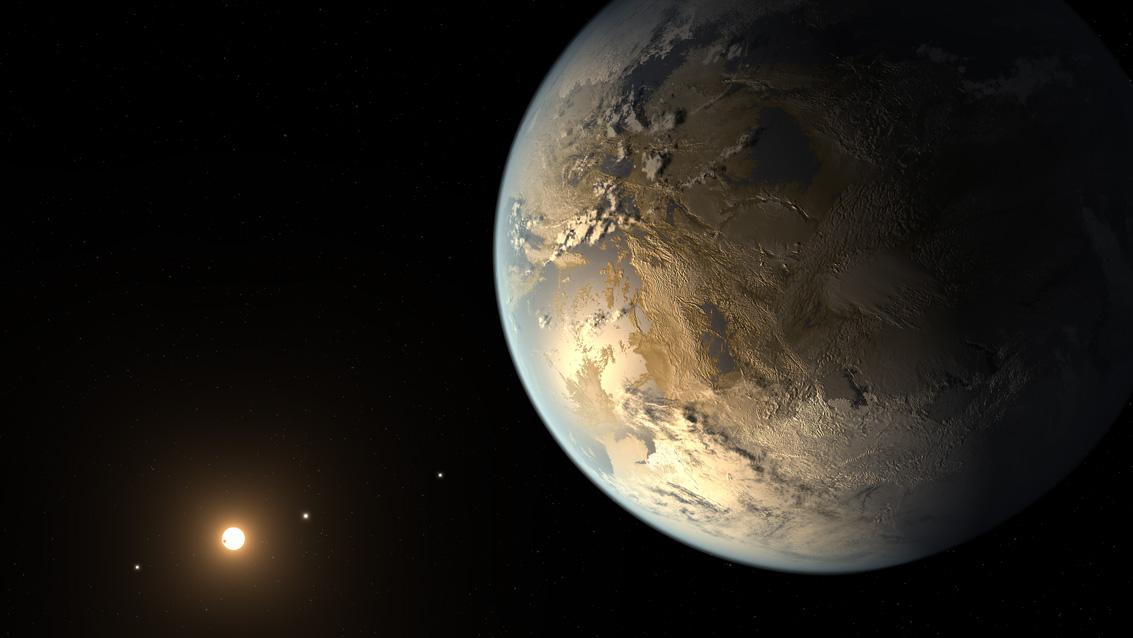

An artist's rendering if Kepler 186f, a world extremely similar to Kepler 438b, an Earth-like exoplanet orbiting an M-class dwarf star in the habitable zone.

Of the hundreds of new planets the Kepler Space Telescope has found, only a handful have been considered very "Earth-like." One of them is Kepler-438b, about 470 light-years from Earth.

“At first glance, this appears to be a planet very much like Earth,” says Natalie Batalha, an astronomer at NASA’s Ames Research Center and a Kepler Mission scientist. “It’s about the same size — it’s only about 10 percent larger than the Earth in its radius. It receives about the same amount of energy from its star that Earth receives from its sun."

But that's the view from 470 light-years away. "As we travel there and take a closer look, we start to notice some big difference," Batalha says.

For starters, Kepler-438b's star is very different from our sun: It's an M-class dwarf star that's small, dim, and ruddy. “It’s about half the size of our sun and it’s about 2,000 degrees cooler than our own sun,” Batalha says. “It’s emitting mostly red and infrared radiation as opposed to the yellow, visible light that our own sun emits."

Batalha says M-class dwarf stars have intense magnetic fields that give rise to sunspots and coronal mass ejections. We seee those massive bursts of magnetically charged gasses emerge from our own sun, but with M-class dwarf stars, things are exaggerated tenfold.

If a human were to theoretically stand on the surface of Kepler-438b, she would see a spectacular light show in the sky because of that intense solar activity, much like what we on Earth know as the Northern and Southern Lights.

But while the star could produce a beautiful night sky, Batalha explains its prospects for producing life are much tougher.

“What we know is that all life is carbon-based, and carbon-based chemistry requires water for its survival,” she says. “We’re looking for planets where water can pool on the surface. But if you’ve got a central start with such a low luminosity — only four percent of the Sun’s luminosity — you’re going to have to cozy up close to that star to create those conditions.”

Because of the size and dimness of an M-class dwarf star, Kepler-438b — or any other potentially habitable planet — would need to be very close in order to get the right amount of energy to have liquid water on the surface.

Being so close to the star would subject Kepler-438b to strong tidal forces. Batalha says they would likely lock the planet into a synchronous rotation, meaning only one side of the planet would face the star — and that could create some extremely alien environments.

“The Earth is kind of like a rotisserie chicken," she says. "It’s spinning on its axis and it gets nicely toasted on all sides. If you have a planet that’s locked in a synchronous rotation, than that rotisserie chicken is only getting cooked on one side."

Batalha says the Kepler-438b's atmosphere could circulate, bringing heat from the sunny side to the other side of the planet. Oceans on the dayside might also evaporate under the constant sun, creating clouds that could shield the planet's surface. But while that would make it more hospitable to life, there would be other effects.

The clouds on Kepler-438b might initially work to cool the surface of the planet, Batalha says, but that model would not be sustainable in the long term.

“You would start getting that circulation and you’d push that warm air over to the back side. And then what’s going to happen? It’s going condense, rain out — maybe even freeze," she says. "With time, slowly but surely, what I imagine might happen is the oceans on the dayside might gradually evaporate away and you would start piling up all of that water in a frozen state on the backside.”

Though building a life in the “sweet spot” between the dark side and light side might be a human’s best bet, it seems that Kepler-438b is no home-sweet-home.

“For us, if we were to be airlifted in to Kepler-438b, we’d have a hard time,” Batalha says. “But you know, life is prolific, robust and creative, and I could imagine that there would be life on that planet that’s adapted just fine.”

This story is based on an interview from PRI's The Takeaway, a public radio program that invites you to be part of the American conversation. All this week, we'll be exploring distant worlds light years away from Earth in our new series, “Brave New Worlds: Looking for Life in The Goldilocks Zone.”