25 years later, China still blames the US for somehow fomenting the Tiananmen Square protests

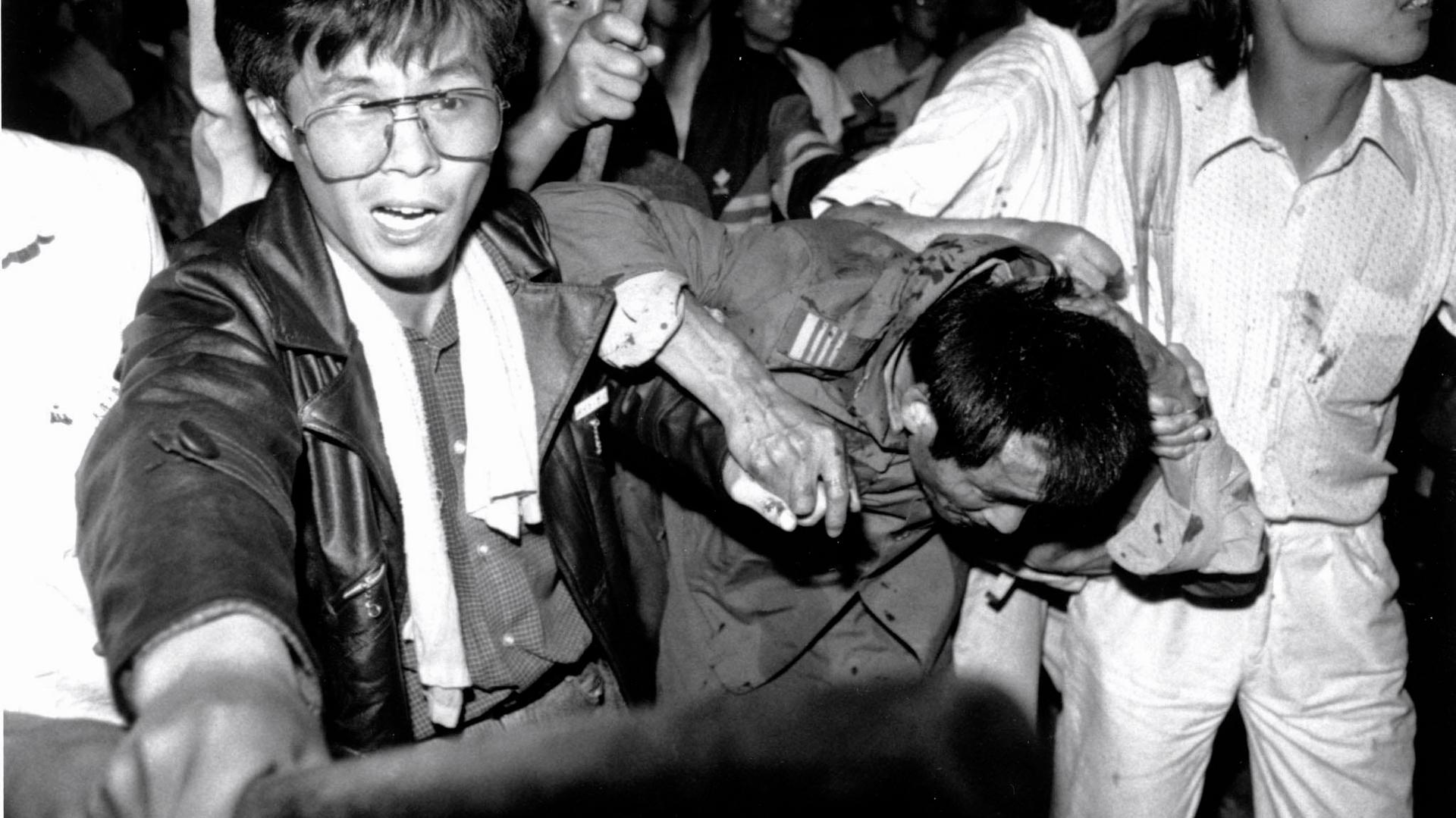

A captured tank driver is helped to safety by students as the crowd beats him on June 4, 1989.

Twenty-five years ago on Thursday, a political showdown was playing out on the streets of Beijing. Hundreds of thousands of people took part in student-led protests. And we all know how the story ended on June 4, 1989.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of what has come to be known as the “Tiananmen Square massacre,” when Chinese troops opened fire on unarmed civilians, bringing a sudden and bloody halt to that protest movement.

John Pomfret was in Beijing in 1989 covering those events for the Associated Press. He says 25 years ago today, "around a million people were on the streets protesting, calling on the Chinese government to give them greater freedom, including press freedom and the freedom to associate, as well. Nobody really knew what was going to happen next."

But Pomfret says people had a sense, from the in-fighting within the Communist Party, "that there was going to be some type of a difficult end to the problem. There was no real sense that the Communist Party, or any factions within it, were seriously interested in embracing some type of significant political reform."

PRI's The World host Marco Werman interviewed Pomfret about what happened next and what it has meant for US-China relations.

In the days after the crackdown after June 4th, you were kicked out of China. What happened?

I was called up by Chinese police and interrogated for several hours and then I was given three days to leave the country. They could have put me on the first plane out. My crimes were "stealing state secrets" and "violating martial law provisions." Two resident correspondents, one from Voice of America [VOA] — Al Pessin, were booted out.

Basically, I think the motivation for expelling a reporter from VOA and from the AP was that [government leaders in Beijing] were trying to express their irritation with what they alleged to be US government involvement in the protests. It had less to do with us and more to do with the fact that they wanted to express their anger at America for what they believed was fomenting this "counter-revolutionary rebellion."

What is the official Chinese government version of what happened in 1989? And has that narrative changed or evolved over time?

I think it actually has changed. Initially after the crackdown, the Chinese government called it the "June 4th Counter-Revolutionary Rebellion." But now that name has morphed into the “June 4th Incident.”

Around 1996-97, the Chinese government began allowing back people who had participated in the rebellion, but had fled or left China. Not the top leadership of the student movement, but lower level people. And they also, for example, let me back in. So there was a sense that not all sins were forgiven from their perspective, but that they were adopting a different view of it — less counter-revolutionary rebellion and more "incident," which implies that the historical judgment is yet to be made on such a thing. But since then, there’s been no significant change.

Are there still activist groups calling attention to June 4th?

In China, not so much. It’s not a growth industry, let’s say, because if you do call for a re-thinking of the incident, you invariably get visited by security officials. So, it’s not something that happens on a wide level.

There is now a generation of people who are quite successful financially who marched — whether in Beijing or Chengdu or Shanghai or other cities — and who have very positive feelings and memories from that period of time, and would very much support a re-thinking or re-evaluation of the movement. That said, I don’t think it’s going to happen any time soon.

How did the violent crackdown in 1989 impact the US-China relationship?

Immediately after the crackdown, President George Bush — the first Bush president — dispatched senior American officials to China to reassure the Chinese that the United States wanted to continue its strong relationship with China.

But on the Chinese side, they really viewed the Tiananmen Square protest as being American-inspired, and so their paranoia about the United States increased significantly after that. And they launched the "patriotic education campaign movement," in which they instructed their students, their young, that America was basically out to change China, to push China toward a capitalist system or to a democracy.

Still to this day, within the Communist Party, they say that the United States and "Western imperialist forces" are continuing to plot to bring down the Communist Party of China. So, I think that experience of Tiananmen Square was a seminal experience that the Party had, that it used to convince itself that America wanted to take China down.

What do you think this 25th anniversary is going to mean for people in China?

First, there's a whole generation of people who never experienced it because they weren't born. That's the student generation. Secondly, there is a very strong crackdown right now in China on civil society. And so, the police forces in China are in no mood to tolerate anyone calling for a re-evaluation of the Tiananmen Square incident. Thirdly, there's been an uptick in China of violent attacks — probably by the Uighur ethnic goup — and that's probably increased a lot of skittishness and paranoia on the part of security forces. My sense is that if there is a renewed call for evaluation of the [Tiananmen] incident, it will be met with the full force of the Chinese security services.

Twenty-five years ago on Thursday, a political showdown was playing out on the streets of Beijing. Hundreds of thousands of people took part in student-led protests. And we all know how the story ended on June 4, 1989.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of what has come to be known as the “Tiananmen Square massacre,” when Chinese troops opened fire on unarmed civilians, bringing a sudden and bloody halt to that protest movement.

John Pomfret was in Beijing in 1989 covering those events for the Associated Press. He says 25 years ago today, "around a million people were on the streets protesting, calling on the Chinese government to give them greater freedom, including press freedom and the freedom to associate, as well. Nobody really knew what was going to happen next."

But Pomfret says people had a sense, from the in-fighting within the Communist Party, "that there was going to be some type of a difficult end to the problem. There was no real sense that the Communist Party, or any factions within it, were seriously interested in embracing some type of significant political reform."

PRI's The World host Marco Werman interviewed Pomfret about what happened next and what it has meant for US-China relations.

In the days after the crackdown after June 4th, you were kicked out of China. What happened?

I was called up by Chinese police and interrogated for several hours and then I was given three days to leave the country. They could have put me on the first plane out. My crimes were "stealing state secrets" and "violating martial law provisions." Two resident correspondents, one from Voice of America [VOA] — Al Pessin, were booted out.

Basically, I think the motivation for expelling a reporter from VOA and from the AP was that [government leaders in Beijing] were trying to express their irritation with what they alleged to be US government involvement in the protests. It had less to do with us and more to do with the fact that they wanted to express their anger at America for what they believed was fomenting this "counter-revolutionary rebellion."

What is the official Chinese government version of what happened in 1989? And has that narrative changed or evolved over time?

I think it actually has changed. Initially after the crackdown, the Chinese government called it the "June 4th Counter-Revolutionary Rebellion." But now that name has morphed into the “June 4th Incident.”

Around 1996-97, the Chinese government began allowing back people who had participated in the rebellion, but had fled or left China. Not the top leadership of the student movement, but lower level people. And they also, for example, let me back in. So there was a sense that not all sins were forgiven from their perspective, but that they were adopting a different view of it — less counter-revolutionary rebellion and more "incident," which implies that the historical judgment is yet to be made on such a thing. But since then, there’s been no significant change.

Are there still activist groups calling attention to June 4th?

In China, not so much. It’s not a growth industry, let’s say, because if you do call for a re-thinking of the incident, you invariably get visited by security officials. So, it’s not something that happens on a wide level.

There is now a generation of people who are quite successful financially who marched — whether in Beijing or Chengdu or Shanghai or other cities — and who have very positive feelings and memories from that period of time, and would very much support a re-thinking or re-evaluation of the movement. That said, I don’t think it’s going to happen any time soon.

How did the violent crackdown in 1989 impact the US-China relationship?

Immediately after the crackdown, President George Bush — the first Bush president — dispatched senior American officials to China to reassure the Chinese that the United States wanted to continue its strong relationship with China.

But on the Chinese side, they really viewed the Tiananmen Square protest as being American-inspired, and so their paranoia about the United States increased significantly after that. And they launched the "patriotic education campaign movement," in which they instructed their students, their young, that America was basically out to change China, to push China toward a capitalist system or to a democracy.

Still to this day, within the Communist Party, they say that the United States and "Western imperialist forces" are continuing to plot to bring down the Communist Party of China. So, I think that experience of Tiananmen Square was a seminal experience that the Party had, that it used to convince itself that America wanted to take China down.

What do you think this 25th anniversary is going to mean for people in China?

First, there's a whole generation of people who never experienced it because they weren't born. That's the student generation. Secondly, there is a very strong crackdown right now in China on civil society. And so, the police forces in China are in no mood to tolerate anyone calling for a re-evaluation of the Tiananmen Square incident. Thirdly, there's been an uptick in China of violent attacks — probably by the Uighur ethnic goup — and that's probably increased a lot of skittishness and paranoia on the part of security forces. My sense is that if there is a renewed call for evaluation of the [Tiananmen] incident, it will be met with the full force of the Chinese security services.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?