Picturing the lives of refugees in the US, starting with their first night here

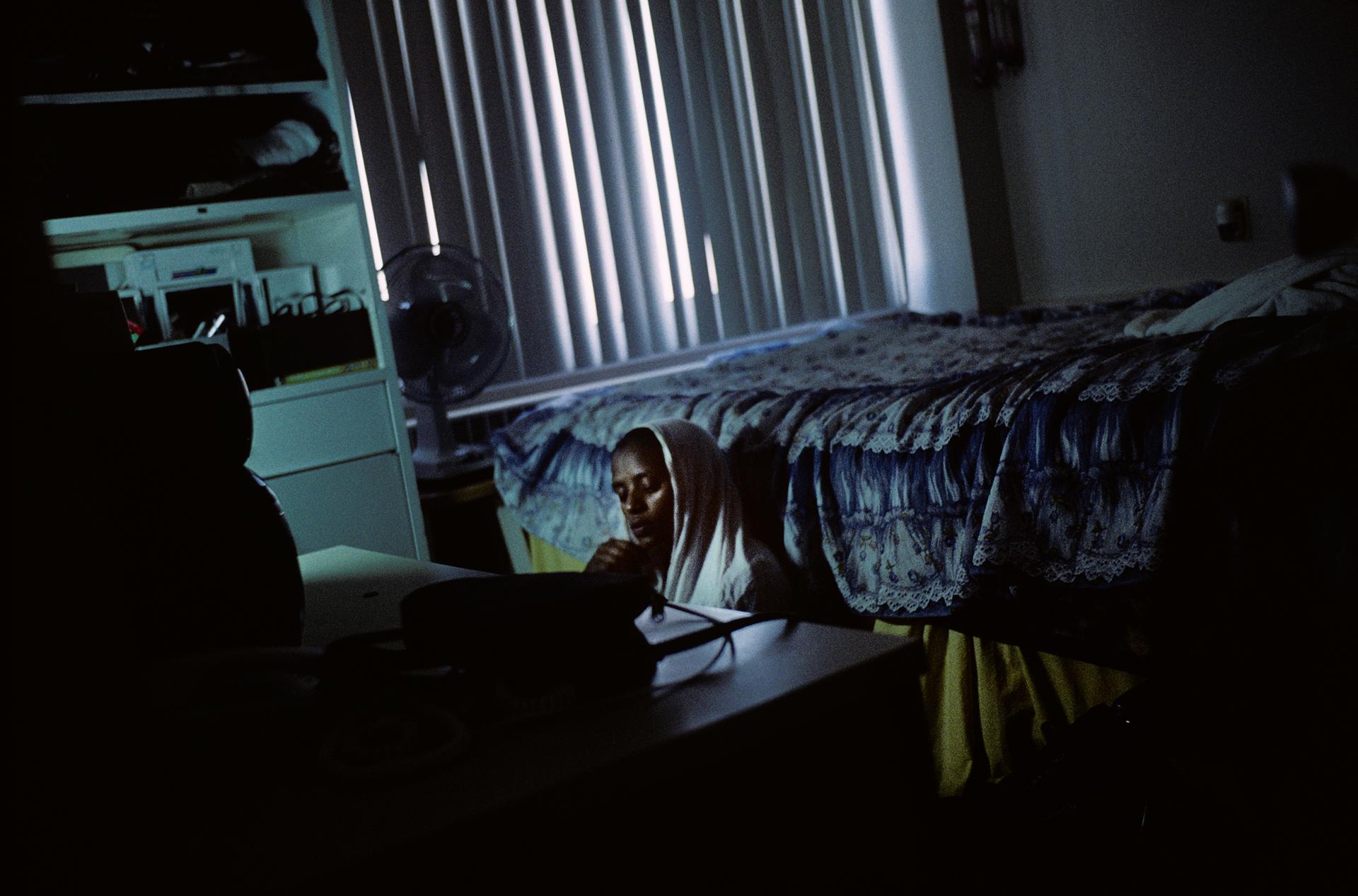

Fatima Barisu, a refugee from Somalia, on the day she arrived in Minneapolis in 2007 to be resettled.

Last year, nearly 60,000 refugees resettled in the United States. A recent book called "Refugee Hotel," and an exhibit up now in New York City based on the book, take a close look at the experiences of some of these people, meeting them on their first night in the United States.

The book is the result of six years of work by photographer Gabriele Stabile and journalist Juliet Linderman.

Stabile's images are filled with quiet, poignant moments: Two Burmese kids scrutinizing a Coca-Cola vending machine, a young Cuban refugee asleep in a chair, a man from Burundi gazing out an open door.

The project began when Stabile read aNew York Times article in 2006 about a nearby hotel where refugees regularly spent their first night in America, before catching flights to their final destinations. Soon he was spending all the time he could there, and at other hotels like it.

“On a human level, it was very concentrated because it all happens in a few hours, and it happens basically within the rooms,” Stabile says. “You could really feel the compassion and the fear, the nostalgia, the uncertainties.”

Along with taking pictures, he listened to the stories that people told, including that of a Somali family he photographed on their first night in the US.

“It’s something that broke my heart,” he says, remembering how the family was afraid of being left behind, so they decided to spend the night in the hallway. "They had a room," Stabile says, "they just didn’t trust that people would remember them once the door was closed.”

Ehney Hser did go into his hotel room. He is a refugee from an ethnic minority in Myanmar. Stabile first photographed him during a layover in Los Angeles. He didn’t quite know what to make of the room, though.

He and another refugee sharing his room were scared to touch anything. Hser says they weren't sure how to operate the shower. Once they figured it out, they cleaned up thoroughly afterward. “I folded [the towel] really nicely,” Hser says now, laughing. “We cleaned all the water." In the morning they made up the beds very carefully.

Then Hser flew to Charlottesville, Virginia. His parents and brother joined him there a few months later.

The International Rescue Committee, a major refugee organization based in the US, helps many people resettle in Charlottesville. Hser’s brother, Ehney Moo, says there was a kind of refugee lunch table at his high school.

“We just talk different language,” Moo says. “It’s amazing. Somebody from Iraq, somebody from Tibet or China or Burma or Thailand. A lot of people sit together. Even if we speak English, sometimes we have a confusion. ‘What do you say? What do you say?’ Sometimes we make fun to each other’s language.”

Moo had learned a lot more English when photographer Stabile came to see the family in Charlottesville two years ago. Stabile was on the second leg of the "Refugee Hotel" book project. Along with Juliet Linderman, he reconnected with people he’d photographed on their first nights. Linderman gathered oral histories from many of them, which are paired with Stabile’s photos in the book and exhibit.

After spending so much time learning about the lives of different refugees, Linderman and Stabile are conflicted about the process. On the one hand, as Linderman says, “Most everyone that I talked to was so grateful to be in the United States because they were finally in a place where, for the most part, they feel safe, they feel free from fear. They don’t have to be afraid they’ll be forced to flee where they’re living.”

But Stabile said they found deeper scars, and that those became part of the focus of his work. “I think we undervalue the difficulties, especially psychological and existential difficulties, that arise when you’re displaced,” Stabile says. “Displacement is a wound that doesn’t heal really that easily. Actually, I think it doesn’t heal at all. I was more interested in seeing how they deal with that.”

Ehney Hser told me that he finds it hard to describe his nationality. His parents and language are from Burma, but he has never been there. He spent most of his life in a refugee camp in Thailand, but he doesn’t speak Thai. And he still isn’t fully comfortable calling himself American, either.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!