A history of Hebrew, told one word at a time

Ben and Jerry’s ice cream in Israel is labeled “glida,” the Aramaic word for frost. In modern Hebrew, it means ice cream.

The "Oxford English Dictionary" traces the history of words over centuries.

In Israel, linguists are still compiling a similar dictionary for the ancient Hebrew language.

English as we know it has been around about 860 years.

“Without bragging, the history of Hebrew is much older,” said Gabriel Birnbaum, a senior researcher at Israel’s official Academy of the Hebrew Language. About three times older.

Birnbaum’s job is to write the entries for the "Hebrew Historical Dictionary." Four days a week, seven hours a day, he sits alone in his small office, surrounded by dusty volumes of ancient Hebrew texts, and types out definitions.

“The ideal is to have all the words with all their history, how they started, when they started to be used, the whole of the treasure of the Hebrew language,” said Birnbaum. “The English have it, the French have it, the Hungarians have it, so we should also have it.”

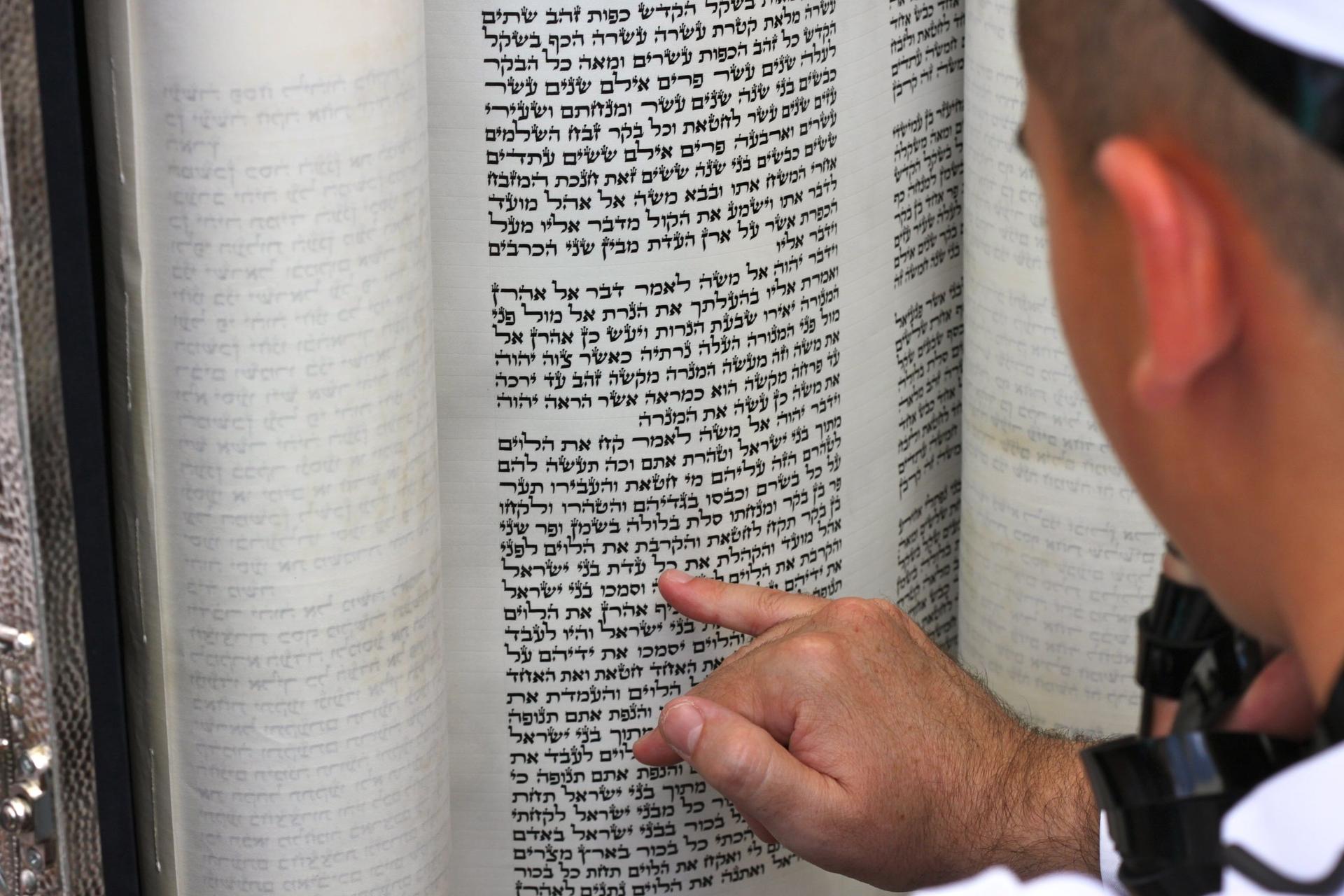

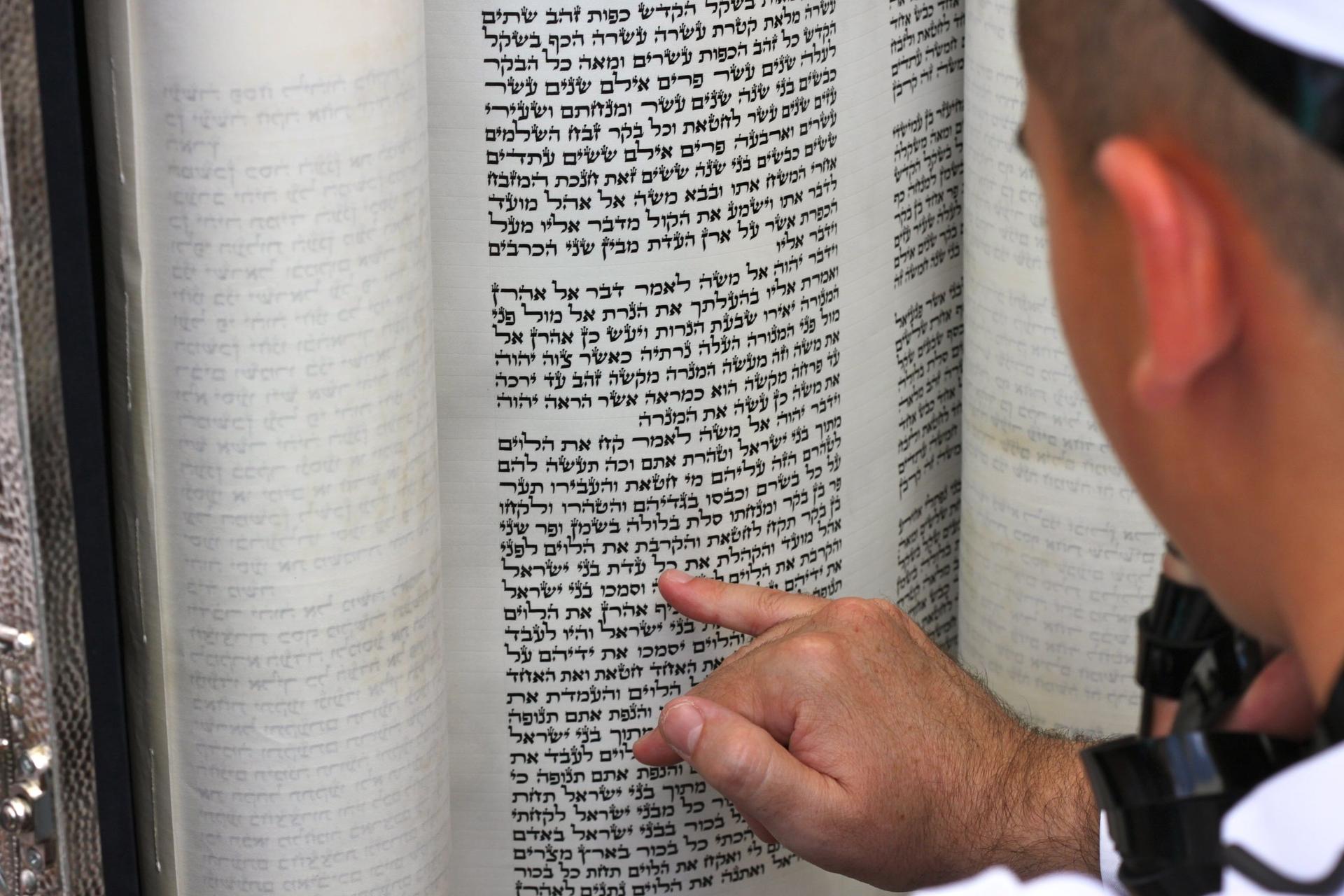

Hebrew was born around the 12th century BC. It’s the language of the Bible; Jesus knew Hebrew. But a few decades after Jesus’ death, Jews were exiled from the Holy Land, and they adopted different languages.

“Hebrew for 1,700 years wasn’t spoken by anyone,” Birnbaum said. “Some people call it a dead language. But if it was dead, it was a very lively corpse.”

It really wasn’t dead at all. Jews wrote their literature and liturgy in Hebrew, and recited prayers in Hebrew, as they do to this day. In the late 19th century, waves of Jews moved to the Holy Land, and revived Hebrew as a spoken language.

It really wasn’t dead at all. Jews wrote their literature and liturgy in Hebrew, and recited prayers in Hebrew, as they do to this day. In the late 19th century, waves of Jews moved to the Holy Land, and revived Hebrew as a spoken language.

But how do you order ice cream in an ancient tongue?

“They didn’t have words for office, or eyeglasses, or for matches,” said Birnbaum. “So from where will we take this? Of course we can coin new words. But first we have to use all the words we have in our sources.”

That’s how the mysterious Biblical word chashmal, referring to God appearing with fire and light, became the modern word for electricity. In an ancient Aramaic translation of a Biblical passage, manna from heaven is described as thin as frost, or glida. Today, glida is the frosty stuff you order at the ice cream parlor.

Hebrew is based on “roots,” patterns of letters that are the building blocks of the language. The three-letter combination in the word “write” also appears in the words for “article,” “reporter,” “letter,” “spelling,” “address,” and anything having to do with writing.

More than half of the roots in modern Hebrew come straight from the Bible.

“If I give you a text of Old English, you won’t understand a word. Those words have changed a lot,” Birnbaum said. “Now you take an Israeli child, you give him a text from the Book of Genesis, or a text from the Book of Samuel, he can understand, not to exaggerate, 70 percent of it. He can understand it.”

The Hebrew Language Academy began compiling its historical dictionary in 1959, but only came out with a first edition in 2005. There are many words from the past few thousand years to comb through, not to mention all the new words of the last century.

Linguists at the Hebrew Language Academy are still coining new words for terms that didn’t exist in the Bible or the Middle Ages – and Israelis often email the language academy to request new words.

Staffer Tzipi Senderov said there’s been high demand lately for one particular word.

“People always write the same thing. ‘I need to know the Hebrew term for cupcake,’” Senderov said. “Then we have to say, ‘There is no alternative,’ and people are like, ‘Why, can’t you find an alternative?’”

They did. The Hebrew Language Academy has posted two options online for the public to choose from. So far the more popular choice is ugoneet, which in English translates to "mini-cake." The other contender is mufeen mekushat, or “decorated muffin.”

Do these alternatives to cupcake sound tasty?

“No, and it wouldn’t catch, whatsoever,” Senderov said. “That’s the problem.”

All the Hebrew Language Academy’s new words will eventually end up in the historical dictionary. But sometimes, its new words just don’t catch on.

At birthday parties across Israel, a cupcake may just stay a cupcake.

The World in Words podcast is on Facebook and iTunes.

The "Oxford English Dictionary" traces the history of words over centuries.

In Israel, linguists are still compiling a similar dictionary for the ancient Hebrew language.

English as we know it has been around about 860 years.

“Without bragging, the history of Hebrew is much older,” said Gabriel Birnbaum, a senior researcher at Israel’s official Academy of the Hebrew Language. About three times older.

Birnbaum’s job is to write the entries for the "Hebrew Historical Dictionary." Four days a week, seven hours a day, he sits alone in his small office, surrounded by dusty volumes of ancient Hebrew texts, and types out definitions.

“The ideal is to have all the words with all their history, how they started, when they started to be used, the whole of the treasure of the Hebrew language,” said Birnbaum. “The English have it, the French have it, the Hungarians have it, so we should also have it.”

Hebrew was born around the 12th century BC. It’s the language of the Bible; Jesus knew Hebrew. But a few decades after Jesus’ death, Jews were exiled from the Holy Land, and they adopted different languages.

“Hebrew for 1,700 years wasn’t spoken by anyone,” Birnbaum said. “Some people call it a dead language. But if it was dead, it was a very lively corpse.”

It really wasn’t dead at all. Jews wrote their literature and liturgy in Hebrew, and recited prayers in Hebrew, as they do to this day. In the late 19th century, waves of Jews moved to the Holy Land, and revived Hebrew as a spoken language.

It really wasn’t dead at all. Jews wrote their literature and liturgy in Hebrew, and recited prayers in Hebrew, as they do to this day. In the late 19th century, waves of Jews moved to the Holy Land, and revived Hebrew as a spoken language.

But how do you order ice cream in an ancient tongue?

“They didn’t have words for office, or eyeglasses, or for matches,” said Birnbaum. “So from where will we take this? Of course we can coin new words. But first we have to use all the words we have in our sources.”

That’s how the mysterious Biblical word chashmal, referring to God appearing with fire and light, became the modern word for electricity. In an ancient Aramaic translation of a Biblical passage, manna from heaven is described as thin as frost, or glida. Today, glida is the frosty stuff you order at the ice cream parlor.

Hebrew is based on “roots,” patterns of letters that are the building blocks of the language. The three-letter combination in the word “write” also appears in the words for “article,” “reporter,” “letter,” “spelling,” “address,” and anything having to do with writing.

More than half of the roots in modern Hebrew come straight from the Bible.

“If I give you a text of Old English, you won’t understand a word. Those words have changed a lot,” Birnbaum said. “Now you take an Israeli child, you give him a text from the Book of Genesis, or a text from the Book of Samuel, he can understand, not to exaggerate, 70 percent of it. He can understand it.”

The Hebrew Language Academy began compiling its historical dictionary in 1959, but only came out with a first edition in 2005. There are many words from the past few thousand years to comb through, not to mention all the new words of the last century.

Linguists at the Hebrew Language Academy are still coining new words for terms that didn’t exist in the Bible or the Middle Ages – and Israelis often email the language academy to request new words.

Staffer Tzipi Senderov said there’s been high demand lately for one particular word.

“People always write the same thing. ‘I need to know the Hebrew term for cupcake,’” Senderov said. “Then we have to say, ‘There is no alternative,’ and people are like, ‘Why, can’t you find an alternative?’”

They did. The Hebrew Language Academy has posted two options online for the public to choose from. So far the more popular choice is ugoneet, which in English translates to "mini-cake." The other contender is mufeen mekushat, or “decorated muffin.”

Do these alternatives to cupcake sound tasty?

“No, and it wouldn’t catch, whatsoever,” Senderov said. “That’s the problem.”

All the Hebrew Language Academy’s new words will eventually end up in the historical dictionary. But sometimes, its new words just don’t catch on.

At birthday parties across Israel, a cupcake may just stay a cupcake.