Academy Award-nominee Life of Pi inspired by much older book by Brazilian author

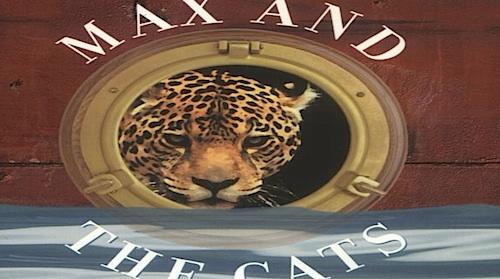

Max and the Cats, by Moacyr Scliar, was a major inspiration behind the book that became the movie Life of Pi.

A friend recommended I read The Life of Pi. Never a spoiler, she described the plot in broad strokes.

“Wait a minute,” I said. “I’ve read that.”

I hadn’t, but ever since I read The War in Bon Fim, about a certain Brazilian neighborhood during the Second World War, I had devoured everything I could find by the Brazilian physician and author, Moacyr Scliar. When I ran out of his books in English translations, I began The Centaur in the Garden in the original Portuguese, figuring it should not take me forever since I altready knew the life story of the half-horse baby of Jewish heritage born in Brazil, the ultimate outsider novel.

“Not a tiger,” I said to my friend. “It was a jaguar in the boat.”

I was remembering Scliar’s Max and the Cats, where young Max must flee pre-war Berlin just ahead of Nazis who had been set upon him — Max is Jewish — by the husband of the older woman with whom the youth has been cavorting. A shipwreck on the way to Brazil leaves Max in a dinghy with a jaguar escaped from the hold. I never considered the jaguar a reflection of Max’s inner fears, as I read in one review, never a mirror of his attempts to control the terror that struck his heart with the presence of Nazis in this world.

I thought Max and the Cats was just a terrific yarn, the jaguar the most memorable of the felines Max encounters as he grows and changes like the best of literature’s protagonists.

By 2011, when I was planning to visit Scliar in his home town of Porto Alegre, Brazil, I was aware that Pi’s author, Yann Martel, had fessed up, that he admitted he had taken his Pi from Max. Taken his Pacific from the rough Atlantic, his circling sharks from Scliar’s circling sharks, his tiger from the jaguar. I only knew because my curiosity set me on an evening’s Internet search.

With The Life of Pi, the Canadian author won the coveted Man Booker Prize, catapulting Martel to fame. The film based on the book was a nominee for the Academy Award for best picture.

Well, I thought, you can’t copyright a title, can’t trademark an idea.

“It might have been good if he had communicated, at the beginning,” Scliar’s widow said.

She said it softly, with bewilderment, but also resignation.

Martel ambiguously thanks Scliar in an author’s note for “the spark of life.” In an essay, he said he got the idea for Pi from an “indifferent” review of Max and the Cats by John Updike in the New York Times.

Updike never wrote a review of Max and the Cats, anywhere. Also, it’s difficult to believe a reader could be “indifferent” to Max, whose multi-layered story evokes a mix of emotions, where Pi might be characterized as a good, one-note read.

On Jan. 27, 2011, I fell backward down a flight of concrete stairs (don’t ask), and was forced to cancel my ticket to Brazil. Meanwhile, Scliar suffered a stroke and died from its complications.

When I reached Porto Alegre in May, in gaucho country in southern Brazil, the weather was coming into winter in the southern hemisphere. Wrapped in a scarf and hat, I traipsed the streets of Bom Fim that I felt I knew from that first book of Scliar’s I’d read, seeing again the characters scratched forever into a boy’s mind, feeling the anxiety and humor that could come only from a mature writer in control of his pen.

Eerily, the local university was presenting the history of the venerable neighborhood in a gallery exhibit, which Scliar had been curating before his stroke; it became a memorial to Porto Alegre’s most famous resident, his talk missed in local cafes, greetings missed on the streets.

A member of the Brazilian Academy of Letters in Porto Alegre, Scliar was both a storyteller and kind, always accessible public health doctor. The only author of whom I am aware whose obituary ran in both The New York Times and The Lancet, the world’s leading general medical journal, and in specialty journals in Oncology, Neurology and Infectious Diseases.

Bom Fim. In Portuguese, it means good death.

On my last day in Porto Alegre, I bought a ticket on the next morning’s bus to Montevideo, and wrote an email to Scliar’s widow expressing regret over the death of her husband. She responded, inviting me to come over, at that very moment.

Judith Scliar is a beautiful woman who married young, clearly stayed in love for all the decades, and still seemed surprised by death. I spotted a short, sweet note to “Judy” from her husband, inserted between books near the table where we sat.

It was all too fresh. She cried. Although I knew neither him nor her, I too wept at the sheer weight of her sadness.

“Come with us to the movies,” she said later.

We would go with Scliar’s best friend in life, and Judith Scliar’s best friend, to the opening of “Midnight in Paris.”

“You will see every Jew in Porto Alegre there,” she said. “We are the only ones who really get Woody Allen.”

Afterward, we sat in a cafe talking over strong Brazilian coffee until the three of them fell into a round of telling jokes, one seemingly more outrageous than the other — even though I didn’t get all the punch lines.

The previous day on Riachuelo Street, in a remarkably stuffed bookstore — upper floor tomes simply stacked as high as physics allowed, no shelves — I had found a 20-year old volume co-edited by Scliar on Jewish humor. Probably he didn’t have to go far for inspiration.

The last time I visited Porto Alegre, a year had passed. The widow had little time for a visitor. Moacyr Scliar, not well-known abroad, was at least a hero in his own land. A new annual literary prize carrying his name had been inaugurated, with a value of more than $75,000.

Judith Scliar was on her way to Rio de Janiero to open a new school named after her husband. She showed me the office where he used to write, desk cleared and otherwise streamlined because students and researchers were arriving.

In that room, Judith Scliar slowed down. She ran a finger along the desk. I told her Pi had become a movie.

She didn’t seem to hear.

“He had more books in him,” she said of her late husband. “Maybe seven or eight more books.”

Mary Jo McConahay has reported from Central America for numerous publications. She is the author of “Maya Roads, One Woman’s Journey Among the People of the Rainforest.“