FDA makes confusing, conflicting statements on antibiotic use in farm animals

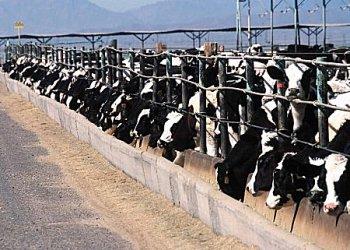

The FDA has decided to withdraw plans to regulate the most common antibiotics used in farm animals — but they’re willing to regulate a class of drugs used infrequently. (Photo from U.S. Department of Agriculture via Wikimedia Commons.)

If you’ve been following the latest moves by the Food and Drug Administration about antibiotic use on farms, there’s a good chance you’re confused.

The agency recently withdrew a promise to regulate certain antibiotics on farms, but weeks later they issued a new order to limit the use of others.

The FDA has long said it wanted to reduce the use of antibiotics on farms. Healthy livestock are given antibiotics to prevent infections and increase growth.

Some 80 percent of all antibiotics used in the United States are actually used in farm animals, said Maryn McKenna, author of “Superbug: the Fatal Menace of MRSA,”

“The vast majority of that is healthy farm animals. In other words, they’re not used to treat animals that are sick, which no one disagrees with,” McKenna said. “They’re used either to help put weight on faster so they can be sold more quickly, or they’re used to protect animals from the conditions in which they’re raised.”

Farmers say they need the antibiotics to carry out the large-scale farming that feeds much of the population, but research shows that this practice creates drug-resistant bugs that infect humans.

In December, the agency withdrew a pledge made in the 70s to regulate penicillins and tetracyclines, two of the most widely-used antibiotics on farms and to treat human diseases. Environmentalists and health activists were outraged. But this month, the FDA took an opposite step, limiting the use of some antibiotics, known as cephalosporins, in livestock.

McKenna gave the FDA measured praise for their decision to regulate one antibiotic, but said it will hardly make a difference. Cephalosporins make up less than 1 percent of the antibiotics used on farms.

“People who want to see antibiotics controlled are very frustrated that the FDA could not get this 34-year-old attempt to get the vast majority of antibiotics controlled. That they finally were essentially pushed back by Congress and industry and conceded that they were going to try voluntary reform instead,” she said.

McKenna said giving antibiotics to healthy farm animals leads to a sort of Darwin-esque battleground, where the weakest bacteria and diseases are killed, but what you’re left with in the animals is stronger bacteria that have evolved to be resistant to common antibiotic drugs.

“Then the animals are killed. Most of the bacteria being affected are in their guts and when animals are slaughtered what’s in their guts gets on their muscle meat at some point,” McKenna explained. “So, the resistant bacteria can leave the farm via the animal itself. But also, it can leave the farm via the animal’s manure.”

The manure is often left in what are known as manure lagoons, where the manure ages until it can be used as fertilizer on crops. Farm workers can be exposed to the drying manure as well, which presents the risk of bringing the bacteria home to their families.

McKenna cites MRSA, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a strain of staph bacteria that does not respond to common antibiotics, as the sort of diseases that become more common with antibiotics are over used. MRSA causes almost 19,000 deaths a year in the U.S. and is responsible for 7 million doctor and ER visits.

“Every time someone in the hospital contracts MRSA, they stay up to twice as long, their care costs up to four time as much,” she said. “Antibiotic resistance is a huge public health burden on our society.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?