This nonprofit group is trying to make the world more equal — through mapping

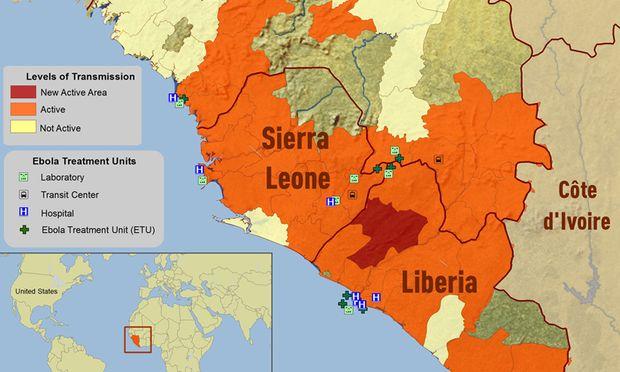

This map show the distribution of the Ebola virus epidemic in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone as of October 2014.

Maps give us incredible insights into the world around us. Many of us turn to Google Maps and see most of what we need to know — everything from rivers and mountains to roads and cities.

But in poorer parts of the world, poverty exists not just in terms of money, but in terms of data. Towns and cities are often absent from maps. Miles of landscape aren't tracked in a reliable way. And that lack of data feeds the cycle of poverty, making aid efforts a challenge, and making communities less aware of where they stand.

Dave Imus knows the art and science of creating truly usable maps. He is a mapmaker who's credited with creating the greatest and most detailed US map ever made.

Dale Kunce, a senior geospatial engineer at the American Red Cross, is the US lead for the Missing Maps project, aims to plot complete data on streets, rivers and other geographical features around the world, with the help of a global network of volunteers. They ultimately hope to help improve the response of humanitarian groups.

He says he's already seeing a difference in the figurative and literal landscape.

“In the last eight months, we’ve worked really hard to put major cities of Freetown, [Sierra Leone,] and Monrovia, [Liberia,] on the map,” Kunce says. “They’re cities that, if you were to go look at in Google Maps, Bing Maps or Open Street Maps before the Ebola outbreak, they were basically blank — there was no information about these places.”

In the months since the Ebola outbreak, Kunce says almost 3,000 volunteers with the Missing Maps project have made about 13 million edits to map streets, rivers, buildings and more.

“They’ve built out the fabric of these cities,” says Kunce “It’s all of that important information that allows you to get an understanding of the geographic place, which allows us to fight Ebola a little bit better. We see towns that we didn’t know existed two weeks ago.”

By mapping cities and smaller towns in Ebola-stricken nations, Kunce says that medical professionals can better combat the outbreak by knowing the exact origins of new infections. Though Google and its mapping system is incredibly powerful, Imus says that they don’t serve the globe’s most vulnerable sectors.

“I accept Google maps for what they are — they’re geared towards people with money in their pocket who are travelling or looking for real estate,” he says. “I get frustrated at times with maps of that genre because I like to stray outside of the places that have shopping malls, where their coverage really drops off rapidly.”

Kunce says literally putting places on the map can help instill a deep sense of pride in local communities that have historically been excluded from global geography systems.

“I think it has a huge psychological effect,” he says. “[Missing Maps] wants to instill that pride. And we want to be able to get the community to sort of build the map themselves so that the data is free and open for anyone to use.”

Empowering people with knowledge of their surroundings can have deep effects. If a community in Eritrea wants a new school, for example, Kunce says awareness of land and road systems and the surrounding physical context will allow them to better advocate for themselves.

But empowering communities in the developing world is easier said than done.

“In the places that we work, they’re not as data-rich as the United States” Kunce says.

This story first aired as an interview on The Takeaway, a public radio program that invites you to be part of the American conversation.