Biologist tries to save endangered butterfly species by capturing invasive iguanas

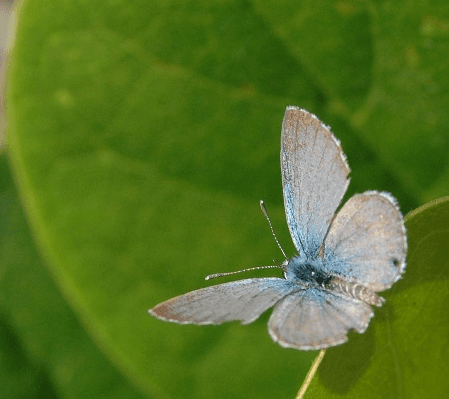

The Miami Blue Butterfly is endangered and on the verge of being lost from a combination of mother nature, bad luck, and invasive, non-native species. (Photo courtesy of Florida Park Service.)

Biologist Jim Duquesnel gets up every day to do two things, find a Miami Blue Butterfly and rid the Florida Keys of the Green Iguana.

The invasive reptile, he said, is driving the Miami Blue Butterfly to the edge of extinction. Once a thriving species on Bahia Honda island, no one has seen a Miami Blue since July 2010.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has listed the butterfly as an endangered species. Its threatened status is blamed on he invasive Green Iguana, which has no predators in the Keys. The growing population feeds on the leaves of the Nickerbean Blue plant, the same leaves where the Miami Blue lays its eggs.

See a photo gallery of Miami Blue Butterflies and Green Iguanas at hereandnow.org.

Duquesnel hunts the iguanas in hopes that if there are any of the dime-sized Miami Blues left on the island, they’ll have a chance at survival.

“As far as we know, the only population left is about 20 miles west of Key West,” Duquesnel said.

The Miami butterflies were nearly wiped out by a 1992 hurricane, but bounced back. Whether they’ll be able to bounce back this time, though, remains to be seen.

The iguanas in Bahia Honda state park come, in large part, from people who bought iguanas as pets and then decided they don’t want them any more. When they’re released in places like Bahia Honda, where there are no natural predators, they can multiply endlessly.

So Duquesnel has become their predator. But the iguanas are smart and have adapted to try and avoid him, he said.

“When I started doing this, I was able to catch naive iguanas very quickly,” Duquesnel said. “But they very quickly learned there was a wolf in sheep’s clothing here in the park. Animals don’t survive for eons by being dumb.”

When Duquesnel started, he’d see 40 to 50 iguanas a day in the park. Now he just sees a couple, in part because he’s reduced the population, but more so because they’ve grown wise to his efforts to hunt them.

The iguanas, once caught, had been adopted out to reptile rescue organizations, but the animals were so poorly adapting to captivity that they’d starve themselves to death. So now, Duquesnel said, the iguanas are euthanized.

“To try make something good come out of this whole thing, we donate the euthanized iguanas, and sometimes live ones, to research facilities, to veterinary medical schools.”

But still, even if Duquesnel can get the iguana population under control, he said the odds remain long that the Miami Blue population will rebound.