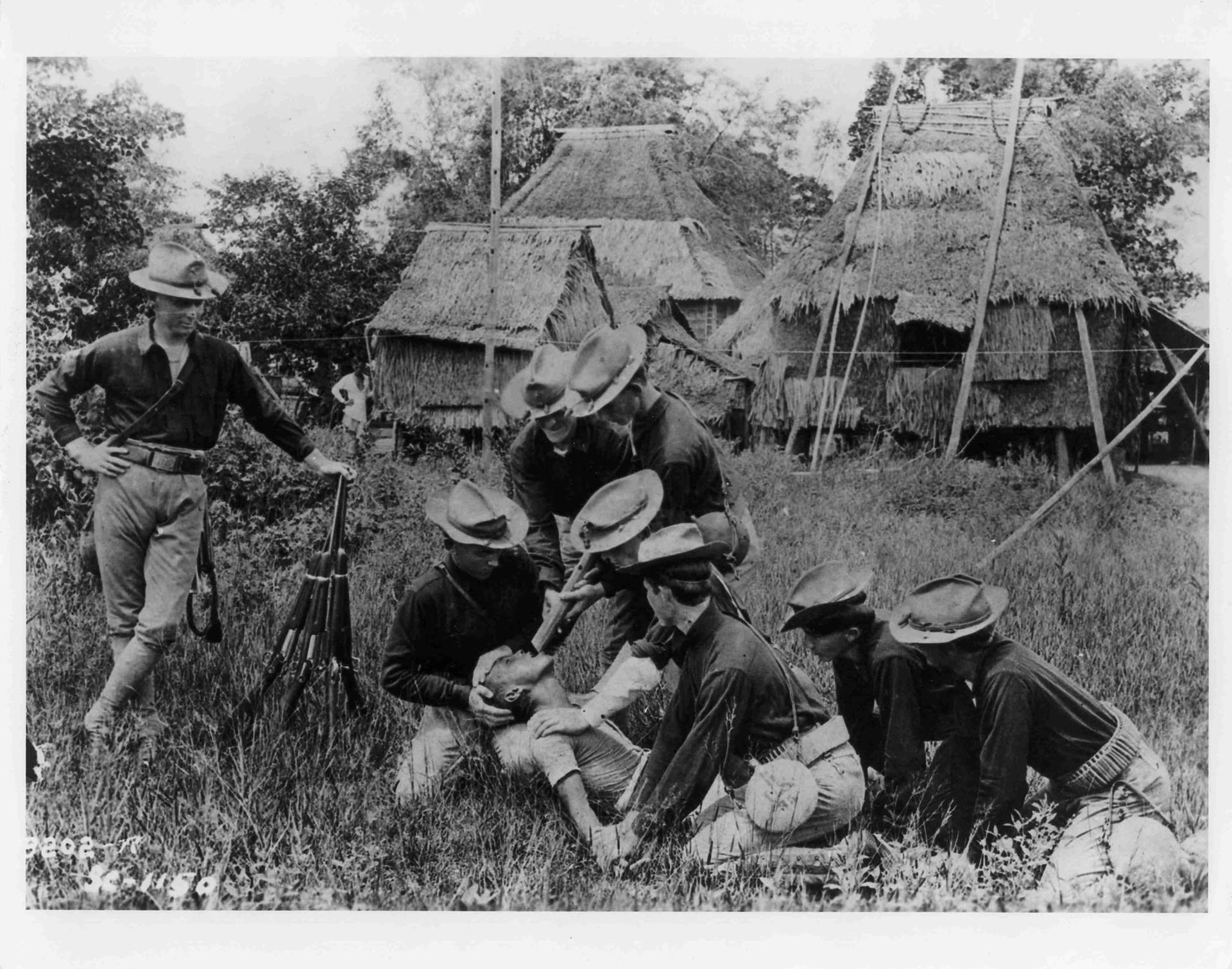

Soldiers from the 35th US Volunteer Infantry subject a Filipino to the ‘water cure,’ a common ‘enhanced interrogation’ technique employed during the war to pacify the Philippines between 1899 and 1902.

Waterboarding is essentially a method to make people feel like they are drowning. It is a terrifying way to force people into doing or saying whatever you want. And it's been around for a long time.

The first documented use was during the Spanish Inquisition — and it was as reviled then as it is now.

Its use was also documented almost 400 years ago in the East Indies, when it was perpetrated by the Dutch on some English traders who were trying to set up shop on Dutch turf. The so-called Amboina Massacre of 1623 was widely publicized in England at the time, and water torture was fiercely denounced as a barbarity, even in that savage age.

Senator John McCain reminded us this week that the United States hanged Japanese officers after World War II for torturing prisoners of war. Professor Gregory Urwin of Temple University cites the example of Isamu Ishihara, the former chief interpreter at the Shanghai POW Camp. Ishihara was sentenced to life in prison with hard labor by an American military commission after being found guilty of committing "cruel, inhuman and brutal atrocities against certain American prisoners of war."

Chase Nielsen was one victim of the Japanese. He was an aviator who took part in the famous Doolittle Raid in 1942, the first US strike against the Japanese mainland. The Japanese public was enraged by the raid and Nielsen was tortured as a result. He survived.

The Nazi German secret police, the Gestapo, also used water torture. The Communists used it on US POWs during the Korean War. And it was commonplace in Cambodia during the brutal rule of Pol Pot in the 1970s.

The United States stridently denounced all those incidents as crimes. What’s less well-known is that the United States itself has a relatively long and deep relationship with this form of torture.

During the Spanish-American War of 1898, the United States occupied the Spanish colony of the Philippines. When the Americans wouldn’t leave, the Filipinos launched a violent insurgency. US troops responded with severity and used torture to interrogate suspects for information. One method was the "water cure."

That worked differently than waterboarding. The perpetrator would shove a funnel into the victim's mouth and then fill him with water until his stomach distended. Then he would jump on the victim's stomach until he vomited.

However, that was not a policy approved at a high level and President Teddy Roosevelt was furious when he found out. At least one US army officer was court martialed, and a general was thrown out of the army for condoning the practice.

However, in a sense, the water cure was just an extension of law enforcement practices back in the US.

The shocking truth is that police forces across the country would commonly give suspects the third degree to try to get confessions out of them. The water cure was one of the tools in that arsenal.

In 1910, US courts began throwing out confessions that had been obviously forced out of defendants, especially when defendents appeared in court still sporting bruises or broken teeth. That made the water cure more common, because simulated drowning left no marks on the body.

The full extent of the abuse was exposed by a commission of inquiry appointed by President Herbert Hoover and led by former attorney general George Wickersham. Hoover appointed the commission to learn why the enforcement of alcohol prohibition was failing so badly. Wickersham took his assignment as an opportunity to lead a comprehensive review of law enforcement practices.

One of his reports, published in 1931, was the Report on Lawlessness in Law Enforcement. It found that "the inflicting of pain, physical or mental, to extract confessions or statements … is widespread throughout the country."

Psychologist G. Daniel Lassiter examined the report in detail for his 2004 book, Orchestrated Physical Abuse. He described police use of the water cure as a "modern day variation of the method of water torture that was popular during the Middle Ages."

He wrote that "the water cure consisted of holding a suspect's head in water until he almost drowned; or thrusting a water hose into his mouth or down his mouth; or forcing a suspect to lay on his back (if not already strapped to a cot or slab) while pouring water into his nostirils, sometimes from a dipper until he was nearly strangled."

Outrage at the findings of the Wickersham Commission led to police forces trying to rein in this kind of behaviour. But it’s believed to have persisted into the 1940s.