A Russian writer who wrote about the absurdity of life now has a street in Queens named after him

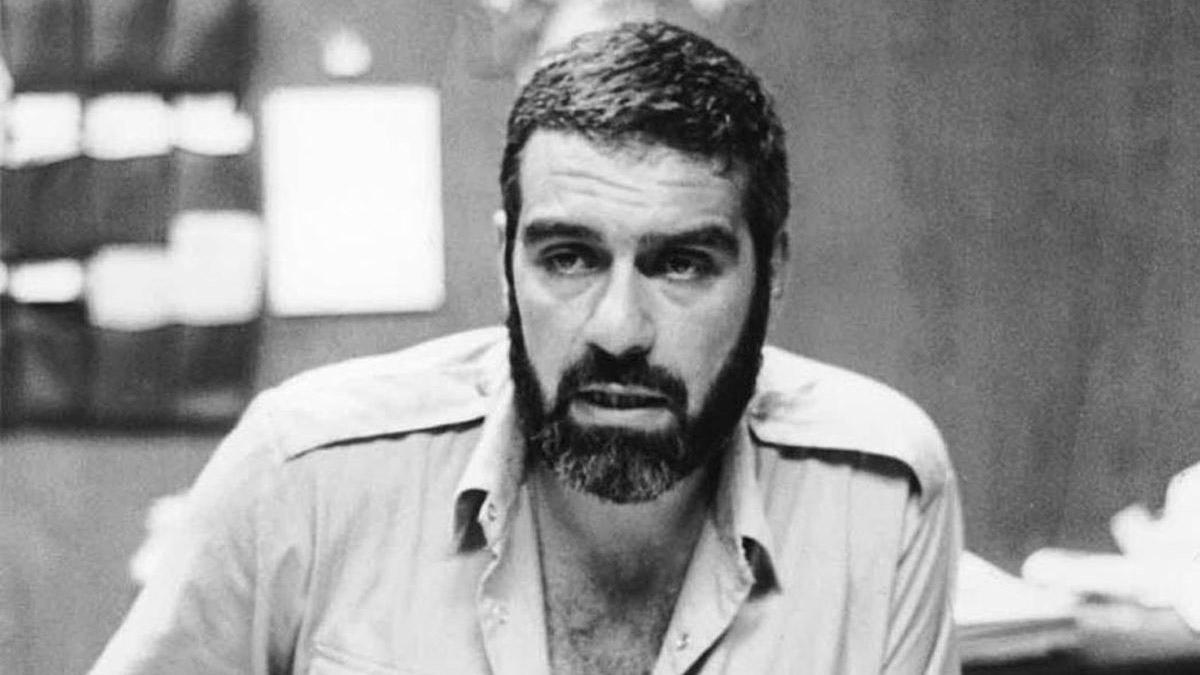

Sergei Dovlatov in 1980.

In this Queens neighborhood — wedged between competing airports — businesses can be three things at once, like a pizza, sushi and bagel shop. It's almost the definition of American diversity. And now, 63rd Drive here will soon be known as Sergei Dovlatov Way.

All it really took was 18,000 people signing a change.org petition, and a final signature from New York City's mayor, Bill de Blasio.

If you're Russian American, like me, you're likely quietly rejoicing about this. If not, it's more like, “Who is Sergei Dovlatov?”

Dovlatov is kind of the Bukowski of Russian literature. He battled his demons in the pages of his autobiographical novels, exploring both the absurdity of everyday life and the pain of alienation.

He had one of those epic 20th century lives: Working as a guard in Soviet prison camps, struggling in obscurity when his work was banned, and finally moving to New York under pressure from the KGB. But once in the US, Dovlatov's career thrived. His books were published here for the first time, and he lived just long enough to witness his popularity explode — in Russia, that is.

"I would get on the Metro and people would be reading the books, or I'd walk on a street and people would be sitting on a bench reading my Dad," says Dovlatov's daughter, Katherine.

Her translation of her father's novel "Pushkin Hills" was published in 2013. Sergei Dovlatov died of a heart attack in 1990, when he was only 49, but his wife Elena still lives in their apartment on 63rd Drive. Sitting on the couch in that apartment, I ask Elena what their life here was like.

“Our life looked like the life of all new immigrants,” she answers in Russian. “We survived everything that comes with that situation: Lack of money, difficulties with the culture and the stuff of everyday life."

"I remember life as being very loud in this apartment," says Dovlatov's daughter, Katherine. "He was big, he took a lot of space, there were always phone calls, he was always talking to somebody … It was full of life, that's how I remembered it — very loud and full of life.”

Katherine adds that people would come over — he was quite popular among the émigré and cultured circles — so people came to their apartment all the time.

Katherine adds that people would come over — he was quite popular among the émigré and cultured circles — so people came to their apartment all the time.

“They would always gather in this kitchen, and eat and drink and talk and discuss literature; as far as I can remember it was always about literature," she says. "After he died, it went quiet, so I remember that was a big transition and sort of a difficult thing to get used to."

I wondered what Dovlatov — whose writing was hardly sentimental — would have thought had he known one day his own street would bear his name.

“I think he probably would have joked something like, 'I told you kids you have a great Dad,'” says Katherine with a laugh. “Part of the émigréexperience is that, you know, kids don't really understand their parents. We start to speak different languages, we have different values, we just kind of grow apart a little bit because culturally we're different as well. So I think for my Dad, it was important back then that I understood that what he was doing was important, that literature was important, that he was somebody. Not just an immigrant loser who didn't have money.”

As for his wife, Elena, had she known this would happen someday?

“I would probably have rushed to America earlier,” she answers, laughing. “Earlier than we did.”

As it is, she's still getting used to the idea.

“Of course, it's an indescribable feeling, to suddenly leave home and find yourself on a street named after a member of your own family, and try to pretend that's a perfectly normal occurrence.”

Before I left, I asked them whether there was a single Dovlatov quote that might apply to the triumph and irony of the situation. They answer with a comment he once made about the paradoxical nature of his fame. In tandem, they say:

“I'm both surprised when I'm recognized and surprised when I'm not recognized.”

In this Queens neighborhood — wedged between competing airports — businesses can be three things at once, like a pizza, sushi and bagel shop. It's almost the definition of American diversity. And now, 63rd Drive here will soon be known as Sergei Dovlatov Way.

All it really took was 18,000 people signing a change.org petition, and a final signature from New York City's mayor, Bill de Blasio.

If you're Russian American, like me, you're likely quietly rejoicing about this. If not, it's more like, “Who is Sergei Dovlatov?”

Dovlatov is kind of the Bukowski of Russian literature. He battled his demons in the pages of his autobiographical novels, exploring both the absurdity of everyday life and the pain of alienation.

He had one of those epic 20th century lives: Working as a guard in Soviet prison camps, struggling in obscurity when his work was banned, and finally moving to New York under pressure from the KGB. But once in the US, Dovlatov's career thrived. His books were published here for the first time, and he lived just long enough to witness his popularity explode — in Russia, that is.

"I would get on the Metro and people would be reading the books, or I'd walk on a street and people would be sitting on a bench reading my Dad," says Dovlatov's daughter, Katherine.

Her translation of her father's novel "Pushkin Hills" was published in 2013. Sergei Dovlatov died of a heart attack in 1990, when he was only 49, but his wife Elena still lives in their apartment on 63rd Drive. Sitting on the couch in that apartment, I ask Elena what their life here was like.

“Our life looked like the life of all new immigrants,” she answers in Russian. “We survived everything that comes with that situation: Lack of money, difficulties with the culture and the stuff of everyday life."

"I remember life as being very loud in this apartment," says Dovlatov's daughter, Katherine. "He was big, he took a lot of space, there were always phone calls, he was always talking to somebody … It was full of life, that's how I remembered it — very loud and full of life.”

Katherine adds that people would come over — he was quite popular among the émigré and cultured circles — so people came to their apartment all the time.

Katherine adds that people would come over — he was quite popular among the émigré and cultured circles — so people came to their apartment all the time.

“They would always gather in this kitchen, and eat and drink and talk and discuss literature; as far as I can remember it was always about literature," she says. "After he died, it went quiet, so I remember that was a big transition and sort of a difficult thing to get used to."

I wondered what Dovlatov — whose writing was hardly sentimental — would have thought had he known one day his own street would bear his name.

“I think he probably would have joked something like, 'I told you kids you have a great Dad,'” says Katherine with a laugh. “Part of the émigréexperience is that, you know, kids don't really understand their parents. We start to speak different languages, we have different values, we just kind of grow apart a little bit because culturally we're different as well. So I think for my Dad, it was important back then that I understood that what he was doing was important, that literature was important, that he was somebody. Not just an immigrant loser who didn't have money.”

As for his wife, Elena, had she known this would happen someday?

“I would probably have rushed to America earlier,” she answers, laughing. “Earlier than we did.”

As it is, she's still getting used to the idea.

“Of course, it's an indescribable feeling, to suddenly leave home and find yourself on a street named after a member of your own family, and try to pretend that's a perfectly normal occurrence.”

Before I left, I asked them whether there was a single Dovlatov quote that might apply to the triumph and irony of the situation. They answer with a comment he once made about the paradoxical nature of his fame. In tandem, they say:

“I'm both surprised when I'm recognized and surprised when I'm not recognized.”

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!