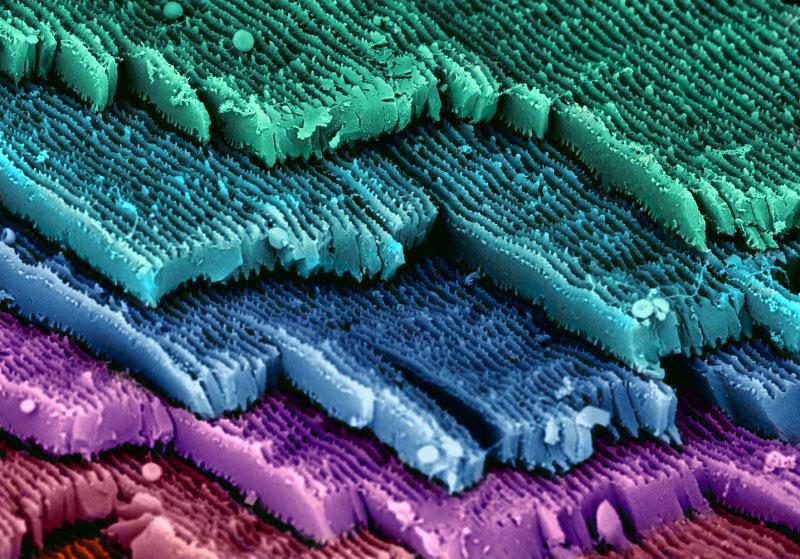

Louise Hughes, who works as biological electron microscopist at Oxford, added colors and lighting effects digitally to this image of a dehydrated “true bug specimen.”

The invention of the electron microscope in the 1930s radically changed how we see and understand the world.

A hydrothermal worm, just half a millimeter long, becomes a creature out of Star Wars. Zoom out from an underwater tropical tree and you’ll find it’s actually a human hair, seen at a resolution of one billionth of a meter.

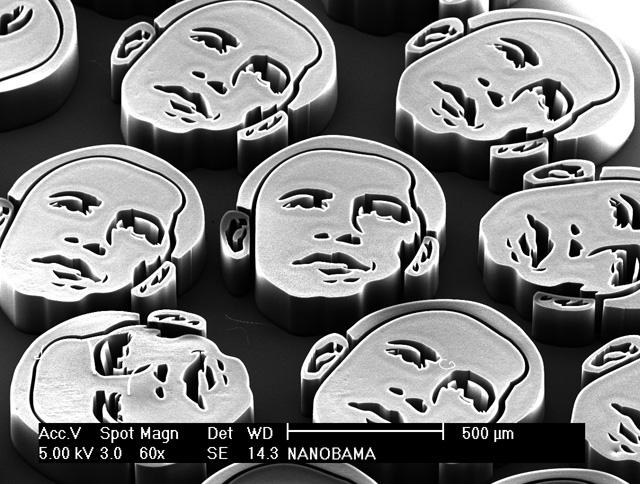

Now, with new technology developed over the past decade, a number of scientists — or part-scientists, part-artists — are not only observing the atomic landscape but shaping it, creating miniscule sculptures and other works known as NanoArt.

Cris Orfescu, a scientist in Southern California, wants to make sure you don’t call his NanoArt “pictures;" you can’t use a lens and aperture to take photos at this scale. Instead, electron microscopes use electromagnets to zap their subjects with fast-moving electrons, which can reveal the atomic world that light can't penetrate.

Images from electron microscopes have a distinct 3D negative style that gives the landscape a ghostly fuzz. The images are also black and white, but many artist-scientists add layers of color and then print the images onto canvas or fine art paper.

Those nano-landscapse can sculpted through a chemical process, as well as other means. John Hart, a professor of engineering at the University of Michigan, uses a laser to cut patterns like his "Nanobama," from 2008. To the naked eye, it looks like a tiny dot. Through the microscope, though…

Orfescu curated 60 works from around the world for the third international festival of NanoArt in Romania, which ended Sunday. Orfescu says “NanoArt could be for the 21st century what photography was for the 20th Century.” He hopes the festival will create public awareness of the technology, which to date has mostly attracted attention from the military.

But he has a simpler agenda too: Getting people to realize that nanotechnology is awesome.

This story is from Sideshow, a new podcast from PRI's SoundWorks network hosted by Sean Rameswaram that looks at the intersection of culture and technology.