Despite protests, Ontario is going forward with a newer, more modern sex ed curriculum. These girls helped make it happen.

Tessa Hill and Lia Valente helped get the issue of consent into Ontario's new sex-ed curriculum.

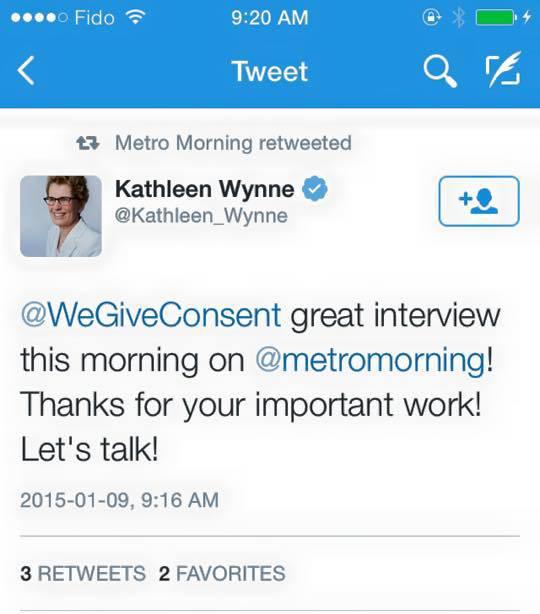

There’s a battle afoot over sex education in the Canadian province of Ontario. The government says it’s overhauling its sex ed curriculum — which it hasn’t done since 1998 — to prepare kids for issues like tolerance and consent. Some parents say they’ll pull their children out of class rather than expose them to what they call harmful material. But two teen activists are not only welcoming the changes: they helped make them.

A little background: starting in the fall of 2015, the new sex ed lesson plans will start in Grade One with “identifying body parts, including genitalia.” With each successive grade, the curriculum encourages more knowledge about sexuality, in a way that the government says is age and developmentally appropriate. But it didn’t emphasize the issue of consent enough for 13-year-old students Lia Valente and Tessa Hill.

The two eighth graders, for a class assignment, made a short film that deals frankly with rape, including cases like the sexual assault of a high school girl in Steubenville, Ohio.

“I think the new curriculum is really awesome,” Hill says. “Both Lia and I are really happy it’s been updated.”

Valente adds: “I’m mostly just happy that the curriculum is finally going to catch up with what teens and young people have already been learning through the media, [since] that may not be healthy or reliable information.”

But what Valente calls reliable, others call inappropriate.

Thousands of Ontario parents kept their children out of school in recent protests against the new curriculum.

More than 2,000 people gathered recently on the lawns of the provincial legislature in Toronto. Many of the protestors wore signs of religious faith, from hijabs to rosaries, and many had concerns about content of lesson plans aimed at the youngest students. A 10-year-old named Manahil addressed the crowd, saying that first through third grades are “the time for kids to play and learn science, math, social studies and English. Not sex, the dirty stuff that will be taught at school.

“I’m opposed to this because in the future, I don’t want to teach my kids anything ‘inappropriate,’” says 21-year-old Esther Henen. “In my definition, ‘inappropriate’ is anything exposing different parts, private parts, to the opposite gender.” Henen admitted she had not yet had time to read the proposed curriculum.

Threaded through the protests are suggestions that the debate over sex education is also for some a debate about homosexuality. One speaker asked to be “protected” from the purported homosexual agenda of Premier Wynne, Canada’s first openly gay premier.

Away from the arguments and the protests, Lia Valente and Tessa Hill are trying to spread the word about consent by showing their film online and at meetings. For them, a new approach to sex education means children won’t learn about sex solely from Internet porn or be unprepared for social media issues like sexting and body-shaming.

The girls know they’re growing up in a different world than their mothers did. Valente says her mother told her she didn’t know what “consent” meant “until she was in her 30s.”

The two are not daunted by the generational gap; they’re excited to tackle it.

“I am definitely going to grow up differently because of what I’ve learned…about sex in general, and gender and sexuality,” Hill says. “I know I can be comfortable in myself and also just be confident.”

Her province is trying to do the same.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?