India’s new leader favors the Hindi language, which is a problem for the country’s 50 million Urdu speakers

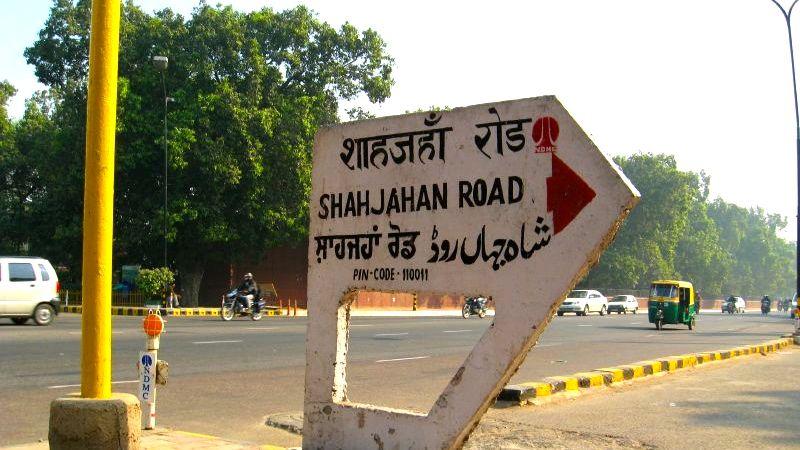

Indian street sign in four languages: Hindi, English, Punjabi and Urdu.

I spent several months in Lucknow, India, studying Urdu.

I knew that it would be a daunting task. But I had a leg up — it wasn’t going to be completely new. Several years ago, I’d studied Hindi, which the native tongue of about 25 percent of Indians. The country’s new prime minister, Narendra Modi, appears to favor Hindi, which has alarmed speakers of India’s many other languages.

To the untrained ear, Hindi and Urdu sound similar. They share a lot of the same vocabulary. But they use different scripts. And they have different connotations.

In India, Urdu is generally associated with the Muslim population.

“I come from a Muslim family, and since we were kids, we were supposed to read Urdu,” said 21-year-old Nusrat Ansari.

I met her in Lucknow, when she was auditioning to perform Dastangoi, an ancient Urdu storytelling art that’s being revived. She said that as a child, she spoke mostly Hindi.

I met her in Lucknow, when she was auditioning to perform Dastangoi, an ancient Urdu storytelling art that’s being revived. She said that as a child, she spoke mostly Hindi.

“At that point in time I wasn’t that interested in Urdu, so I didn’t take it up properly. But once I went to college and I had a bit of cultural thing,” said Ansari. “I thought, okay, I should learn Urdu,” Nusrat said.

“What do you mean by ‘cultural thing?’”I asked her.

“I started engaging in all sorts of … cultural revivalism activities.”

Hindi and Urdu are so similar that when Ansari was listening to the lines she had to memorize — which were in Urdu — she wrote them down in the Hindi script. Similarly, when I started learning Urdu, I also started out by writing in Hindi.

Writer and performer Mahmood Farooqui, who has been reviving Urdu storytelling, says reciting Urdu is a sign of prestige in India.

“Our radio anchors like to use Urdu, our television anchors like to use Urdu, parliamentarians like to use Urdu poetry, political leaders — even Modi recites a couplet or two,” he said.

But you won’t find India’s new prime minister giving a speech in Urdu. Because he’s such a staunch advocate of Hindi, many people are wondering whether his new language policies are part of a larger plan to wean out languages like Urdu.

Urdu’s origins are different from that of Hindi’s: Hindi’s script stems from Sanskrit, while Urdu traces its roots to Persian. It came into being in India around the 15th century, when Persian began to mix with local north Indian dialects. And by the 18th century, Urdu was an important literary language in India.

“It’s like English is now, in the sense that it was the language of prestige,” said Mehr Farooqi, a South Asian languages scholar at the University of Virginia. “It was considered to be the language of educated people. So everybody studied Urdu, and therefore they spoke Urdu.”

But about a 100 years ago, Urdu started to decline in India. The British wanted a common language for the country, and more and more people wanted Hindi to be that language. Hindi and Urdu — even though they were so similar in spoken form — became symbols of religious difference.

“It became like Urdu equals Muslim, Hindi equals Hindu,” said Mehr Farooqi.

This is why the new government’s promotion of Hindi is so controversial. It puts a spotlight on India’s postcolonial division into India and Pakistan. And it was another setback for Urdu, said storytelling artist Mahmood Farooqui.

“You had a lot of Hindu nationalists and Hindu fundamentalists saying Urdu created Pakistan, so let’s ban it, said Farooqui. “There was a lot of discrimination against it in schools, the government did nothing to propagate it, or to help its cause. And that continues to be the state of affairs today.”

And while some people, like Nusrat Ansari, are motivated to learn Urdu, she admits the language is struggling.

“I have met a lot of people who are really interested in this language and who would like to learn it,” she said. “But I wouldn’t say that it’s very popular and everybody understands it. Most people haven’t been that exposed to it.”

This exposure will be harder to come by if the new Hindu nationalist government keeps favoring Hindi over India’s other languages. That would only compound the problems Urdu's already facing. But there are about 50 million native Urdu speakers in India — and others, like Ansari, who are rediscovering the language through its cultural heritage. So while Urdu may not have the same dominance in India it once did, it looks like there might still be a place for it in the country.

The World in Words podcast is on Facebook and iTunes.

I spent several months in Lucknow, India, studying Urdu.

I knew that it would be a daunting task. But I had a leg up — it wasn’t going to be completely new. Several years ago, I’d studied Hindi, which the native tongue of about 25 percent of Indians. The country’s new prime minister, Narendra Modi, appears to favor Hindi, which has alarmed speakers of India’s many other languages.

To the untrained ear, Hindi and Urdu sound similar. They share a lot of the same vocabulary. But they use different scripts. And they have different connotations.

In India, Urdu is generally associated with the Muslim population.

“I come from a Muslim family, and since we were kids, we were supposed to read Urdu,” said 21-year-old Nusrat Ansari.

I met her in Lucknow, when she was auditioning to perform Dastangoi, an ancient Urdu storytelling art that’s being revived. She said that as a child, she spoke mostly Hindi.

I met her in Lucknow, when she was auditioning to perform Dastangoi, an ancient Urdu storytelling art that’s being revived. She said that as a child, she spoke mostly Hindi.

“At that point in time I wasn’t that interested in Urdu, so I didn’t take it up properly. But once I went to college and I had a bit of cultural thing,” said Ansari. “I thought, okay, I should learn Urdu,” Nusrat said.

“What do you mean by ‘cultural thing?’”I asked her.

“I started engaging in all sorts of … cultural revivalism activities.”

Hindi and Urdu are so similar that when Ansari was listening to the lines she had to memorize — which were in Urdu — she wrote them down in the Hindi script. Similarly, when I started learning Urdu, I also started out by writing in Hindi.

Writer and performer Mahmood Farooqui, who has been reviving Urdu storytelling, says reciting Urdu is a sign of prestige in India.

“Our radio anchors like to use Urdu, our television anchors like to use Urdu, parliamentarians like to use Urdu poetry, political leaders — even Modi recites a couplet or two,” he said.

But you won’t find India’s new prime minister giving a speech in Urdu. Because he’s such a staunch advocate of Hindi, many people are wondering whether his new language policies are part of a larger plan to wean out languages like Urdu.

Urdu’s origins are different from that of Hindi’s: Hindi’s script stems from Sanskrit, while Urdu traces its roots to Persian. It came into being in India around the 15th century, when Persian began to mix with local north Indian dialects. And by the 18th century, Urdu was an important literary language in India.

“It’s like English is now, in the sense that it was the language of prestige,” said Mehr Farooqi, a South Asian languages scholar at the University of Virginia. “It was considered to be the language of educated people. So everybody studied Urdu, and therefore they spoke Urdu.”

But about a 100 years ago, Urdu started to decline in India. The British wanted a common language for the country, and more and more people wanted Hindi to be that language. Hindi and Urdu — even though they were so similar in spoken form — became symbols of religious difference.

“It became like Urdu equals Muslim, Hindi equals Hindu,” said Mehr Farooqi.

This is why the new government’s promotion of Hindi is so controversial. It puts a spotlight on India’s postcolonial division into India and Pakistan. And it was another setback for Urdu, said storytelling artist Mahmood Farooqui.

“You had a lot of Hindu nationalists and Hindu fundamentalists saying Urdu created Pakistan, so let’s ban it, said Farooqui. “There was a lot of discrimination against it in schools, the government did nothing to propagate it, or to help its cause. And that continues to be the state of affairs today.”

And while some people, like Nusrat Ansari, are motivated to learn Urdu, she admits the language is struggling.

“I have met a lot of people who are really interested in this language and who would like to learn it,” she said. “But I wouldn’t say that it’s very popular and everybody understands it. Most people haven’t been that exposed to it.”

This exposure will be harder to come by if the new Hindu nationalist government keeps favoring Hindi over India’s other languages. That would only compound the problems Urdu's already facing. But there are about 50 million native Urdu speakers in India — and others, like Ansari, who are rediscovering the language through its cultural heritage. So while Urdu may not have the same dominance in India it once did, it looks like there might still be a place for it in the country.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!