How to walk on ice, and other essential winter-survival tips for newcomers to America

Elizabeth Ross, in red scarf) and Ghay Hu, in tan pants, give pointers to ethnic Karen newcomers from a Thai refugee camp on how to tread across the ice in a St. Paul parking lot. Ross and Hu teach cultural orientation classes at the International Institute of Minnesota, one of the state’s resettlement agencies.

Until recently, Ehsher Mu has lived his entire 24 years in a Thai refugee camp. Last month, he boarded a plane to Minnesota, wearing flip-flops suited for the only climate he's ever known.

A day later, he remained sockless in frigid, toe-curling temperatures while attending a winter-survival class in his new home of St. Paul. Resettlement workers offered him snow boots and cold-weather tips, but Mu remained anxious about getting through the first real winter of his life.

"I'm worried," he said in his native Karen language. "I never saw this kind of weather."

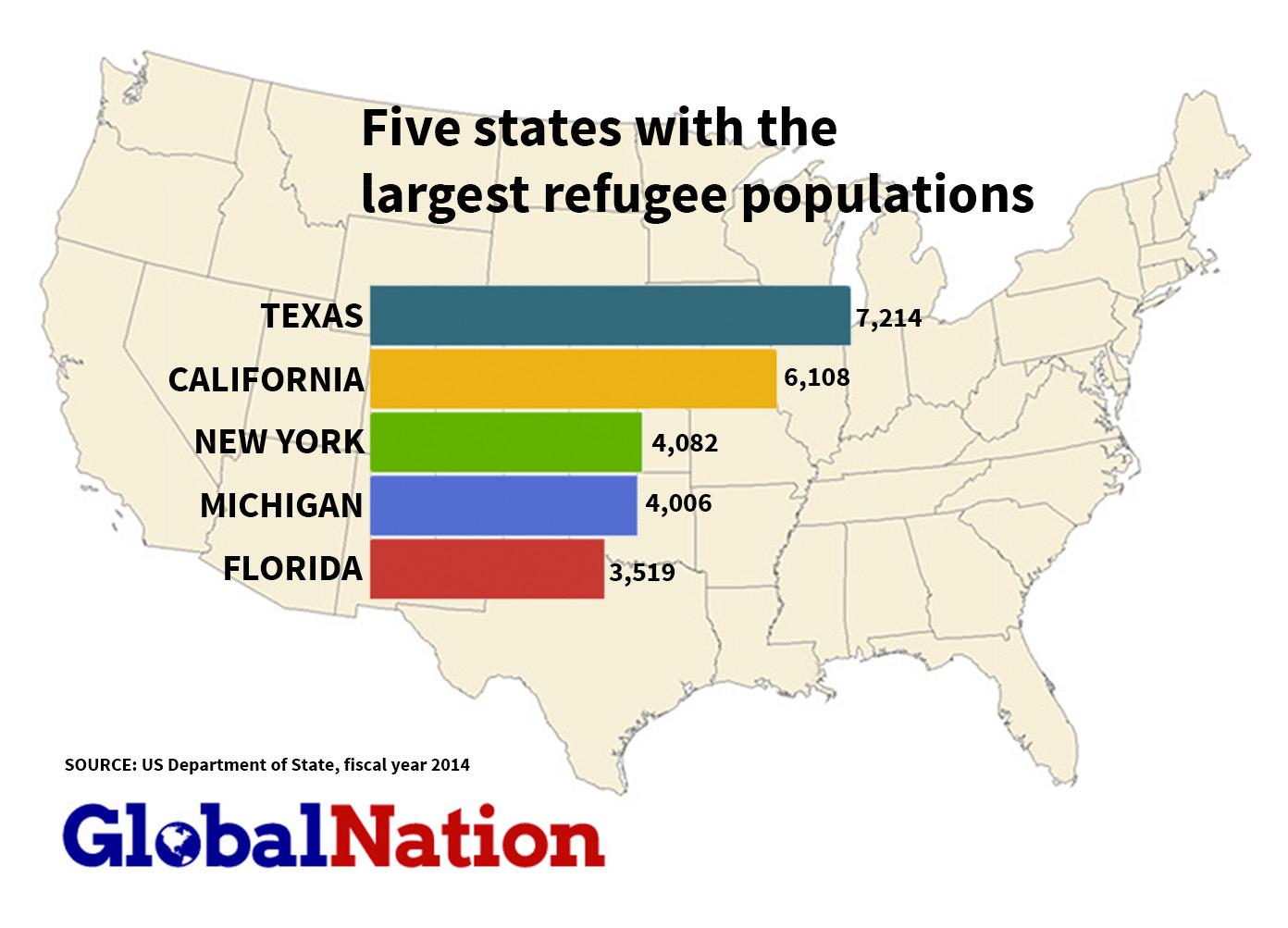

Every year, the United States welcomes tens of thousands of refugees from all over the world. Many of those refugees are from warm climates and they wind up seeking a better life in one the coldest states in the country.

With a ruthless winter already under way, the latest arrivals in Minnesota are learning to survive the Arctic sting. Lessons on how to bundle up and use a thermostat are part of a cultural orientation offered by the International Institute of Minnesota, which helps resettle refugees.

The institute's Liz Ross, who leads the training, clicks through a slideshow with pictures of mittens and boots. More than a dozen new refugees, most of them ethnic Karen from Myanmar, watch with bemused faces as Ross encourages them to make snow angels and try ice skating.

Adapting to winter will be a huge part of their integration in a state that prides itself on bad-weather hardiness. But the adjustment can be tough, said Ghay Hu, a case manager who arrived as a Karen refugee in 2009.

"The first year will be difficult," Hu said. "To go to school, to find a job, you have to struggle in the snow. The kids are happy, but for the adults, it's really hard."

The newcomers trade smiles, mentioning the runny noses, numb fingers and headaches they've experienced in their new climate. Some faces recoil at one slide on the screen: a picture of a man whose swollen hands look like purple fingerling potatoes.

"This is what frostbite looks like," Ross said. "It's ugly."

With that cautionary tale, Ross and Hu take the newcomers outside, onto a large frozen patch in the center's parking lot. They learn an essential Minnesota skill: how to tread cautiously across the ice.

Ross tells them to look down, while walking slowly and carefully. She warns them not to break their fall with their hands, which can cause them to injure their wrists or arms. Instead, she advises them, to land on their bottoms.

In howling wind, the newcomers gingerly shuffle across the ice, many of them wearing donated snow boots and winter coats they received from the center. The ice is treacherous.

But even though it's a Minnesota pastime to complain about the weather, no one grumbles.

Kyig Nywe Stu grins while sporting his new, prized possession, a gently worn wool coat.

"I'm happy," he said, "and cold."

Lessons from Somali Americans

About 2,000 refugees arrive in Minnesota every year. Newcomers from Somalia have been landing in the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood of Minneapolis in large numbers since civil war erupted in their homeland in the early 1990s.

At the bustling Brian Coyle community center, Mohamud Noor, director of the Confederation of Somali Community in Minnesota, recently visited Janet Curiel's English-language class for Somali and Oromo students from East Africa.

Curiel, tapping at a whiteboard with a stick, has just taught them how to ask a useful conversation starter.

"When did you come to the United States?" the students query Noor in unison.

"I came here 15 years ago," replied Noor, who helps Somalis integrate.

The students gasp, impressed.

Noor remembers a magical moment for a newcomer from Africa — opening his mouth to taste the first snowflakes he'd ever seen. But in East Africa, he said, nothing prepared him for the concept of bitter, subzero temperatures.

"That psychological mentality is not there," he said. "You hear about it. Until you experience it, nobody can tell you what it is."

Once in Minnesota, Somali women learn to wear multiple layers of leggings beneath their loose-flowing dresses. Noor's colleague, Bosteya Jama, shared another tip:

"Double socks," she said with a laugh. "In Africa, we don't have those thick socks, so they have to wear two or three of them."

When Mohamed Duale, another Somali refugee, moved to Minnesota from Florida, the cold didn't bother him. But the thought of driving in the snow was terrifying. He remembers hearing warnings that braking too hard on the ice would cause his car to roll over.

Duale took those words to heart by driving ever so slowly — and avoiding the brakes entirely.

"I was so scared. I took all this advice from all these people," he said. "I almost hit the other cars."

His friend, Abdirahman Mukhtar, said most Somali refugees learn by experience how to survive the winters.

But for the uninitiated, local Somali-American journalists have produced videos of Minnesota snowstorms. The videos, found on YouTube and narrated in Somali, flash images of giant snowplows clearing the highways, or of Somali residents digging out their cars.

The clips are intended to shatter some myths held by their compatriots in the homeland, said Mukhtar, a community engagement coordinator.

"Most people think when you go to America, it's a rich country, the money is laying on the ground, and you can easily be rich quickly," he said. "But they never think of the other struggles or challenges we deal with, whether it's the weather, the language, the unemployment."

Despite those hardships, thousands of new refugees call Minnesota home every year. And freshly armed with ice scrapers and parkas, they're becoming Minnesotan, one careful step at a time.

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)