Why Political Cartoons Make People So Mad

Victor Navasky, The Art of Controversy,

If you’re mad about something on TV, in a magazine or even a radio program like The World, you can write or email a letter to the editor, or make a Facebook comment, Tweet about it, or call in.

But if you’re the subject of a political cartoon or caricature and you disagree with it, what do you do?

We live in the age of the internet.

So it’s out there.

Forever.

Long-time editor and publisher of The Nation Victor Navasky thinks that sense of helplessness has something to do with why political cartoons can be so powerful.

Navasky spent decades at the helm of The Nation, the so-called “the flagship of the left,” so he was used to rabid debates over the issues of the day.

But he says there was only one time during his years at the magazine that the staff actually revolted.

It was 1984 and the magazine was about to go to press. The entire staff of The Nation – save Navasky – walked into his office with a signed petition demanding that something not be published. That something was not an article but a cartoon about Henry Kissinger drawn by the celebrated caricaturist David Levine.

The cartoon showed Kissinger on top, the world on bottom in the form of a woman with a globe where her face would’ve been.

“Kissinger was, in the worlds of David Levine, ‘screwing the world’ under an American flag blanket,” says Navasky. He listened to all the arguments against it, that it was sexist, but Navasky published it anyway.

Twenty years later Navasky witnessed the Mohammed cartoon controversy when a Danish newspaper published 12 cartoons depicting the Prophet. Riots ensued in several Muslim countries. There were 200 reported deaths, attacks on Danish embassies and boycotts.

Navasky remembers one cartoon in particular that French satirist Plantu drew in response to the controversy. “It showed an artist’s hand and his pen and he was writing over and over, ‘I must not draw Mohammed’ ‘I must not draw Mohammed,'” says Navasky. “He says it a hundred times and by the time he’s finished, his sentences have drawn Mohammed.”

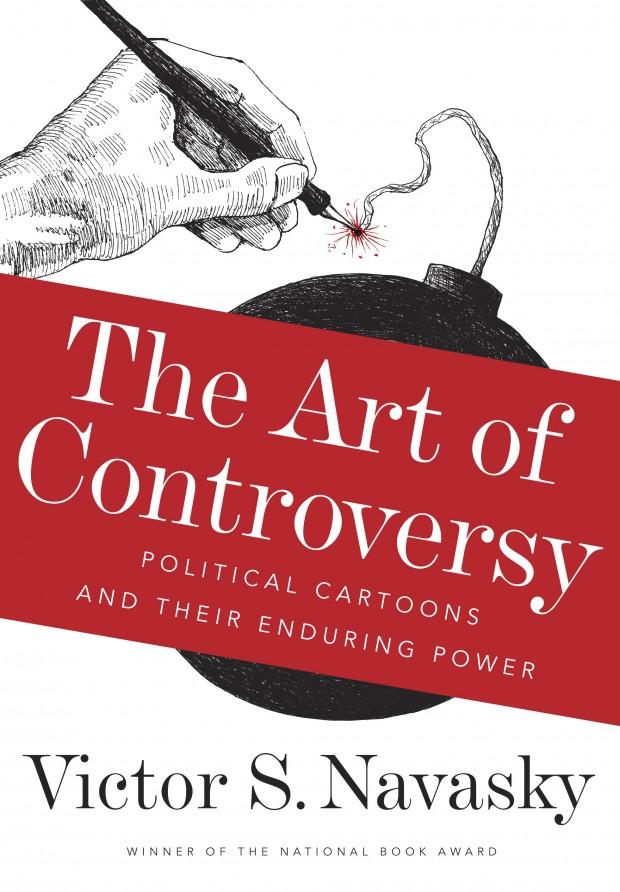

Navasky began wondering what was it about cartoons and caricature that could incite people to violence. His new book: “The Art of Controversy: Political Cartoons and Their Enduring Power” attempts to answer that.

The book shows, among other things, that political leaders have been raging about their depictions in cartoons since at least the time of Napoleon.

Napoleon, by the way, was furious with English caricaturist James Gillray, saying, that he did more than all the armies in Europe to bring me down.

Navasky introduces us to a selection of political cartoonists from the 18th century to the present who have incited the wrath of the powerful. Their fates varied.

Some were left alone. Others were pressured, occasionally sued, some beaten, and a few murdered.

David Low is a well-known caricaturist who made his career in Britain. Navasky says his cartoons about Hitler during the 1930s and ’40s made the Nazi leader apoplectic. After the war, Low’s name was found on Hitler’s death list. Navasky believes it was how Low portrayed Hitler that made him so mad. “In one cartoon, Low drew Hitler as a spoiled brat playing with blocks, each block representing a European country. Low once explained that the reason he thought that Hitler and most dictators got upset is because they want to be thought of as mad men who can destroy lives. What they don’t want to be thought of is as an ass.”

Navasky says cartoons and caricature are by definition exaggerations that usually focus on physical features. And that gives them staying power.

People remember them.

Navasky points out that the only German condemned to death at Nuremberg who was not part of the Nazi high command was Julius Streicher, the publisher of the anti-semitic newspaper, Der Stürmer. The tabloid was best known for its grotesque antisemitic caricatures. “The power of Der Sturmer came from those cartoons”, says Navasky. “The covers were displayed on the equivalent of newsstands throughout the city during those years and established the image of the Jew.” Navasky believes that’s why Julius Streicher was condemned to death.

Studying the history of political cartoons has humbled Navasky. He’s been a free speech champion his entire life and that includes cartoons. But now he realizes that some images can be too powerful because you can’t control how they’re they’re interpreted.

When he started “The Art of Controversy”, Navasky assumed he’d include those Danish Mohammed cartoons. But after talking with his publisher, he conceded it was a good idea to leave them out. Navasky realized it wasn’t worth putting people at risk.