"That was the first time I went into Darfur. We had been ushered into Darfur by the rebels to see villages that had been burned. This was an actual training of new rebel recruits.''

Lynsey Addario's new book, "It's What I Do: A Photographer's Life of Love and War,'' is a memoir of one of the world's few women war photographers. Steven Spielberg will direct and Jennifer Lawrence will star in a movie about her life. Here, Addario tells us the stories behind some of the amazing images she's made.

In battle: March 2011, Libya

"There were a handful of photographers and we were on the front line and we heard a helicopter. We were just waiting to see what would happen. There was no cover — no place to hide. But there was a car. We crouched, trying to bury ourselves, under the hood of the car. There were bullets and and my fellow photographer John Moore and I were taking pictures as we could."

The Sneaker: April 2011, Libya

Addario was one of four New York Times journalists captured by Libyan soldiers and held in March 2011. "We were released from captivity on March 21, and Bryan went back two weeks later, to see where we were kidnapped and to try to find our driver's body. He recognized my shoe. It had no laces. They had used my laces to tie me up.''

Boom: March 2003, northern Iraq

"I went to northern Iraq to wait for the fall of Saddam Hussein. At the same time, US Special Forces were helping the Kurdish peshmerga. … We were covering that proxy war as troops were headed to Baghdad. That was one of the first times I'd covered this kind of war … I was trying to capture the flash that shows fighting at that moment."

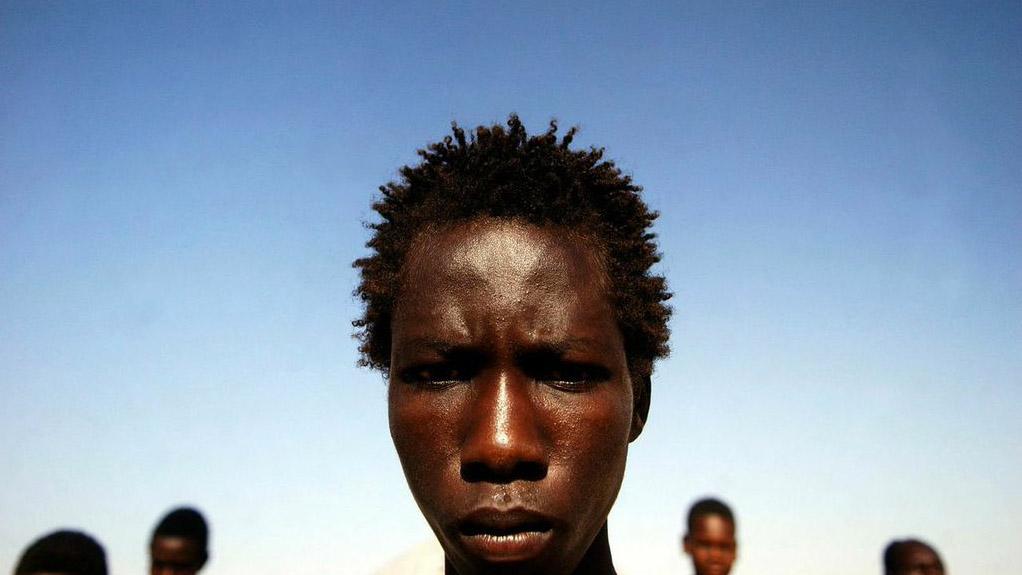

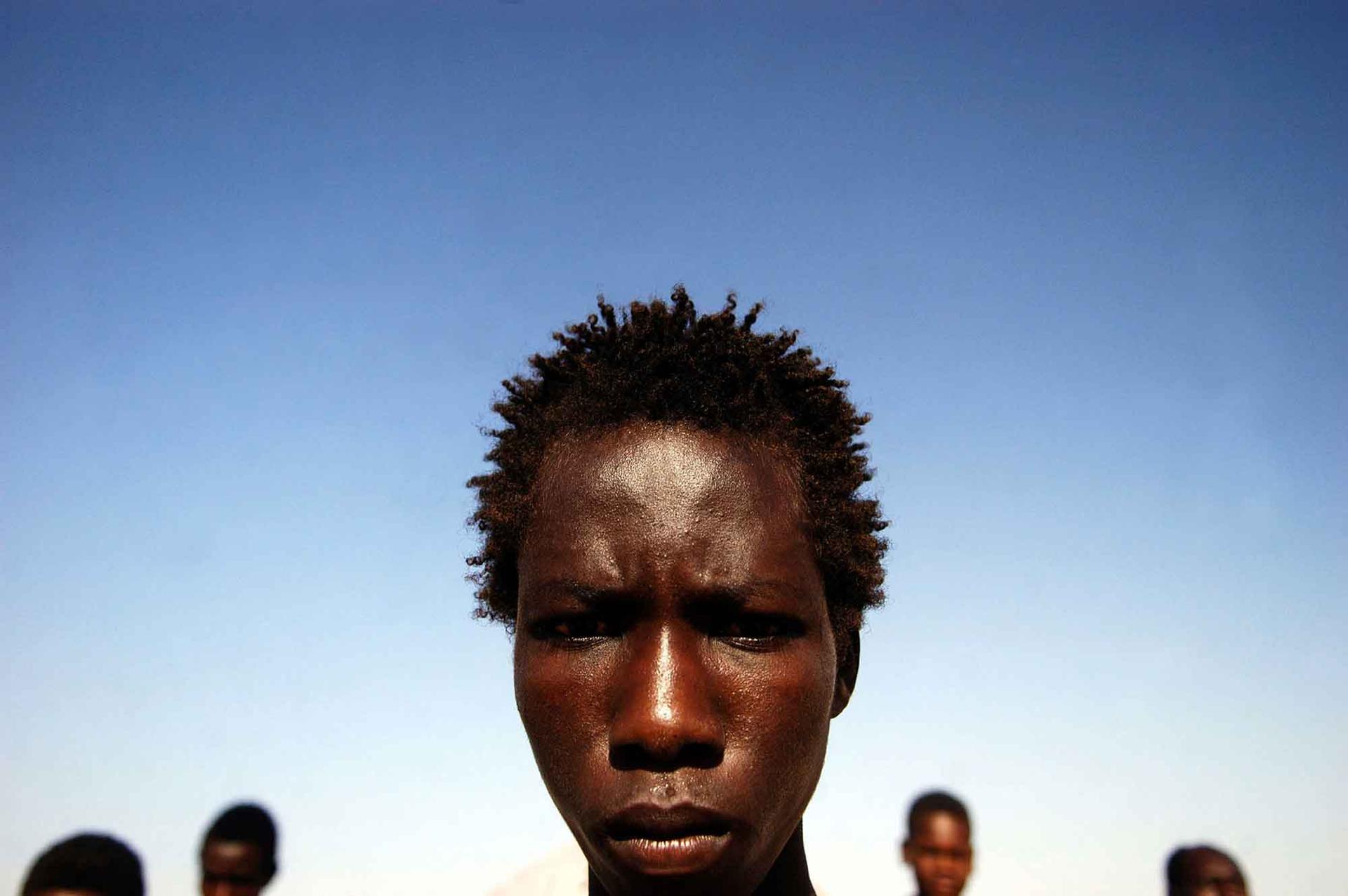

Rebel recruitment: 2004, Sudan

"That was the first time I went into Darfur. We had been ushered into Darfur by the rebels to see villages that had been burned. This was an actual training of new rebel recruits."

Vumila: 2007, Democratic Republic of the Congo

"I started covering the DRC in 2006. Lydia Polgreen and I went back in 2007. One story that we kept hearing was about women being raped in the fighting. So I went back to tell the story of women rape victims. I spent two weeks interviewing women back to back and taking portraits. With each woman I tried to take something different. With Vumila, I asked to take a picture — and she just sat there, so proud and beautiful, after telling me the most devastating story."

Bandaged boy: September 2007, Afghanistan

"In September 2007, Elizabeth Rubin and I went in to one of the most dangerous places in Afghanistan to try to figure out why so many civilians were dying … One night, there was a battle going on, and US troops were being attacked by the Taliban, and the commander made a decision to drop a bomb. When we went in the next day, a boy told us he had been injured by shrapnel from a house that had been hit next door. … Were the injuries consistent with shrapnel? The family said yes; the Army said no. This gets to the ambiguity of war. My editor (at the New York Times) pulled the photo because he said he couldn't confirm he was an injury of war.''

Special delivery: November 2005, Afghanistan

"I was working on a story of women in Afghanistan for National Geographic … Maternal mortality was a very big issue. So many women die in Afghanistan because they have no access [to medical attention] … On the way back, we saw these two women in burqas at the side of the mountain. We both noticed that something was amiss, because there were no men with them … One was in labor … We offered to take them to the hospital, but they said they needed the husband's permission." Addario and her guide, a doctor, drove to find the husband, got permission, then got the woman to the hospital, where she had her baby.

Free: March 2011, Libya

This image of Addario and fellow New York Times captives in Libya was taken after their handover to Turkish authorities in Tripoli, the Libyan capital. "We had been told that we were released and we were handed over to the Turkish government. …. We were all pretty traumatized. We didn't know what to believe. … We were handed over to the Turkish government in a very orchestrated ceremony … The Turks took us to the Turkish Embassy. They were amazing. They opened up the embassy to us. They made lunch for us. They asked if they could take a picture with us. We were still afraid, because we didn't really think we were released until we were over the border with Tunisia. … I look at the photograph, and see how blank our faces were, and wondered if people thought we were as traumatized as we felt.''

Hospital: August 2011, Somalia

"I was five months preggers at the time, and I was covering the drought at the Horn of Africa … It became very clear to me that the story was in Somalia, since so many people we were photographing were fleeing from there, and there was no medical care there. … Very shortly after I arrived in Mogadishu, I went to this hospital, and it was an apocalyptic scene. … When I saw this boy, his mom was trying to close his eyes, close his mouth. It was like a premature death ritual. And at the same time, Lukas was kicking inside of me, and I thought this was so unfair.''

The photographer

Lynsey Addario, as photographed by Kursat Bayhan.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?