How music helped one Ghanaian fight off loneliness during his first days in America

In 1979, Abu Eghan came to the United States from Ghana, to study at Ohio State University in Columbus.

His plan? Get his degree and return home to teach. But as Ghana’s political situation grew worse, following a military coup, Eghan’s family and friends warned him about coming back. Professional prospects looked dim. It was a reality that left Eghan lonely in Ohio.

He recalls the process of arranging phone calls home. “Telecommunication in Ghana was very, very backward,” Eghan says. “If you wanted to make a call, you had to write them a letter and let them know when you [were] going to call.” That’s because most of Eghan’s family lived in rural areas and needed to journey to the nearest city, Kumasi, to take calls.

Another option: mailing recordings of himself talking about life in America back home. “I would actually sit down and compose what I wanted to tell them, paragraph by paragraph, or maybe point by point, and then make a 30-minute tape and mail the tape to them,” he recalls.

And sometimes, his family would do the same, including his mother. She could not read or write or always make the trip to Kumasi to accept Eghan’s call. So the tapes were how they could hear each other's voice.

“Most of the time, when my mom sent me a tape, she was complaining," Eghan says. "By this time in Ghana, you know the early 80s, the coup that happened in ‘79 had really taken over. I mean there were sanctions against the country. They were really, really struggling.”

He remembers the things his mother used to say, “Why don't I finish and start something [in Ghana]? People are suffering.” She did not understand why his graduate studies took so long.

Along with the tapes from his mother, he found himself listening to Ghanaian music — thanks to a fortunate exchange he had with one of his nephews on his last day in Ghana.

He remembers his nephew asking him if he'd take along any Ghanaian music.

“What would I need that for? Most of the good music is out there,” Eghan said, referring to the US. His nephew refused to believe that and made Eghan a set of 10 mixed-tapes overnight. “You are going to need them,” Eghans remembers his cousin saying.

And he did, especially during those lonely moments in Ohio when he felt powerless and isolated, Eghan says.

“There is one specific song that I used to play and cry,” he says.

The song is “Baabi Dehyee” by J.A. Adolfo and The City Boys. Sung in the Twi language. “It’s about a prince in a strange kingdom,” Eghan says. “When a prince travels to someone's land, they can easily become a servant.” The song uses the metaphor of a river and says that “a tributary of a big river is regarded as a slave to that river.”

Eghan says the song consoled him when he felt like “just another international student in Ohio.”

“I knew there was going to be a payback, but in the meantime I was struggling,” he says. The song still reminds Eghan of those early days in the US and “brings tears to my eyes.”

First Days is a project inspired by Philadelphia’s South Asian American Digital Archive.

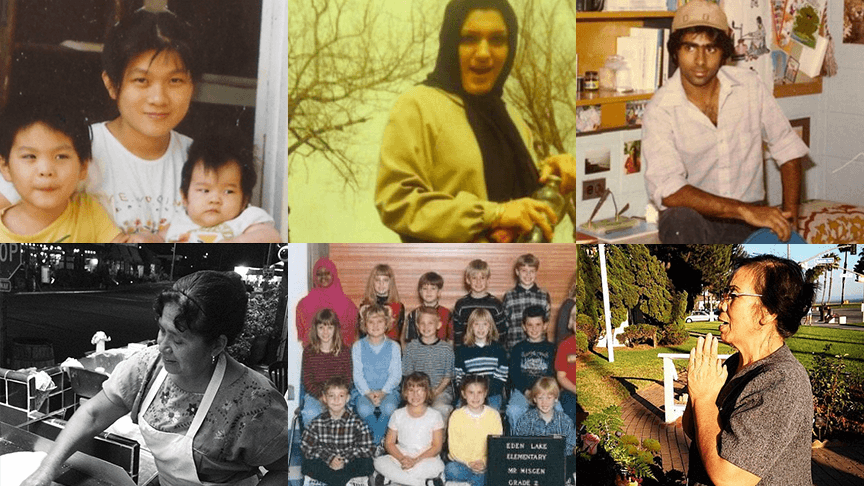

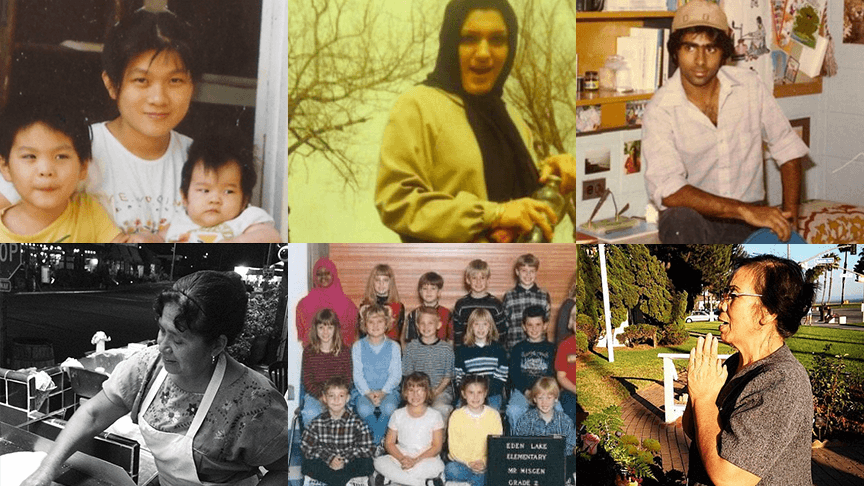

Check out more stories from First Days:

In 1979, Abu Eghan came to the United States from Ghana, to study at Ohio State University in Columbus.

His plan? Get his degree and return home to teach. But as Ghana’s political situation grew worse, following a military coup, Eghan’s family and friends warned him about coming back. Professional prospects looked dim. It was a reality that left Eghan lonely in Ohio.

He recalls the process of arranging phone calls home. “Telecommunication in Ghana was very, very backward,” Eghan says. “If you wanted to make a call, you had to write them a letter and let them know when you [were] going to call.” That’s because most of Eghan’s family lived in rural areas and needed to journey to the nearest city, Kumasi, to take calls.

Another option: mailing recordings of himself talking about life in America back home. “I would actually sit down and compose what I wanted to tell them, paragraph by paragraph, or maybe point by point, and then make a 30-minute tape and mail the tape to them,” he recalls.

And sometimes, his family would do the same, including his mother. She could not read or write or always make the trip to Kumasi to accept Eghan’s call. So the tapes were how they could hear each other's voice.

“Most of the time, when my mom sent me a tape, she was complaining," Eghan says. "By this time in Ghana, you know the early 80s, the coup that happened in ‘79 had really taken over. I mean there were sanctions against the country. They were really, really struggling.”

He remembers the things his mother used to say, “Why don't I finish and start something [in Ghana]? People are suffering.” She did not understand why his graduate studies took so long.

Along with the tapes from his mother, he found himself listening to Ghanaian music — thanks to a fortunate exchange he had with one of his nephews on his last day in Ghana.

He remembers his nephew asking him if he'd take along any Ghanaian music.

“What would I need that for? Most of the good music is out there,” Eghan said, referring to the US. His nephew refused to believe that and made Eghan a set of 10 mixed-tapes overnight. “You are going to need them,” Eghans remembers his cousin saying.

And he did, especially during those lonely moments in Ohio when he felt powerless and isolated, Eghan says.

“There is one specific song that I used to play and cry,” he says.

The song is “Baabi Dehyee” by J.A. Adolfo and The City Boys. Sung in the Twi language. “It’s about a prince in a strange kingdom,” Eghan says. “When a prince travels to someone's land, they can easily become a servant.” The song uses the metaphor of a river and says that “a tributary of a big river is regarded as a slave to that river.”

Eghan says the song consoled him when he felt like “just another international student in Ohio.”

“I knew there was going to be a payback, but in the meantime I was struggling,” he says. The song still reminds Eghan of those early days in the US and “brings tears to my eyes.”

First Days is a project inspired by Philadelphia’s South Asian American Digital Archive.

Check out more stories from First Days: