Official kilogram has put on a little weight

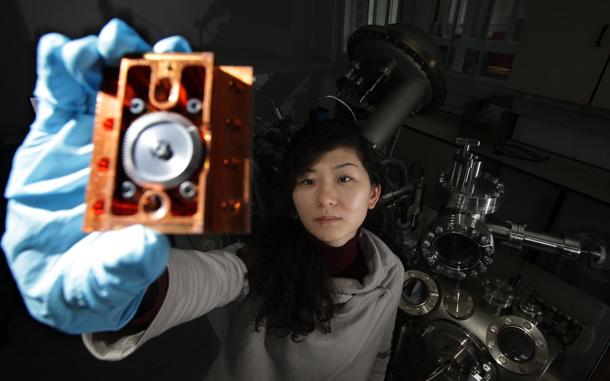

Naoka Sano examines a platinum alloy kilogram that has been cleaned by the ozone wash, to remove years of accumulated dirt. (Photo: Newcastle United)

If you’re worried you put on a few kilos over the holiday season, you aren’t alone.

Scientists at the University of Newcastle in the United Kingdom say the standard kilogram, the official determiner of weight, itself is getting a little pudgy as well.

Scientists at Newcastle have discovered the original kilogram standard is ever-so-slightly heavier than it should be. Peter Cumpson, a professor of mechanical engineering, says the surface of the official kilogram has gained weight.

The official device is a cylinder of an alloy of platinum and iridium made in the late 19th century. Back then, it was common for weights to be defined by an official item. A meter, for example, was defined by a physical artifact. Now, however, a meter is defined by wavelengths of light.

In fact, the kilogram is the only measurement still officially defined by an artifact.

“To count a standard of mass, you would have to count a lot of atoms, orders of magnitude more atoms (than wavelengths of light),” Cumpson said. “And that’s just really beyond any counting scheme, electronic or otherwise that we’ve got.”

Long-term, the goal is to convert the official standard of weight to a non-physical measurement, but that’s been impossible so far, he added.

Of course, it’s hard to be sure that the physical weight is gaining weight, because by definition it is the weight of a kilogram.

“What we’ve done is to take samples of platinum iridium alloys and place them in similar environments in similar laboratories, in fact in the same laboratory in some cases, and the result is that you pick up two kinds of contamination,” Cumpson explained. “And we think those two kinds must be present on at least a good fraction of the national standard prototypes which are held by all of the developed countries.”

The first type of contamination is fairly simple: dirt. But the other kind is a bit more exotic: mercury.

“In these laboratories where these kilograms are kept, often the scientists have to make careful measurements of temperature and pressure. Until recently it has all been done using mercury thermometers or barometers,” he said.

So, over time, the theory goes, some of those measuring devices broke and became mercury vapor that eventually settled on the weights. Mercury reacts easily with platinum and, Cumpson said, quickly forms a coating on the kilogram artifact.

All told, he added, these contaminants have added 10s of micograms, if not 100 micrograms, to the official weight of the kilogram.

“It’s very tiny. But there are one or two applications where it probably really is important to maintain something like that degree of accuracy,” Cumpson explained. “In particular, things like nuclear materials, (it’s) very important to weigh them very accurately, so you can make absolutely certain that none of it has gone astray enroute.”

So scientists are trying to figure out how to put the kilogram on a diet. But, as most of us can probably relate to, it’s tougher than it sounds. The dirt can probably be removed through a use of ultraviolet light and ozone gas.

But the mercury, because of how long it’s been on the weight, is likely staying there indefinitely.