Turks can’t read much of their own history, but the drive to change that isn’t popular with everyone

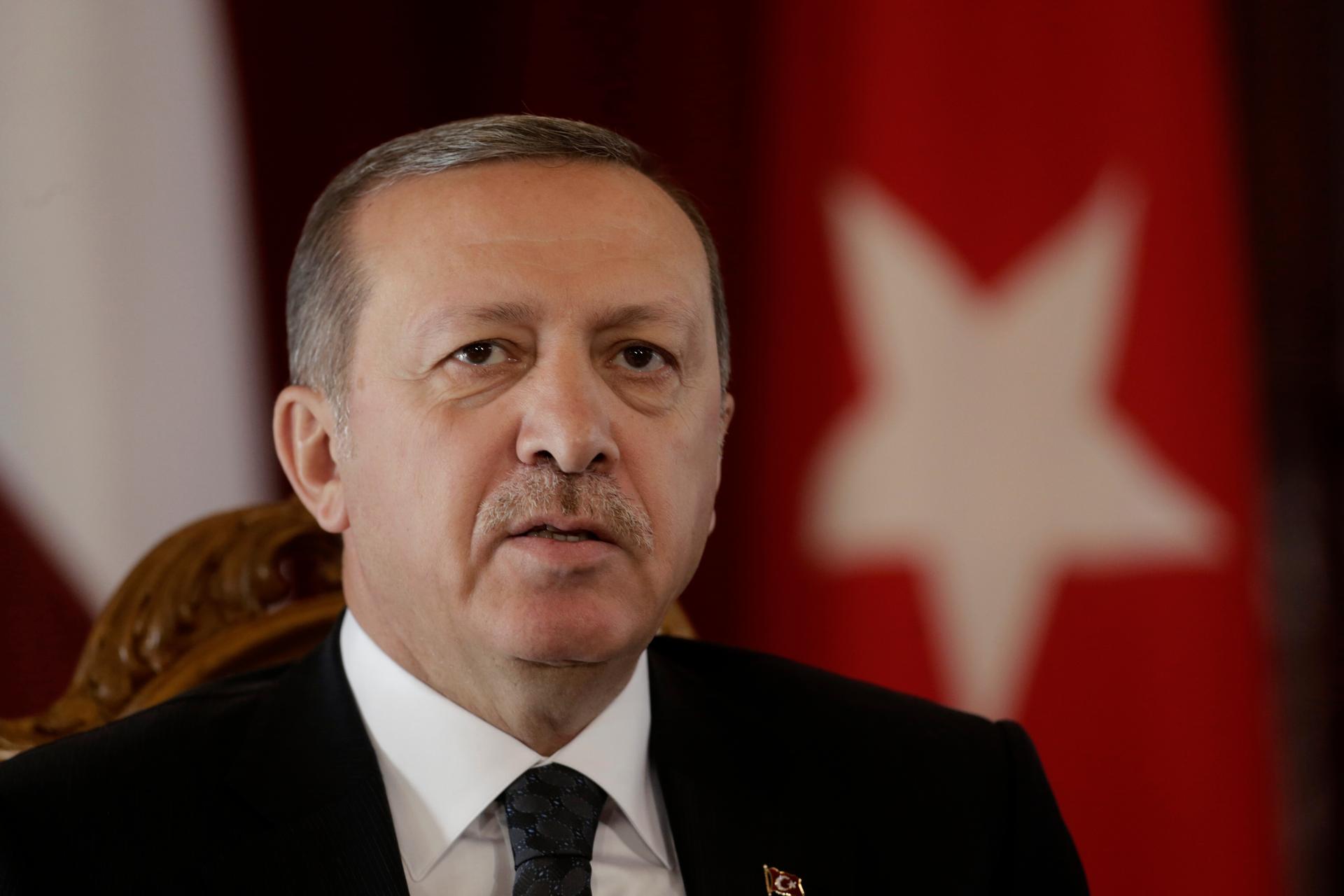

Turkey's president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, speaks during a news conference in Riga, Latvia, on October 23, 2014.

“Our children will learn Ottoman whether they like it or not!”

Turkey's president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, recently put students on notice with that declaration. It's the latest in a long line of pronouncements that Erdogan's critics say are evidence the president is becoming more and more anti-democratic — even authoritarian.

But looking back to Ottoman rule could play well, as I discovered during a visit to the lengendary Eyup Mosque. The area is scattered with burial grounds, with a massive cemetery snaking up the hill that overlooks the mosque. Famous Ottoman sultans and pashas are laid to rest here.

“I wish I could read these tombstones," says a man name Mustafa, pointing to the tomb of one former pasha. “Look there. I don’t know what happened there. I don’t know what this person’s history is.”

That's because, during the six centuries of the Ottoman Empire, laws, religious texts and literature were written in Arabic script, using a mix of Arabic, Persian and Turkish words — that's "Ottoman Turkish."

But Kemal Atatürk, the founder of modern Turkey, banned all of that. Turkish is now written in Latin script, and much of the vocabulary is vastly different than the words used in Ottoman times, either resurrected from the history of Turkic languages or borrowed from Western ones.

Erdoğan argues that Turks should be able to read their own history, an idea that resonates for Mustafa — and for me, too. My own ancestor is buried in Eyup, and I cannot read his gravestone, either.

But, like everything in Turkey, the push to teach Ottoman is also laden with politics. The language is most often associated with Islam — the cornerstone of the Ottoman Empire — and with what some say is Erdoğan's obsession to push religion on today’s citizens.

Mustafa doesn’t see it that way. “Ottoman should be my first language, my mother tongue,” he says. For him, it’s not about religion — it’s about his heritage. Ottoman should be his mother tongue.

Others aren't buying it. "For some people, reading gravestones is important, for history it is important, but it shouldn't be required,” says 17-year-old Fatih Seven. He's a high school senior, so the proposal for mandatory Ottoman instruction wouldn't affect him. Still, he’s concerned.

“It's not important, because people in Turkey even can't talk English,” Fatih says, apologizing for his own broken English. He wishes Turkey’s leaders cared as much about the languages of today, languages that would help him get ahead in the world, instead of worrying so much about the past.