Scientists say they’ve found romantic love, in brain scans

A couple shares a romantic embrace.

Head to your local university library, and you’ll find shelves of books on courtship and marriage in history and in literature, and even more books about sex. But scholarly books about love? Not so much.

If you want to read about love, you’ll find a lot more in the self-help section of the bookstore. Books on why people fall in love with the people they fall in love with. Books on how to win love, how to keep love alive and how to get over heartache.

People have been fascinated with these questions for centuries, but only recently have academics turned to them in earnest. Historians, anthropologists, English literature professors and even neuroscientists have started taking love seriously.

Neurologist Lucy Brown says when she started studying love in the mid-1990s, work like hers was seen by many scholars as trivial — or too difficult.

“It seemed kind of an amorphous thing, romantic love,” Brown says.

In fact, the first time Senator William Proxmire gave out one of his famous Golden Fleece Awards, bestowed on researchers he saw as wasting government money, it went to a scholar studying passionate love.

But that was in the 1970s. Since then, love research has gained respect.

“The attitude is changing tremendously, and there are more people studying it now,” Brown says. “This is now in the mainstream psychological literature, that this is important to do.”

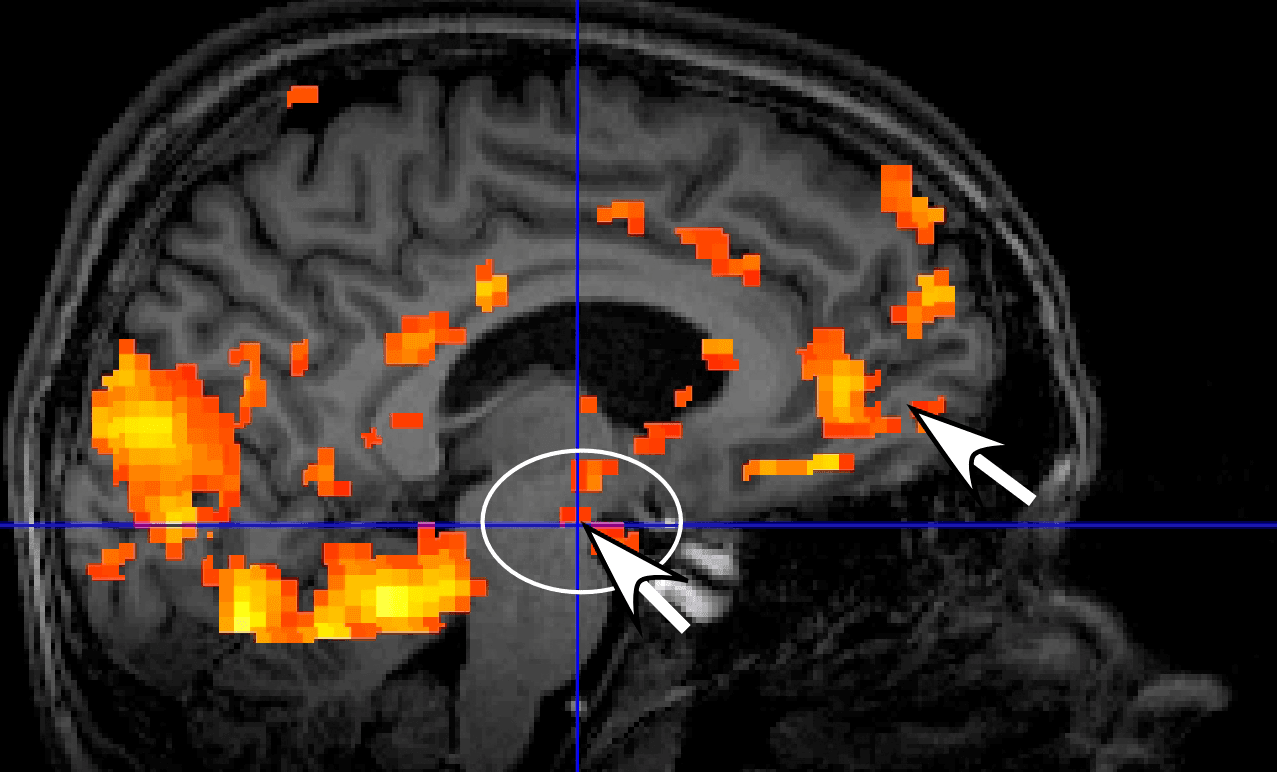

Brown is a professor of neurology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine. She uses an MRI machine to study the brains of the smitten. She’s found that when people who are madly in love think of their sweethearts, many parts of the brain are activated, but one thing all her study subjects had in common was activation in a “primitive” part of the brain just above the brainstem.

“People who have just gotten a shot of cocaine show activation in this exact same region,” she says. “This passion is part of one of our deepest, most important reward systems.”

She says this helps explain why love seems so addictive. And she says it supports her hypothesis: Romantic love is a drive, part of the human system for securing a mate. She believes the other two parts of that system are lust and attachment love, which show up in different parts of the brain and, Brown and her colleagues argue, make people behave differently.

Brown’s research partner, Rutgers University anthropologist Helen Fisher, argues that the romantic love drive is even stronger than the sex drive.

“If you ask somebody to go to bed with you and they say, ‘No thank you,’ you don’t kill yourself,” Fisher says. “But around the world people live for love, they pine for love, they kill for love, and they die for love — for a very important reason. It is with this person that you will form a pair bond and raise your children as a team and pass your DNA on into tomorrow.”

That doesn’t sound particularly romantic. And Brown and Fisher admit they’ve been accused of taking the magic and mystery out of love.

But Esquire writer AJ Jacobs doesn’t care if love is just a chemical reaction. “What a chemical reaction!” he says. “Why should it diminish it just because I know it’s just a bunch of neurons in my brain reacting in a certain way?”

Jacobs asked Brown and Fisher to scan his brain to see whether he really loved his wife. His scan showed a lot of activity in areas of the brain associated with attachment, but not so much with romance. And that’s fine with him.

“I am so thankful I’m over that phase of love,” Jacobs says. “Some people love the roller coaster emotions. I do not. I like sort of the Segway, or the people walker at the airport.”

Jacobs says we've "romanticized romance."

In an essay for Esquire, he compares the love lives of Charles Darwin and William Shakespeare. Darwin, he says, was pragmatic about marriage.

“Before he proposed to his wife, he wrote a pro/con list,” Jacobs says. And Darwin ended up having a very long and happy marriage.

Shakespeare, the man behind those “wonderful, passionate sonnets," was a different story.

"That guy had a terrible marriage,” according to Jacobs. Some people think Shakespeare cheated on his wife. And Jacobs points out that in Shakespeare's alleged will, he left his wife their "second-best bed" — and nothing more.

Jacobs says we might do better with a more rational approach to love, if we want to find happiness. So he’s offering some "Valentines for rational lovers” in the slideshow below.

You can download them to send to your Valentine. Better yet, suggest your own rational Valentine’s Day messages in the comments below. We'll turn the best into additional cards that you, and others, can send to that special, rational someone.

You’ll find much more on the science and culture of love and, on February 14, an hour-long radio special on love at The Really Big Questions website.

The World is an independent newsroom. We’re not funded by billionaires; instead, we rely on readers and listeners like you. As a listener, you’re a crucial part of our team and our global community. Your support is vital to running our nonprofit newsroom, and we can’t do this work without you. Will you support The World with a gift today? Donations made between now and Dec. 31 will be matched 1:1. Thanks for investing in our work!