Wheat Can Be Kindness and Other Political Candidates

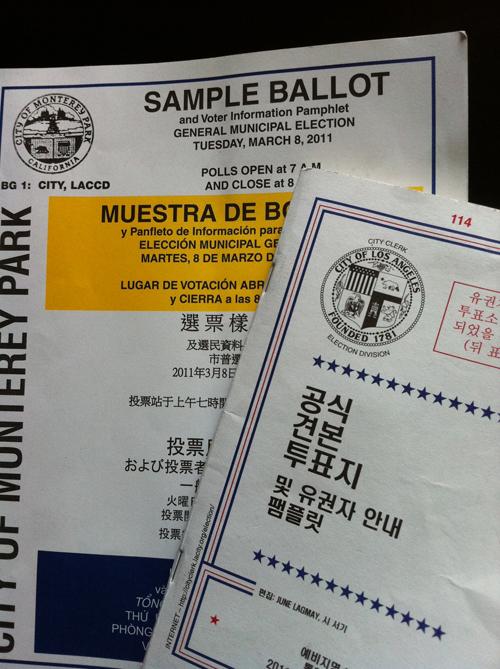

California Ballot (photo: Nina Porzucki)

by Nina Porzucki

California’s legislature is moving to regulate how political candidates’ names are translated. The state is home to the largest Asian American population in the nation. Nearly a third of Asian American voters in California are not proficient in English.

Election materials have been translated into several Asian languages for years, but the law doesn’t specify how candidates’ names should be translated.

Consider the case of Mike Eng. Five years ago he was a candidate for the California State Assembly. “When I saw how my name was spelled [on the ballot] I almost fell out of my seat,” Eng says.

Eng was running for a seat in the California assembly. About 40 percent of his district is Asian American, with sizeable communities of Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese and Korean speakers. Under federal law, election materials in Eng’s district must be translated into those four languages. So when Eng was asked if he wanted his name translated onto the ballot, he thought, “Well of course.”

Officials translated Eng’s name literally, into what in Chinese sounded like Mike Eng: 麦 å¯ æ© (or Mai Ke En) Literally, the characters mean something like “wheat can be kindness.”

When Chinese characters are strung together to create phonetic transliterations of Western names, they can sometimes turn into pretty nonsensical sayings like well, “wheat can be kindness.”

Mike Eng wasn’t so happy with a name that “doesn’t mean anything.”

As turns out Eng, who is Chinese American, also has a Chinese name that was given to him at birth by his grandparents. His Chinese name has nothing to do with wheat or kindness, but means “pride of our national day.” This was the name used by the Chinese media, the name that many voters knew him by. So Eng ended up spending the rest of his campaign telling voters “that this person that sounded like wheat in Chinese was actually me.”

Despite the confusion Eng won the election. But the situation still bothers him.

Unlike English, written Chinese is based on meaning as well as sound. You might think Eng is hung up on the fact that his ballot name meant “wheat”. But meaning is a big deal in written Chinese, says lexicographer David Prager Branner.

Characters that are used in Chinese names are also part of everyday language. “The meaning is right in your face with the Chinese writing system,” says Branner. “You can’t escape it.”

Take Branner’s name. In English, no one really thinks about what “David” means. But when he uses his Chinese name å¾·å¨ (De Wei) Branner says the meaning of the two characters (“virtuous inner strength” and “the power to awe”) is right there.

Under the Voting Rights Act, certain jurisdictions are required to provide minority language assistance. This means translated materials, ballots, signs, bilingual poll workers. But federal law is silent about name translation.

Some states regulate how names appear on the ballot in character-based languages like Chinese, but not California. In California the rules change from one jurisdiction to the next. Assembly member Mike Eng’s situation was unfortunate but by no means the most extreme example of a name change.

Some candidates may even have used this grey area of the law to gain favor with Asian American voters. In 2010, someone namedæ? æ£ å¹³(Li Zheng Ping) ran for San Francisco Superior Court Judge. Someone named Michael Nava also ran. It turned out that they were one and the same person. Michael Nava quite legally assumed the name Li Zheng Ping in some of his outreach to Chinese-American voters. Li Zheng Ping is a Chinese-sounding name, and a good one for a judicial candidate. In Chinese, it means “correct and fair.”

Assembly member Mike Eng likens the situation in California to the wild west. “If you want to say that my name means ‘giver of million of dollars in profits to local governments’ then one could list your name on the ballot that way” he says.

California State Senator Leland Yee has introduced a bill regulating how candidates’ names are translated into character-based languages.

“All of us want good sounding names that engender warmth with the Chinese vote” says Yee. “But when I think that when you do that solely for the purpose of gathering that vote and nothing else than I think it’s a little unfair.”

In 2009, an earlier version of the bill was vetoed by then Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, who declared that individual jurisdictions should decide this matter on their own. But Yee re-introduced it this year.

“If Chinese Americans think that the voting process is a sham and that politicians are trying to trick them, then they are less inclined to participate in the electoral process” says Yee.

Dean Logan, the Registrar of Voters in Los Angeles County, says under the proposed law, he would have to decide on which translations to use in LA County. He’s uncomfortable with that.

“You could ultimately have someone challenge that in court which further delays the process,” says Logan.

It’s somewhat surprising that California, with its large Asian American population, lags behind other states like New York where policy about candidate’s names has been in place for well over a decade. But that may change in soon. Assembly member Mike Eng certainly hopes so.

“Your name is your identity. Your name is your heritage,” says Eng. He looks forward to the day “when we can have a ballot that does truly reflect the true identity of those that are running because that’s better democracy.”