Fidel Castro: Immortal until proven otherwise

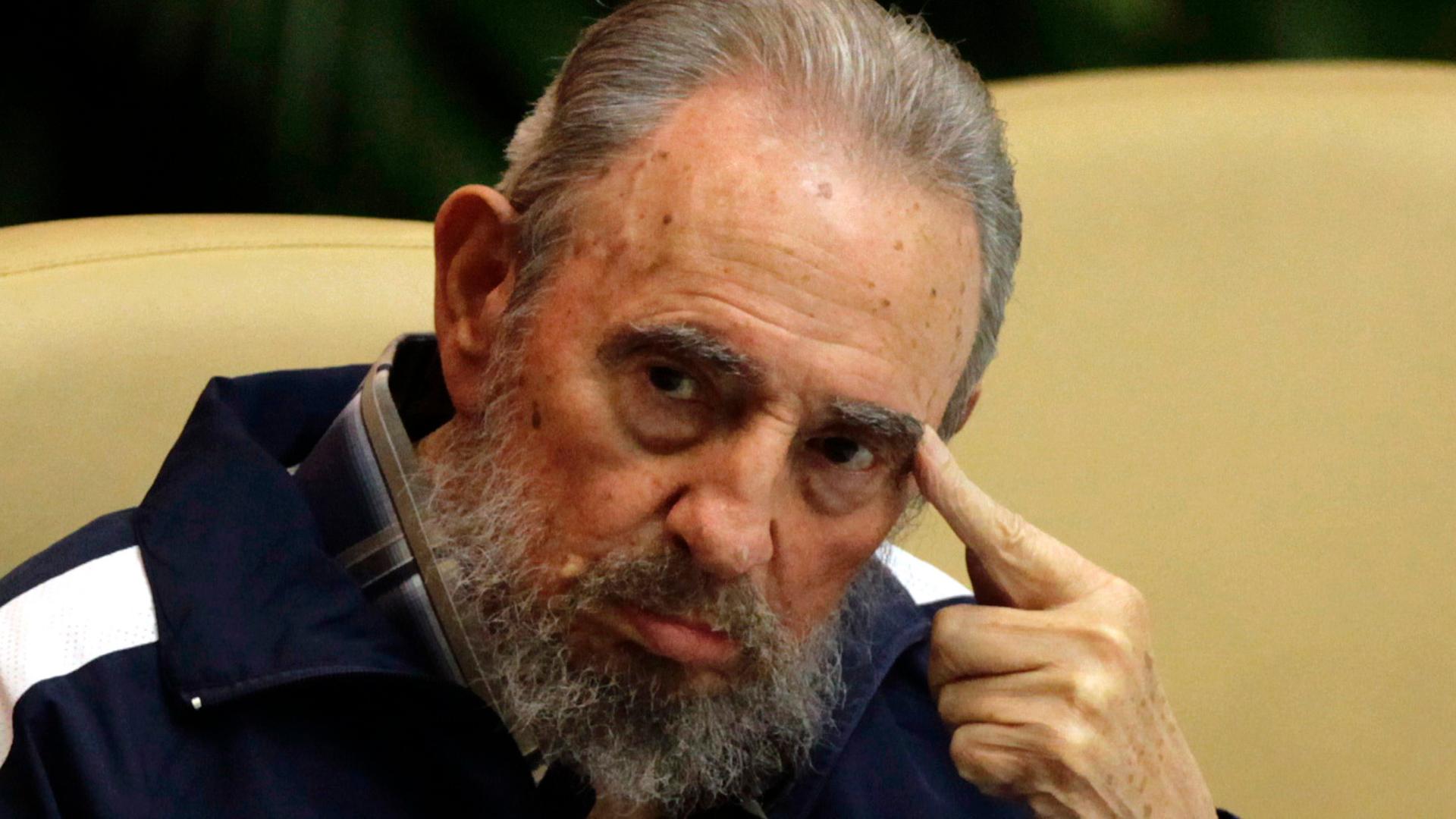

Former Cuban leader Fidel Castro attends the closing ceremony of the sixth Cuban Communist Party congress in Havana April, 2011.

This is an old joke among Cuban exiles in Miami. And it rings true, once again, now that rumors of Castro’s imminent death have been disproven by the retired revolutionary’s appearance on television this week. Some would say Castro’s got nine lives. I’d say he’s got many more.

The first time I saw Fidel Castro he was already in his twilight. Or so it seemed. It was December, 2000. I’d flown down to Panama City to cover the 10th annual Ibero-American Summit. The summit is a chance for the heads of state from Spain, Andorra and 20 Latin American nations to speak solemnly about their commitments to democracy and equality. And then there was Castro.

He was the guy I was focused on, the man most likely to make this top-shelf chat-fest interesting. Before the talks even began I made my way to the front of a luxury hotel where he was to be staying. There, I joined a gaggle of several dozen other reporters who’d had the same idea. We all stood crammed together behind a police cordon. Like Beliebers, but with microphones and pens.

After an eternity El Comandante’s motorcade of black, four-by-four vehicles rolled up the hotel drive. A hundred yards before they reached us Cuban secret service agents swung open their doors. They were impeccably dressed, as presidential details always are, in black suits and dark sunglasses. They hung out on the runners of their SUVs, each one as serious and inscrutable as the next, scanning the premises, and us.

The vehicles stopped in unison. With their tinted windows it was impossible to tell which one contained the bearded revolutionary-cum-dictator who was, in the pre-9/11 world, arguably the United States’ most vexing and indomitable enemy and against whom President Bush would initially focus his simplistic and insecure foreign policy.

A green leg appeared from one of the four-by-fours. Castro stepped down clumsily from his vehicle as his security flanked him. He was dressed in his traditional military garb, but his face was more ashen, his beard thinner and wilder and whiter than I’d imagined. It was thrilling to see this icon up close, but I was also disappointed.

He walked quickly but with the unmistakably shaky gait of the aged. Agents guided him by the arms like nurses at an old folks home. As he passed us the reporters shouted questions and snapped photos. Castro stopped for a moment, right in front of me, and raised his eyebrows in mock surprise: Are you all here to see me? He smiled at me ironically but didn’t speak. Then his muscle was ushering him inside.

My mostly Latino colleagues in the press scrum shook their heads and murmured to each other sadly about how El Comandante was getting on, how he’d lost much of his stature — even that he was losing his mind. I figured they were just sore that Castro had snubbed us after that two-hour wait. But the next day Castro pulled a stunt that got me thinking that my colleagues had been right: the President of the Cuban Council of State and Council of Ministers was losing his marbles.

The summit was underway. Heads of state were outlining how they might collectively fight poverty, improve education, eradicate corruption and otherwise dismantle their largely feudal economic structures they liked to call free market democracies. At some point Cuban press officials began quietly circulating the word that Castro himself wanted to see the foreign press — and within the hour. It was urgent.

Less than 30 minutes later they led us through an elaborate security check in an otherwise unused wing of the summit hall. We were physically searched, then told to leave our gear on the floor and ushered into a another room as sniffer dogs padded past us to snuffle for explosives. The Cubans then had us set up in yet another conference room. We aimed our microphones and cameras at a long table with a podium at its center.

Soon enough President Castro came out, unaccompanied, dressed now in a loose fitting business suit. He held in his hands an envelope, and as he waited to speak aides moved among us also handing out envelopes. I opened mine. In it was a single photocopied photograph. Beneath it read the name Luis Clemente Faustino Posada Carriles.

Posada Carriles was a Cuban-born Venezuelan, an anti-communist militant and former CIA operative who’d been trying to kill Castro or otherwise derail his government for decades. In 1976 he was convicted in absentia in Cuba for his involvement in the bombing of a Cubana Airlines passenger jet en route from Barbados to Kingston. The plane had been carrying 73 passengers, including Cuba’s mostly teenaged national fencing team. Nobody survived the crash. Until 9/11 it was the deadliest attack on a passenger jet in the Americas. Castro began to speak.

“If any of you see this man — this terrorist — here in Panama,” he said, his voice at first cracking and weak, “I would ask you to call the authorities immediately. We have reason to believe he may be here.” He arched his bushy eyebrows. “With plans to assassinate me during this summit.”

The reporters in the room rolled their eyes. In recent years Castro had taken to talking often, and at length, about the hundreds of alleged plots to kill him. By the time of the 10th Ibero-American Summit the Cuban government had documented what it claimed were more than 600 attempts on Castro’s life. Cuba’s interior ministry even ran a museum dedicated to the subject along Havana’s 5th Avenue in the ritzy Miramar neighborhood. Whether the number was accurate, you couldn’t help but feel that Castro was overplaying the matter now. Today’s ‘urgent’ press conference, called with such haste, was turning out to be a pretext to stage an animated but paranoid-sounding diatribe against unseen enemies.

“There he goes again,” a cameraman whispered to me as Fidel, ranting now, went on about how he and the revolution had survived for four decades despite so many US-backed attempts to take him out. As he grew more and more excited the words seemed almost to slur out of his mouth. His eyes were reddish and his jowls shook with indignation.

“What proof do you have?” asked a reporter.

Castro turned vague. “I am not the only one here,” he repeated direly, “Luis Posada Carriles is here.”

And so are 21 other heads of state, I thought to say. Get over yourself. The presser ended and we all filed back to the press room. Some among the press corps speculated that a desperate Fidel, with nothing to offer the summit politically, was seeking the limelight any way he could. It all seemed rather pathetic: a former Cold War icon, without cause or patron, adrift at the turn of a millennium as socialism and state run economies spiraled toward obsolescence.

About an hour later, as we were all milling about drinking coffee and watching speeches on giant screen televisions in the press room, a story hit the wires about the arrest of four men at a Panama City apartment. In the raid police seized about 33 pounds of C4 explosive. And Luis Posada Carriles. Apparently he’d come to Panama to do exactly what Castro had said: to blow the Cuban leader up during his upcoming address on the Summit floor.

Turns out Cuban intelligence agents, infiltrated in the anti-Castro Miami mafia, had uncovered Posada Carriles’ plot some time earlier. When the moment was right, for security reasons and for maximum political effect, they’d informed Panamanian police, who moved in and made the arrests.

So much for Castro’s supposed dementia. His semi-senile, babbling demeanor had us all thinking he’d sprung a leak. But now it was clear that El Comandante had known of Posada’s attack long before he’d gathered us together.

In fact, as Castro was urging us to be on the lookout for Posada Carriles, distributing his little ‘Most Wanted’ envelopes like Academy Award secrets, police were already inside the plotters’ hideout. The incident, I would learn over the next three years covering Cuba, was classic Castro theatre. And it contained a message that I could practically hear El Comandante whisper in my ear: I am still in control.