Mali’s last master calligrapher escapes violence in Timbuktu with ancient manuscripts in tow

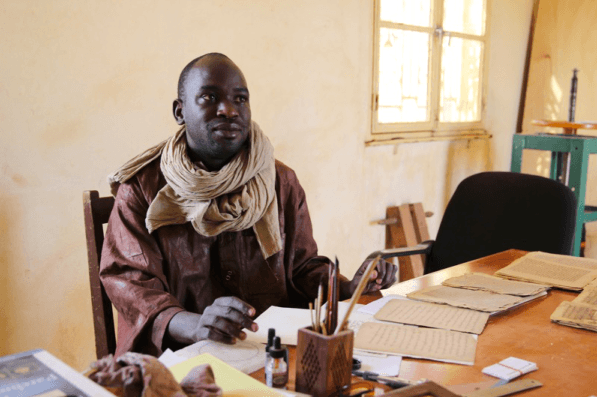

Boubacar Sadek practices the ancient art of calligraphy in Mali. He lived in Timbuktu until Islamic rebels came in and he had to flee for his safety. (Photo by Nigel Collins.)

Boubacar Sadek is believed to be the last remaining master calligrapher in Mali.

He fled Timbuktu with rare documents and now makes a living in the nation’s capital, Bamako, copying old manuscripts for posterity, as well as selling hand-made replicas to tourists.

He sits hunched over a simple table, a pen fashioned from bamboo in his hand, a modern master of an ancient craft.

He dips his pen into ink made from age-old ingredients — charcoal, powdered stone and Arabic gum, and copies the delicate lettering from parchments that are centuries old.

Sadek has carried out this painstaking work since he was a young man.

“My uncle was a master of calligraphy,” Sadek said. “It started to interest me. Each time I tried it, I loved it more and more. I wanted have a calligraphy workshop of my own.”

There was a time when calligraphers were held in the highest regard. That was back in the 15th and 16th centuries, when Timbuktu was a center of Islamic scholarship and culture.

Many manuscripts, covering subjects as diverse as medicine, astronomy, literature, law and, of course, religion, were brought to the city in camel caravans by scholars from faraway places like Persia and Baghdad.

But Timbuktu began a long decline when Morocco invaded in 1591.

The manuscripts survived that — but Sadek was worried they wouldn’t survive the jihadist invaders who showed up last year.

“In Timbuktu we had never known a situation like this – war,” Sadek said. “We only saw it on television in other countries. Everyone panicked, the people started to leave. So I brought everything to Bamako.”

He packed up delicate and crumbling manuscripts that had been in his family for hundreds of years, prompted by what he saw the militants doing.

“Destroy people’s business, anything they wanted to,” he said. “People were scared, so they started to leave.”

Sadek wasn’t the only one to go to extraordinary lengths to protect Timbuktu’s trove of manuscripts. Others hid them away in caves, or spirited them out of the city.

Now, Sadek practices his craft in a makeshift studio that sits beside a field strewn with garbage in Bamako.

He revels in the exacting nature of his task, describing how he learned to use thread to mark margins and straight lines on paper made of rice.

He’s relieved to know most of the manuscripts from his hometown survived, but he sees another threat. No one else in Mali knows how to do this anymore.

He wants the government to get involved to help interest a new generation in this old and storied calling.

“I’m proud of my craft and will continue with it,” Sadek said. “In the city of Timbuktu … these manuscripts are our rich legacy: The stories, the history, theology, geography. These are the treasures of Timbuktu.”

In his flowing robes and scarf, he turns once more to the frail papers laid out before him, recreating their elegance with each stroke of his pen.

At this moment, Sadek seems a portrait of tranquility having made his escape from violence and war.