A young Iraqi hopes to unite and heal his country — through books

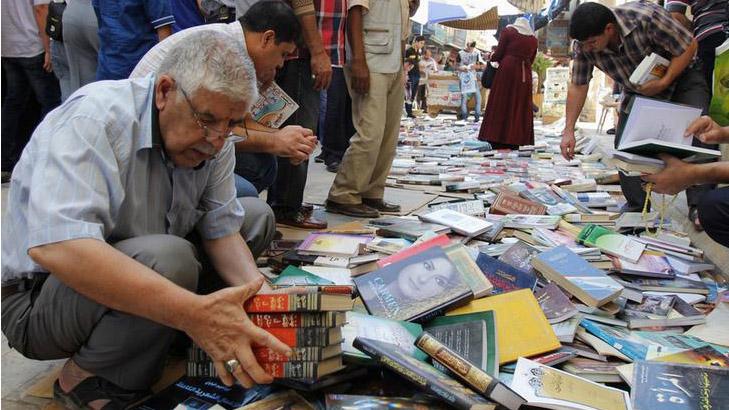

Residents shop for books at Mutanabi Street in Baghdad, September 27, 2013.

Ali al-Makhzomy is a young Iraqi on a mission. And that mission is to turn back the clock in Baghdad.

He wants to bring back the Baghdad of the 1930s, 40s and 50s. In those decades, he argues, the city was "more civilized." And his weapon to bring back that past is books.

Specifically, he is trying to encourage young Iraqis to read again.

A decade of war has left many of them disillusioned and pessimistic about the future of their country. Many have emigrated, and others are planning to leave Iraq.

The reason for the pessimism, says freelance journalist Jane Araf, is simple: "The country is pretty much broken … [when] the war came along, a lot of the institutions stopped working. The education system is in shambles and literacy has taken a hit."

Arraf, who has reported for many foreign news organizations, has been following the work of Ali al-Makhzomy to inspire young Iraqis to read again. Al-Makhzomy works for the Iraqi Ministry of Culture and has set up small, informal libraries in cafes around Baghdad. Young Iraqis hang out in these cafes and al-Makhzomy is hoping that, by putting books there, young people will become interested and pick up a book to read.

"The only libraries in Baghdad are in governmental institutions and you can't easily get to them and they're not open in the afternoon," says Arraf.

Al-Makhzomy has himself suffered from the violence in Iraq. His brother disappeared in 2005 and, like many Iraqis who've gone missing during the war, his brother is believed to have been killed, Arraf says.

"When you ask Ali, he says, 'we haven't lost hope,'" the journalist explains. "That might be true, but he's quite realistic about the circumstances he lives in."

Al-Makhzomy is quite determined to create change. He wants life to be better for all Iraqis.

His idea to set up small libraries might sound simple at first, says Arraf, but it could make a big difference.

Iraqis share a sense of pride in their long history and rich culture. By reminding them of their past and re-igniting their cultural pride, it might bring them together again and give youth hope for the future.

Ali al-Makhzomy is a young Iraqi on a mission. And that mission is to turn back the clock in Baghdad.

He wants to bring back the Baghdad of the 1930s, 40s and 50s. In those decades, he argues, the city was "more civilized." And his weapon to bring back that past is books.

Specifically, he is trying to encourage young Iraqis to read again.

A decade of war has left many of them disillusioned and pessimistic about the future of their country. Many have emigrated, and others are planning to leave Iraq.

The reason for the pessimism, says freelance journalist Jane Araf, is simple: "The country is pretty much broken … [when] the war came along, a lot of the institutions stopped working. The education system is in shambles and literacy has taken a hit."

Arraf, who has reported for many foreign news organizations, has been following the work of Ali al-Makhzomy to inspire young Iraqis to read again. Al-Makhzomy works for the Iraqi Ministry of Culture and has set up small, informal libraries in cafes around Baghdad. Young Iraqis hang out in these cafes and al-Makhzomy is hoping that, by putting books there, young people will become interested and pick up a book to read.

"The only libraries in Baghdad are in governmental institutions and you can't easily get to them and they're not open in the afternoon," says Arraf.

Al-Makhzomy has himself suffered from the violence in Iraq. His brother disappeared in 2005 and, like many Iraqis who've gone missing during the war, his brother is believed to have been killed, Arraf says.

"When you ask Ali, he says, 'we haven't lost hope,'" the journalist explains. "That might be true, but he's quite realistic about the circumstances he lives in."

Al-Makhzomy is quite determined to create change. He wants life to be better for all Iraqis.

His idea to set up small libraries might sound simple at first, says Arraf, but it could make a big difference.

Iraqis share a sense of pride in their long history and rich culture. By reminding them of their past and re-igniting their cultural pride, it might bring them together again and give youth hope for the future.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?