Faced with dire climate change, denial may actually help Australian farmers cope

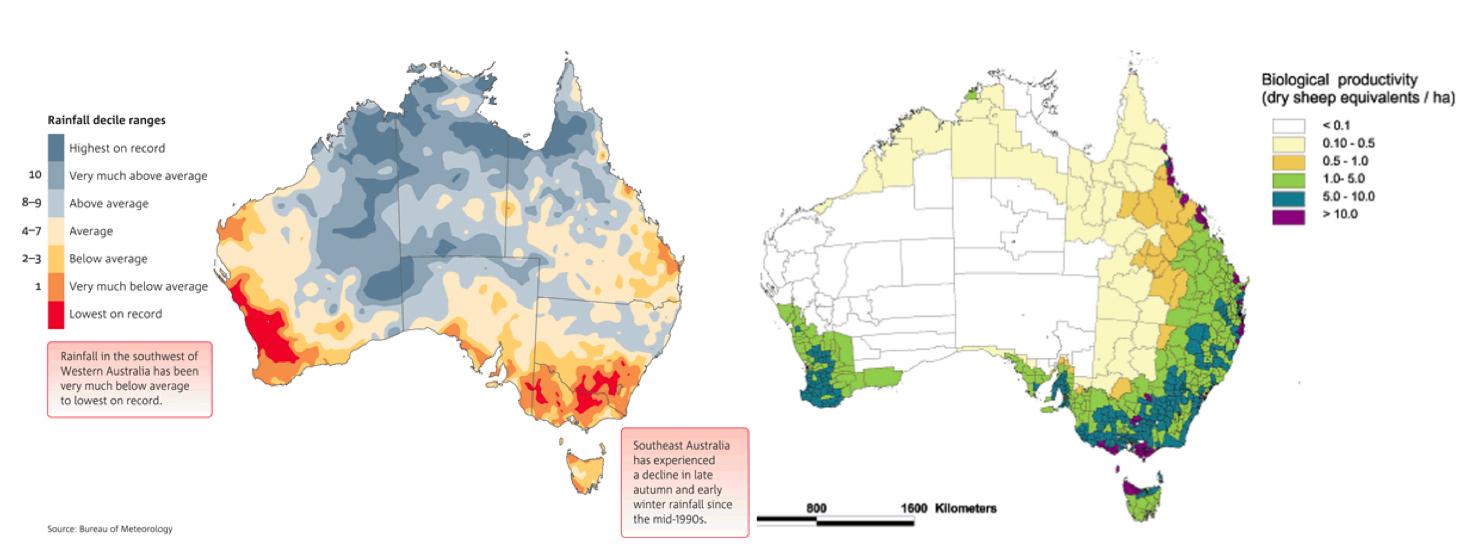

Southeastern and southwestern Australia have experienced some of the country’s most severe rainy season droughts over the last two decades (L). These are also some of the country’s most productive agricultural regions (R).

In Australia, government researchers say climate change has definitely hit the country, hard.

In its State of the Climate 2014 report, Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology cites a nearly two degree Fahrenheit rise in the country’s average temperature since 1910, with seven of the ten hottest years on record having occurred since 1998. Across much of Australia, there’s been more “extreme fire weather” — days with wind, high temperature, low humidity and drought.

The Millennium Drought is an example of the extreme weather Australia has been experiencing. Beginning in the late 1990s, this terrible period of dryness struck southern Australia. Crops failed. Farm ponds dried up. With no water and little grass, ranchers had to shoot their cattle. The catastrophe lasted a decade, and it was quickly followed by another drought.

While no one weather event can be blamed on climate change, the Millennium Drought may be just a taste of what is in store for Australia as the earth continues to warm. But try convincing farmers in New South Wales that they face more frequent droughts and heat waves.

“At this stage I’m a skeptic,” says apple farmer Peter Darley.

“I don’t go much on the politics of climate change,” echoes rancher Graham Brown. “Climate variability has been with us since the dawn of time.”

Related: Australians look for psychological resilience to a changing climate

Brown’s wife, Annette, recites a popular poem to support her claim that what Australia is facing is nothing new. “My Country,” written by Dorothea Mackellar in 1908, speaks of Australia’s “droughts and flooding rains,” “a pitiless blue sky,” and “flood and fire and famine.”

At a recent meeting of the local Country Women’s Association in Orange, New South Wales, about two-thirds of the women raised their hands when asked how many of them did not believe in climate change.

Many people, for many reasons, do not believe that manmade climate change is occurring. To climate activists, such skeptics are often labeled “deniers,” and their lack of belief is often framed as a political position.

But some mental health experts, including David Perkins of Australia’s University of Newcastle, say that denial — at least in the short run — can be a practical response to a tough situation.

“It’s very hard to admit that the world is falling apart,” he says.

Farmers in particular are used to being able to fix things, he adds. “To have a problem where they think they can’t find a solution is actually, I think, psychologically very threatening, and therefore denying in a psychological way may be a better way of dealing with it.”

In other words, as long as farmers prepare for the next big weather event — and the New South Wales farmers I met say they are careful to do that — does it really matter if they don’t foresee a whole lot more droughts and heat waves in the next 50 or 100 years?

“As farmers, we just adjust to it,” says Graham Brown. “We have to live with the weather we’re handed out.”

And worrying about the weather can have a negative impact on mental health. Studies show — and farmers admit — that droughts can generate a great amount of stress, which can lead to depression. Suicide rates appear to increase in rural areas during droughts. It’s something farmers talk about a lot.

During droughts, ranchers are busy day and night hauling water, searching for hay and “destocking” — killing off cattle because of a lack of water or feed. “If you have that really really bad day the next day, and the next day, and the next day, and the next … it really starts knocking you about,” says farmer Reg Kidd.

“All of us operate with a level of denial,” says Grant Blashki, a Melbourne physician who studies the health effects of climate change. “We could dig ourselves into a real pessimistic, nihilistic hole if we want to” by obsessing about all sorts of terrible things, from disease to poverty to nuclear war. “But it’s not going to help at all.”

But while denial can be helpful for individuals — and doesn’t call for treatment — Blashki says it is unhelpful for society if everyone rejects what scientists have learned about climate change. “I do think that people in positions of authority and positions of responsibility in government, in big businesses, do have a responsibility to really take a long view,” he says.

Yet in Australia, the public is going the opposite way. Denial is on the upswing. According to one survey, the percentage of Australians who say they are concerned about climate change has dropped from 73 percent to 57 percent from 2007 to 2012, even as the science is getting more and more certain.

Reporting for this story was supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

In Australia, government researchers say climate change has definitely hit the country, hard.

In its State of the Climate 2014 report, Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology cites a nearly two degree Fahrenheit rise in the country’s average temperature since 1910, with seven of the ten hottest years on record having occurred since 1998. Across much of Australia, there’s been more “extreme fire weather” — days with wind, high temperature, low humidity and drought.

The Millennium Drought is an example of the extreme weather Australia has been experiencing. Beginning in the late 1990s, this terrible period of dryness struck southern Australia. Crops failed. Farm ponds dried up. With no water and little grass, ranchers had to shoot their cattle. The catastrophe lasted a decade, and it was quickly followed by another drought.

While no one weather event can be blamed on climate change, the Millennium Drought may be just a taste of what is in store for Australia as the earth continues to warm. But try convincing farmers in New South Wales that they face more frequent droughts and heat waves.

“At this stage I’m a skeptic,” says apple farmer Peter Darley.

“I don’t go much on the politics of climate change,” echoes rancher Graham Brown. “Climate variability has been with us since the dawn of time.”

Related: Australians look for psychological resilience to a changing climate

Brown’s wife, Annette, recites a popular poem to support her claim that what Australia is facing is nothing new. “My Country,” written by Dorothea Mackellar in 1908, speaks of Australia’s “droughts and flooding rains,” “a pitiless blue sky,” and “flood and fire and famine.”

At a recent meeting of the local Country Women’s Association in Orange, New South Wales, about two-thirds of the women raised their hands when asked how many of them did not believe in climate change.

Many people, for many reasons, do not believe that manmade climate change is occurring. To climate activists, such skeptics are often labeled “deniers,” and their lack of belief is often framed as a political position.

But some mental health experts, including David Perkins of Australia’s University of Newcastle, say that denial — at least in the short run — can be a practical response to a tough situation.

“It’s very hard to admit that the world is falling apart,” he says.

Farmers in particular are used to being able to fix things, he adds. “To have a problem where they think they can’t find a solution is actually, I think, psychologically very threatening, and therefore denying in a psychological way may be a better way of dealing with it.”

In other words, as long as farmers prepare for the next big weather event — and the New South Wales farmers I met say they are careful to do that — does it really matter if they don’t foresee a whole lot more droughts and heat waves in the next 50 or 100 years?

“As farmers, we just adjust to it,” says Graham Brown. “We have to live with the weather we’re handed out.”

And worrying about the weather can have a negative impact on mental health. Studies show — and farmers admit — that droughts can generate a great amount of stress, which can lead to depression. Suicide rates appear to increase in rural areas during droughts. It’s something farmers talk about a lot.

During droughts, ranchers are busy day and night hauling water, searching for hay and “destocking” — killing off cattle because of a lack of water or feed. “If you have that really really bad day the next day, and the next day, and the next day, and the next … it really starts knocking you about,” says farmer Reg Kidd.

“All of us operate with a level of denial,” says Grant Blashki, a Melbourne physician who studies the health effects of climate change. “We could dig ourselves into a real pessimistic, nihilistic hole if we want to” by obsessing about all sorts of terrible things, from disease to poverty to nuclear war. “But it’s not going to help at all.”

But while denial can be helpful for individuals — and doesn’t call for treatment — Blashki says it is unhelpful for society if everyone rejects what scientists have learned about climate change. “I do think that people in positions of authority and positions of responsibility in government, in big businesses, do have a responsibility to really take a long view,” he says.

Yet in Australia, the public is going the opposite way. Denial is on the upswing. According to one survey, the percentage of Australians who say they are concerned about climate change has dropped from 73 percent to 57 percent from 2007 to 2012, even as the science is getting more and more certain.

Reporting for this story was supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.