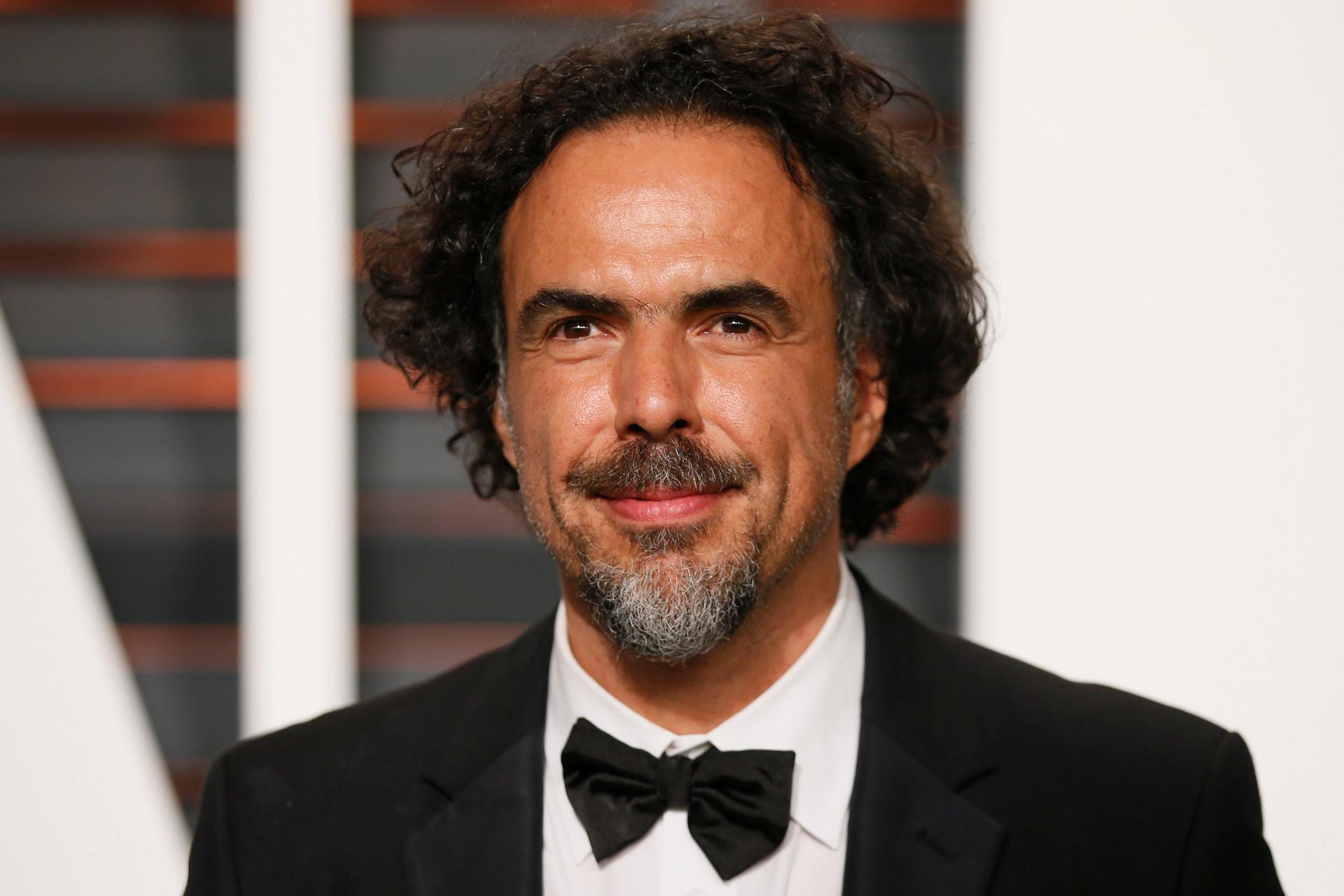

Alejandro González Iñárritu’s wins at the Oscars marked the first time the night’s two biggest awards — for Best Director and Best Film — went to a Mexican-born filmmaker.

Few shows draw a global audience like the Oscars, and Mexico City certainly took note of the awards show this year.

That's where I headed to a friend’s house to watch the 87th edition of the ceremony. We snacked, cracked jokes and then watched as Birdmanía took hold.

Mexico City-born director Alejandro González Iñárritu headed up on stage more than once to accept statues for “Birdman" — first for the Best Director award, and then for Best Picture. The film’s Mexican cinematographer, Emmanuel Lubezki, known by his nickname “Chivo” — "goat" in English — also won a second Oscar for his work on that film.

And Mexico even got in on the action for Best Documentary Short Subject: "La Parka" (“The Reaper”), a film produced in Mexico by Nicaraguan-born Gabriel Serra, earned a nomination. It was a big night in all for Mexico, where a winning streak is underway.

Iñárritu’s awards mark the first time the two biggest Oscars went to a Mexican-born filmmaker — or any Latino, for that matter — and they follow wins in 2014. That’s when Alfonso Cuarón, also born in Mexico City, won Best Director for “Gravity;" Lubezki won his first Oscar for cinematography for that film. And that's all in addition to Iñárritu’s nomination for Best Director in 2006 for “Babel” and several wins for “Pan’s Labyrinth,” directed by Mexico's Guillermo del Toro.

In Mexico, enthusiasm for the Oscar-winning group of filmmakers is clear. The local press hailed Iñárritu’s “Midas touch” and recalled how he has skyrocketed to fame from his early days as a DJ at a Mexico City radio station in the 1980s. They also noted that Cuarón began his career decades ago on the technical side of Mexican TV before launching his films, which include "Y Tu Mamá También," a classic coming-of-age film set in Mexico.

But, at film schools in Mexico City, students are plenty aware that working with big budgets or winning international acclaim is still tough. Mateo Miranda, a student at Mexico City’s Centro de Capacitación Cinematográfica, watched the Oscars and was encouraged to see so many Mexicans on stage. “It’s a good time,” Miranda said. “Obviously, when Lubezki and Iñárritu went to the stage, it was a really happy moment, like when Mexico scores a goal.”

But he added that the filmmakers’ careers now exist outside of Mexico. That fact, he said, “reflects that in this country, it’s really hard not only to get the funding to lift the project, but also to distribute it and to make a living out of it here in Mexico."

Yet one of Miranda’s classmates, Diego Noriega, jumped in and said he's determined to stay in Mexico and be a part of a generation of filmmakers who find success at home. “I would like to not leave Mexico and I want to make my films here, the films that I like and that are as commercially and critically viable as possible,” he said.

Mexico’s government does provide some financing for the small number of students who focus on film here. But that funding is still limited, and Mexico’s filmmaking community, like many others in the world, must seek out creative ways to pay for production. But that’s something Noriega and many of his fellow classmates are prepared to do, especially as they see more Mexican-born filmmakers steam ahead.