Despite Economic Gains, Peru’s Asparagus Boom Threatening Water Table

Peru has become one of the leading exporters of asparagus in the world. (Photo: Cynthia Graber)

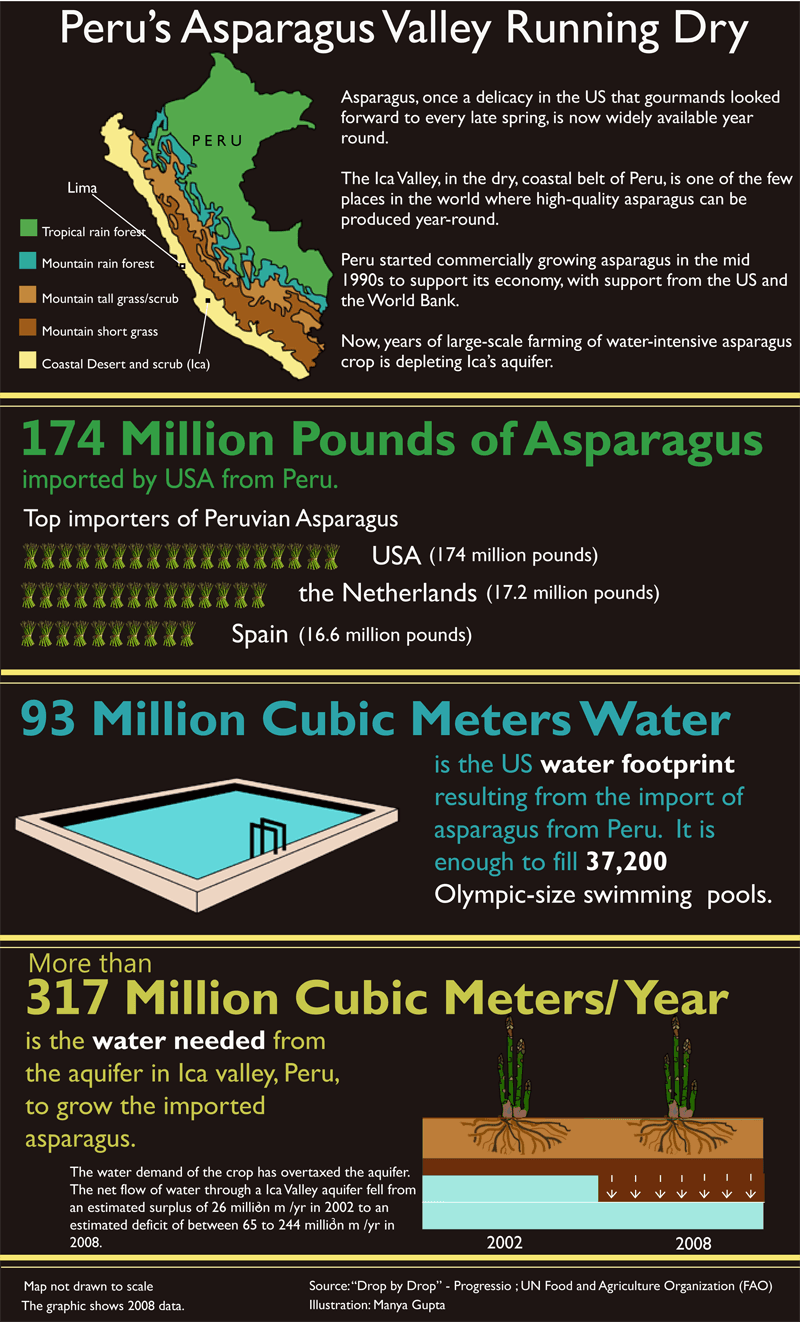

Peru has recently become the world's number one exporter of asparagus to places including Europe and the US. The boom there has pumped a lot of money into the economy, but it's also pumped out a lot of water.

Ica is a small, modest city near the Peruvian coast. But on a recent night, the city's downtown plaza is hopping, including a small religious parade.

The bustle is largely due to asparagus. Ica is Peru's asparagus capital. And the overseas demand for the long green spears has turned the place into a boomtown.

Locals say unemployment is near zero. Poverty has been cut in half. And there are unheard of amenities.

"There are now movie theaters as of only four or five years ago," says Cecilia Blume. "And another thing that's super important to me is the social revolution. There isn't childhood malnutrition. Because in Ica, there's work now for women – in agricultural packing."

Blume grew up here and now runs a consulting company that works with asparagus exporters. And she and others in the business chalk almost all of this progress up to asparagus. But the picture here in Ica isn't totally rosy.

Manuel Checa drives me straight up to the top of a sand dune high above the Ica Valley. Checa is part-owner of an agro-export group called Athos. They grow asparagus and pomegranates on about 1,200 acres of land.

He stops the car and points to some of the blocks of green that stretch out below us.

"This asparagus is 17 years old," Checa says, "and it has produced very well. But now, we've killed 20 percent of our asparagus, and this year we're killing 20 percent more."

Checa's company is pulling back from asparagus, after two decades of growing more and more of it.

"It's causing a water problem," he says. "We have to change crops.”

That's because asparagus is a thirsty crop. And this part of Peru, along the coast, is basically a desert. The climate is great for farming, but the only water here comes when rains high up in the Andes wash through on their way to the sea.

That feeds local rivers and replenishes underground aquifers. There's always been agriculture along these rivers. But never like today.

"The agro-exporters starting from 1995 intensively were overdrafting the aquifer, pumping water up and out," said David Bayer, a local water activist who first came to Peru in 1964.

He says the Peruvian government, with the support of the US and the World Bank, pushed asparagus cultivation for export, irrigated with water pumped up from the aquifer, for only the cost of building and operating wells. Basically free water.

"And they also took over the equivalent, in the case of the Ica Valley, the equivalent of virtually 40 percent, 45 percent of the land," Bayer says.

Over time, all that irrigation has caused the aquifer to drop lower and lower. That's made it tough going for some bigger growers like Athos. And it's become even tougher for small-scale farmers.

Dominga Rosario owns a patch of land in a neighborhood on the outskirts of Ica. She's one of thousands of local residents here who farm mostly to feed their families.

She points out her corn, mango, avocado – they're a little yellow right now. She'll get a decent crop, Rosario says, but "you have to irrigate more. You have to invest more."

That's because as the aquifer has dropped, the soil above it has become drier. But irrigation can be expensive, especially when farmers have to keep digging deeper and deeper wells. Some can't afford it. And they've abandoned their crops. The city of Ica's municipal drinking water supply could even be at risk.

"I think there needs to be a solution as soon as possible," Rosario says. "Because these companies, they're preying on the aquifer. And when the aquifer dries up, our future will be uncertain!"

The situation has gotten so dire that it's set off a scramble for solutions. For some, the answer to the water shortage is simple: just get more water.

Alfredo Sotil manages a commission that represents big agro-exporters here. He says that in the rainy season, as much as half the water running off the mountains flows into the sea. He and his colleagues want to capture that runoff behind new dams. "We're interested in taking water and transferring it here, to continue generating this development," Sotil says.

The dams could have the added benefit of generating electricity. But huge dams and water diversions are expensive, and they can cause their own environmental problems. That's why others here are focusing not on getting more water but on using less.

Miguel Betín grows asparagus and pomegranates on a farm close to the Ica Valley. He recently installed a new, super-high-tech drip irrigation system designed by an Israeli expat who lives nearby.

"It works better than what we thought," Betín says.

"What do you mean?" I asked.

"We were thinking we were going to save 40 percent water in the first year, and we saved 70," he says.

Betín says his asparagus is just as good as the crop grown with conventional drip irrigation. And he says if the other growers in the region copy him, it could make a huge difference.

"If only the asparagus growers change, you'd save like 70 million cubic meters a year. So you have a big part of the problem solved there," he says.

As for activist David Bayer, he thinks more farmers should follow the example of Manuel Checa: just stop growing water-hungry crops like asparagus. Or at least cut back on them. And he thinks some land should be taken out of production altogether for a while, to let the aquifer recharge.

Of course most growers aren't interested in killing their golden cash crop. And the Peruvian government? It's taken halting steps toward addressing the water crisis here. But some Peruvians say big changes may only come through pressure from a more formidable force: international consumers.

Stefan Bederski runs an organic farm about two hours from Ica. He says all the positive changes in agriculture in Peru recently – from better pay and working conditions to stronger environmental controls – all of them have come largely through pressure from overseas markets, especially in Europe.

"They have been really the ones who have forced the Peruvian agriculture and the companies to do the things right," Bederski says. "We do have our own local laws and national laws, but there is no force to make them happen."

Bederski thinks it might well be the same with the overuse of Peru's water, that it's the consumers overseas who will make the difference.

An international coalition of nonprofits is already trying to make that possible. They're developing water use standards for Peru and around the world that will be like fair trade standards.

They say the effort will help consumers in Europe and the US learn more about the water impact of the asparagus and other imported produce at their local store, so they can choose products that don't take a big gulp from someone else's nearly depleted cup.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!