A new type of diet pill could be a major breakthrough in treating obesity and a range of diseases

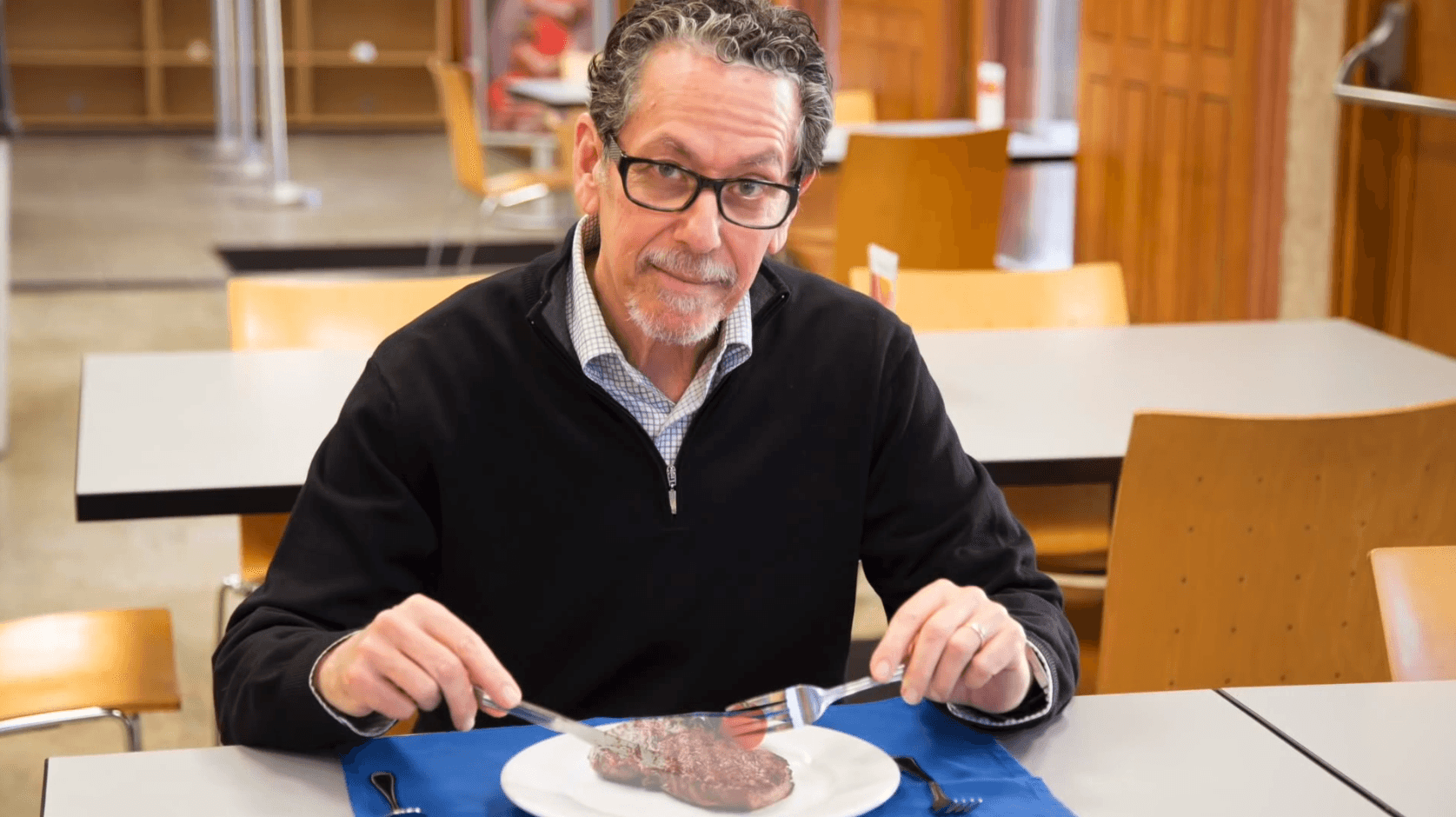

Ronald Evans, director of Salk’s Gene Expression Laboratory, has developed a compound called fexaramine that acts like an imaginary meal, tricking the body into reacting as if it has consumed calories.

With each bite you take, your body flips on a series of chemical switches that get your gastric juices moving, the bile flowing and lead your heart to pump more blood to your intestines.

Those switches also send a message to your body’s fat deposits telling them, “Get ready! We've got an incoming load of calories.” And now, researchers have figured out how to flip those switches without swallowing anything but a pill — no calories needed.

Ronald Evans, the director of Salk’s Gene Expression Laboratory, has developed a compound called fexaramine that acts like an imaginary meal and tricks the body into reacting as if it's consumed calories. Evans wrote about his research in the journal Nature Medicine.

The hope is that this new development will lead to an effective treatment for type 2 diabetes and obesity in humans. Mouse trials for obesity and diabetes showed lowered glucose and improved insulin levels, as well as weight loss.

“As soon as you begin eating a meal, your body begins to respond, because eating is the key feature of survival and you can’t wait until you finish the meal to begin processing that food,” Evans says. “It begins right away, and what we realized is that the process begins in the intestine with the release of a substance called bile acids.”

The focus of Evans’ research was to develop a pill that would mimic the body’s naturally produced bile acid. The idea was based on a 1995 discovery of a receptor — a type of molecule — in the intestine that senses bile acids.

During digestion, bile acids are released in the intestine to aid the body’s absorption of nutrients. The bigger the meal, the more bile acid that is produced and the more the receptor sensor is stimulated, Evans explains. Fexaramine fools the body into thinking it has eaten a meal.

“We build a drug that can interact with that sensor, that makes the sensor think, “Oh, you've just eaten a meal, bile acids are being produced,’” Evans says, “but that actual trigger was just our pill.”

Several diseases are linked to poor bile acid properties and liver problems. A major safety feature of fexaramine is that it does not need to be absorbed into the bloodstream, but instead stays in the intestine and passes through the body.

Because fexaramine fools the body into thinking that bile acid is flowing, it could have many uses in addition to cutting down on diabetes and obesity. The drug could be key to treating certain disorders and difficult-to-manage intestinal diseases like intestinal inflammatory disease, bile disease, inflammatory bowel disease and Crohn’s disease, Evans says.

“That's the area where we could be some benefit," he says. "Also in bile acid problems in the liver, where patients have tremendous problems often leading to liver transplant where this pathway could be very effective.”

In the mouse trials, fexaramine also increased the thermogenic response, causing the mice to lose weight by burning through stored “brown fat” to convert into body heat. In other words, the mice lost weight by shivering.

Since those trials, several new generations of derivatives of this drug have been developed and would be more appropriate for human use, Evans said, although human trials have not yet started.

This story first aired as an interview on PRI's Science Friday with Ira Flatow.