Expert says laws, not funding, biggest obstacle to effective mental health treatment

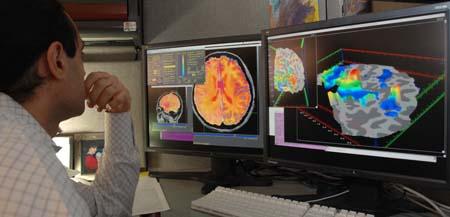

A researcher analyzes brain images from a brain imaging scan. These scans can be used alongside other tests to help doctors find the right diagnosis. (Photo by the National Institute of Mental Health.)

Calls for improved mental health care in the United States have grown larger and louder following the tragic school shooting in Newtown, Conn.

But even with a national push, some say the biggest obstacle to improvements isn’t financial.

Dr. E Fuller Torrey, executive director of the Stanley Medical Research Institute and founder of the Treatment Advocacy Center in Washington D.C., says in the U.S. about 7.7 million people have a severe mental illness — about half of them going untreated. The extreme acts seen in the Aurora, Tucson and Newtown shooting could’ve been prevented, if proper treatment were available.

“These are treatable conditions (and) if we were treating these people we would not be having the number of episodes that we’re having,” he said.

These tragedies aren’t caused by a large number of people, Torrey said. Just one percent of people who are severely mentally ill will ever be traced to an act of violence.

“If we just focus on the most severely ill, those who we know have some evidence of dangerousness, those who have evidence of not taking the medications they need to stay stable, we would be doing much better,” he said.

Stigmatization of the mentally ill is a major problem, Torrey says. But these stigmas largely come from untreated people committing horrific crimes.

“Until we focus on that and actually start treating these people, it’s going to be impossible to decrease the stigmatization,” he said.

But the problem, Torrey says, isn’t necessarily one of money.

“There’s over $100 billion of federal money in the system right now to treat people with mental illnesses. The problem is it’s being spent very poorly because of the lack of leadership at the state level and also the federal level,” he said.

Right now, Torrey says, we probably have enough money to do a good job if we focused on the people who need services the most.

Though there’s still a need for more psychiatrists to focus on severely mentally ill people. Another complication is the rights of a severely mentally ill person are protected so well it’s almost impossible to treat them.

“But we’re not protecting the rights of the average citizen to be able to go to a movie theater and not be shot,” Torrey said.

Though these laws vary by state, Connecticut, which has very strict laws, would’ve made it very difficult for someone like Nancy Lanza, the mother of shooter Adam Lanza, to force her son to receive treatment. To change this, state legislatures would need to chane the laws around civil committments and make outpatient treatment more widely available.

“Which will keep that one percent on medications so that they don’t become dangerous,” Torrey said.