Author Ishmael Beah recounts his childhood as a boy soldier

in his 2007 memoir Long Way Gone, Ishmael Beah recalls how he was indoctrinated into war as a child soldier. (Photo courtesy of To The Best Of Our Knowledge).

In the early 1990s, Sierra Leone was divided by civil war. Ishmael Beah was only 13-years-old in 1993 when he was taken into the Sierra Leone army, given drugs, an AK-47 and ordered to kill.

Beah had already lost his entire family to the war, and had been on the run for a year. In his memoir, Beah recalled that at that time in Sierra Leone, there were so many child soldiers that no one would trust him or take him in out of fear.

“Between 12 and 13 I had lost my entire family which was my mother, father, and two brothers,” Beah said. “There was nowhere to go, nothing to do, so I found safety among the soldiers. At least I thought it was safety.”

Beah was indoctrinated into the army by being fed a steady diet of drugs and war films.

“No, I didn’t want to fight,” Beah said. “And I actually remember the first time I was given an AK-47, I could not look at it, I was trembling. But there was no choice in the situation, it was either you do this, or they’ll kill you. But after the first shooting, the first killing, the first battle, you are traumatized, you’ve lost your humanity, this becomes the life that you know.”

Beah said the violent environment child soldiers are exposed to forces them to forget their previous life.

“A lot of people did come to enjoy the killing, including me, because when you are there at that time your situation becomes so normalized,” he said. “This reality becomes what you do. You actually have a weird attachment to it and enjoy what you’re doing because you’ve lost yourself.”

After two years in the Sierra Leone army, Beah was rescued and placed in a rehabilitation center run by a UNICEF program called Children Associated with War. Beah described his transition back into society as challenging.

“After you’ve been removed from the context of war, you’re still thinking like you’re in the war,” Beah said. “We’ve developed an understanding that civilians were lesser, that if you’re not a combatant you’re lesser, and that a combatant can decide whether you live or die. This mentality was there, so when civilians spoke to us we were very upset.”

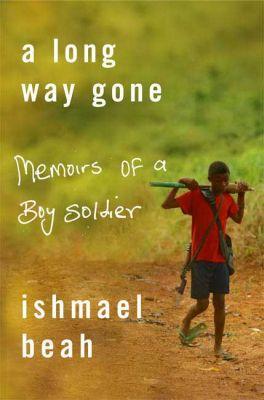

After Beah’s rehabilitation, he was able to move to the United States where he was adopted and attended high school in New York City. In 2004 he graduated from Oberlin College with a bachelor’s degree in political science. Since moving to the United States, Beah has spoken on numerous panels and joined Human Rights Watch. Beah’s books, A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier was published in 2007.

“I can put a human face to what seems so distant to a lot of people, and also remembering, even though it’s difficult, is a small price to pay,” he said.

Beah said that he was motivated to write the book to help readers comprehend the humanity and recognize the potential of child soldiers.

“(The army) uses children because they can corrupt them pretty easily, especially after they have lost everything that is dear to them,” Beah said. “So this is a very serious issue, which is one of the reasons I wrote this book. So that people can understand how (corruption) comes about, but more importantly, so that people can understand that it is possible to help these children regain their lives again.”