Why some people camped out all night at California DMV offices

The Granada Hills DMV location, a former Albertson's grocery store, is one of four new processing centers opened by the DMV to serve first-time applicants.

California, home to the largest number of undocumented immigrants, is now the 10th state to allow them to apply for driver's licences.

On January 2, the state's Department of Motor Vehicles offices opened their doors to thousands of these immigrants, and the lines were long. Some applicants had scheduled appointments, while others waited hours for walk-in service. By the end of opening day, the DMV reported seeing more than 17,000 applicants.

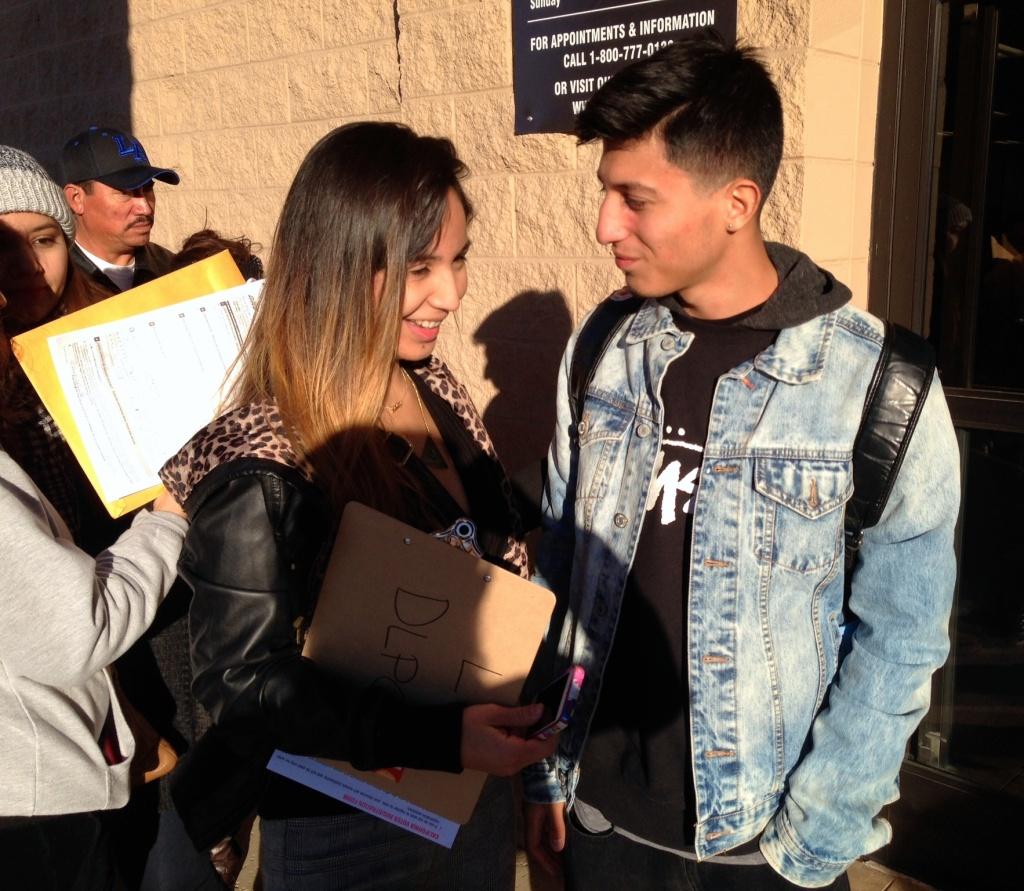

In Grenada Hills, a Los Angeles suburb, about 350 people stood in line at a DMV processing center located in a shopping center. It wrapped around the plaza before the doors opened at 8 a.m. Carlos Barrera arrived around 9 p.m. the night before to nab a spot for the first day. He says he didn't want to wait the month he'd been told it would take to get an appointment.

"When you're driving with no license it's a risk. It's like a flip of a coin," Barrera says. "You never know when they're going to stop you."

Pedro Soriano, who was first in line, slept outside the DMV in a lawn chair, while his wife, who needs the license, stayed in a heated car with their daughter.

The DMV projects some 1.4 million immigrants will seek licenses over the next three years under the law signed by Gov. Jerry Brown in 2013. To handle the extra business, the agency has hired more than 900 additional employees.

Other states that have adopted a licensing program for drivers without legal status say it's a way to improve public safety.

States that allow undocumented immigrants to apply for a driver’s license say that the newly licensed drivers are more likely to obtain auto insurance. That will be relatively affordable for new drivers: The state has created a Low Cost Auto Insurance Program for undocumented immigrants to sign up for.

Immigrants illegally living in California were allowed to get licenses until 1994. Los Angeles city council member Gil Cedillo, who led the campaign to reinstate driver's licenses for immigrants when he was in the state Legislature, arrived early in Granada Hills to welcome the first applicants.

"Every Californian will benefit," Cedillo says. "We expect a big reduction in our hit-and-runs. We expect people to be better drivers and expect to move up the ranks of safer highways."

The DMV says initial interest in the program has been strong. Nearly 400,000 appointments for 2015 were made in just two weeks in November, a 115 percent increase in activity over the same period in 2013.

DMV spokeswoman Jessica Gonzalez credited the spike to applicants newly authorized by the bill. But it's not clear whether demand for the program will stay steady, or drop off.

"We hear it's a mixed bag," Gonzalez says. "Some people are like, 'We want to get in right away.' And some people are a little bit more cautious."

Some immigrant rights' advocates have expressed concern about AB 60 applicants handing over personal information to the government, especially if they've had run-ins with immigration authorities.

Still other advocacy groups have pushed hard to get licenses into the hands of immigrant drivers and pressured the DMV to issue a design that would avoid stigmatizing cardholders. After months of back-and-forth with the Department of Homeland Security, the DMV finalized a design that included the letters "DP" for "driving privilege" on the front of the card to distinguish it from a standard driver's license. Also included is wording that the card cannot be used for "official federal purposes."

Critics of the law, such as Californians for Population Stabilization, say it's not fair to reward immigrants in the country illegally with licenses, and question whether roads would become safer. Spokesman Joe Guzzardi predicts citizens and legal residents in California will be hurt economically.

Immigrants with their new licenses "are going to be able to drive to job sites, possibly offering to do those jobs at a lower rate of pay than the existing worker," Guzzardi says.

The agency is taking applications at all 170 of its field offices, but has opened four new "processing centers" that will only handle first-time applicants, a group that includes immigrant drivers and teenagers. Gonzalez says the centers are two to three times larger than field offices — the Granada Hills location is a former Albertson's grocery store — and are the only sites that will take walk-ins from new applicants.

Those showing up for appointments must submit documents proving their identity and California residency and take vision and driving knowledge exams.

Those who pass those exams will get a permit to practice driving so they can take a road test at a later date.

"Make sure you study," Gonzalez tells applicants. "We learned in other states that people weren't prepared to take the [written] test and the failure rate was very high."

Most of the applicants at the Granada Hills location were Spanish speakers. But there were also immigrants from Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

"It's amazing. It's going to change my life," says Bar Mandalevy, a 26-year-old Israeli, who lives in LA's Westwood Village. He says he has been driving without a California license for five years. As a jewelry maker, he travels as far as San Francisco to sell his wares at street fairs.

"I just drive with my foreign license, and drive slow," Mandalevy says. "It's a very nerve-wracking experience everywhere I go."

A version of this story was first published on KPCC's Multi-American blog. Read the original story here.