Mohammed Fairouz’s Musical Tribute to the Fallen of Tahrir Square

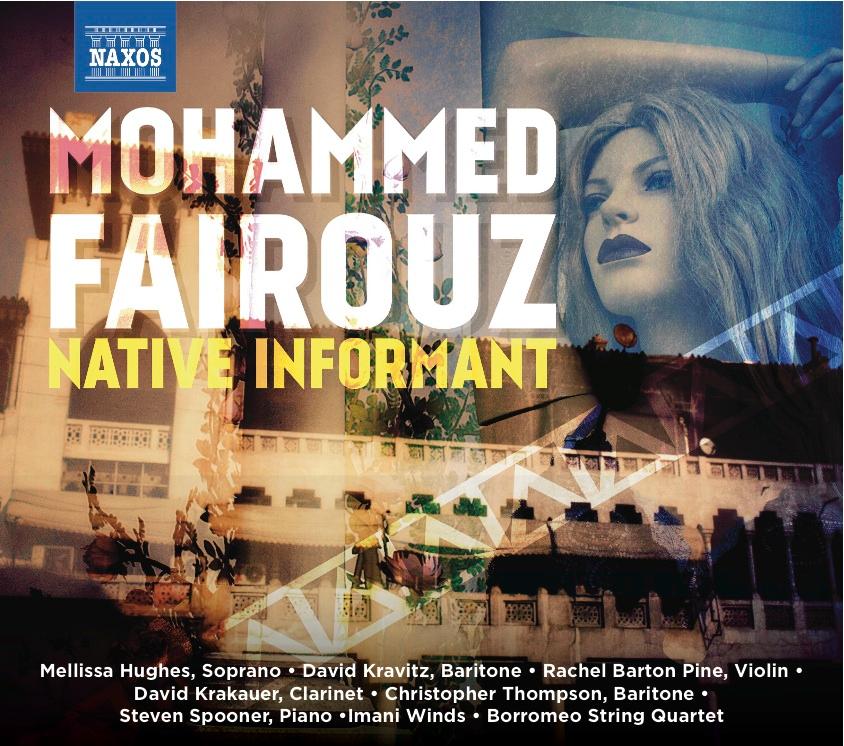

Mohammed Fairouz’s “Native Informant”.

Last year, on the first anniversary of Egypt’s uprising, we featured music by Arab-American composer Mohammed Fairouz.

It was a concerto called “Tahrir for Clarinet and Orchestra.”

And it was inspired by the gathering of protesters in Tahrir Square. In “Tahrir,” you can hear a sense of fiery revolt and hope. But Fairouz says that hope also came with angst.

After hundreds of protesters were killed in Cairo in the 2011 uprising, Fairouz began writing music for the people who had lost their lives.

“There were very personal stories that were articulated in the square,” he said. “People died. They gave up their lives. And there were tragic stories, when the regime in Egypt in its last breath of life resorted to killing people. They’re not just revolutionary icons. They’re people’s sons and daughters. They’re people’s mothers and fathers. They’re real people. They’re family members. So there were many intimate stories to be told.”

When he received a commission from violinist Rachel Barton Pine for a solo piece, Fairouz dedicated one movement of the suite to the victims.

It’s called “For Egypt.”

Mohammed Fairouz says it’s an intimate letter to the men and women who fell in the uprisings; a lamentation.

“It runs the gamut between loneliness, desperation, anxiety, despair, and even a certain amount of hope,” he said. “It captures all of those elements of dealing with death, and there’s an underlying, eerie serenity to the music. But it is very definitely a piece that tries to move beyond treating these people as a cause, and treats them as human beings. These are human losses. It looks beyond the political, to the realm of the human.”

Fairouz says the violin has existed in the Arab culture for thousands of years and is particularly well suited to this musical tribute.

“The violin has this tremendous ability to imitate the human voice,” Fairouz said.

At one point in the piece, the melody becomes particularly plaintive and inflections of the Arabic melodic scale —or Maqam— can be heard in bent notes. Fairouz meant for this moment to be a plea.

“You can almost imagine a mother or a father imploring their child not to go out into the square,” he said, “saying: ‘you’ll not be safe.’ But young people have the idealism to say ‘we want to change, we can’t live in an un-free world for ever, we have to change our society,’ and they go out, and something terrible happens to them, as really did happen to so many young people and old people, and people in the square. They were murdered.”

In the middle of the piece, the music crescendos and gets more intense, seeming almost angry and defiant.

“There’s a sense of ‘how could we let this happen to our own people?’,” said Fairouz. “And in a way, it’s all of these complex emotions that I wanted to capture in this movement ‘For Egypt’ that comment strongly on the role of the artist in this political environment, because we have a tremendous ability I think, and an advantage, especially in music, in that we can look beyond, cut through to the socio-political, right through to the human level.”

Toward the end, the violin solo reaches a quieter mood.

“It winds down, I think, into a place of serenity and acceptance,” said Fairouz, “and to some degree, of hopefulness that, in the end, perhaps all of those people who gave up their lives, did not do it for nothing.”

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!