The Multiplier Effect: Driving Haiti’s recovery by spending aid dollars locally

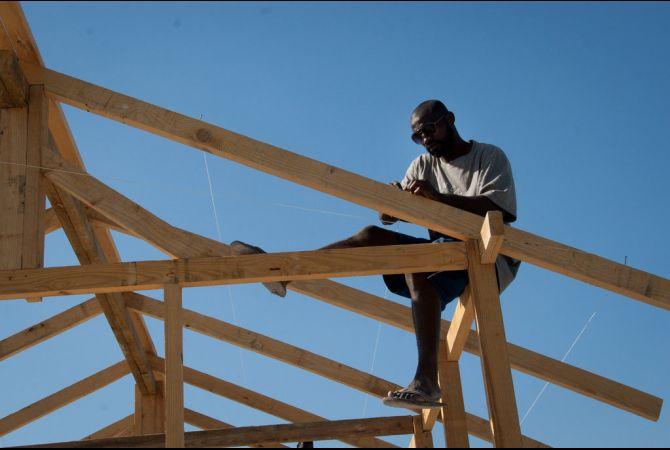

A man works to build a church roof using locally purchased, foreign-imported wood in the Neret neighborhood of Port-au-Prince.

PORT-AU-PRINCE, Haiti — Just days after a cholera epidemic began infecting thousands of Haitians in October 2010, Salim Loxley received a phone call at his desk in Port-au-Prince from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), one of the largest-spending organizations operating in the post-earthquake nation.

“We need 4.5 million bars of soap by Friday,” said the man on the other end, anxious to distribute the soap to Haitians who were living in unsanitary displacement camps and vulnerable to the highly infectious disease.

Normally such a call would go to one of UNDP’s US-based suppliers, who would truck the soap over from a warehouse in Haiti or ship it down from the States. But, as a director of entrepreneurial NGO called Building Markets at the time, Loxley had a database at his fingertips that included eleven local soap suppliers and three manufacturers who produce soap here in Haiti.

Loxley helped connect UNDP with Fritz Brandt, whose company Carribex has been producing soap, oil and other food products for local consumption in Haiti since 2004.

Carribex was able to produce and begin delivering the special type of soap UNDP needed to slow the cholera epidemic in just two days — so fast, in fact, that UNDP momentarily ran out of space to put it all.

“I started delivering in 72 hours, and finished three million bars in less than a week,” said Brandt, who also helped UNDP identify a recipe for a particular laundry soap that would be more effective than typical bar soap in killing cholera bacteria. “I had to stop delivering because they didn’t have any warehouse to put what they asked for.”

Brandt said the $252,000 soap deal, which was followed shortly by a $600,000 deal with UNICEF, marked the first time in seven years of operating his factory that one of the foreign NGOs or international bodies that spend billions of aid dollars annually on supplies and equipment had ever contracted with him.

The $10.2 billion in aid pledged to post-earthquake reconstruction in Haiti is largely bypassing the nation’s local producers and importers. Only 2.4 percent of the $205 million in aid contracts by the US government in Haiti as of September 2011 went to Haitian companies, according to an analysis by the Center on Economic and Policy Research of the Federal Procurement Database System.

Now in the final weeks of its campaign in Haiti as its own funding runs out, Building Markets is working to get the thousands of other NGOs to send more contracts to local businesses — the first time many of these businesses have had access to foreign NGO dollars.

By investing in local business, Loxley, formerly the organization’s country director, said aid dollars could have a “multiplier effect” — bringing workers into the factories and warehouses of Port-au-Prince and off the crowded streets where hundreds of thousands of vendors hawk imported soap, rice and products in an informal economy.

“You’ve got the international community coming down, the UN coming down and creating a massive economic footprint on the ground with projects, programs to deliver, humanitarian aid to deliver,” Loxley said. “[The Caribbex soap deal] is an interesting story because it tells you that there is capacity in Haiti. Buyers don’t understand what’s here, they don’t trust the organizations that are here.”

Caribbex is just one of hundreds of contracts the organization has facilitated here in Haiti. It helped a Chinese importer contract with a Haitian fishing cooperative to buy 10 tons of sea cucumbers each month. The demand created by that deal helps employ the estimated 5,000 workers from 50 different fishing outposts across Haiti.

And after the earthquake damaged a local businessman’s brand new air conditioning unit plant, Building Markets helped win the company win contracts for energy-efficient AC units for the UNDP, Haiti’s Ministry of Justice and its National Police.

*****

Building Markets (formerly Peace Divided Trust) began operating in Haiti before the January 2010 earthquake with the hopes of replicating its success getting the United Nations to contract with local companies in Afghanistan. The organization studied the UN’s activities there and found that an estimated 80 percent of aid money directed to local businesses generated local economic impact, versus 15 percent for funds that went through foreign NGOs and contractors. The US military spent $14 billion on contracting there in 2009 alone, according to Reuters.

Former commander of US forces in Afghanistan Gen. David Petraeus urged the US and other actors in his counterinsurgency strategy to “Hire Afghans first, buy Afghan products, and build Afghan capacity.”

By contracting locally, he argued, the military intervention could help strengthen Afghanistan’s stagnant economy and win the confidence of more of the Afghan people in the process. Reuters reported that 80,000 of the estimated 112,000 contractors used by the US military there currently are Afghan-operated.

Loxley said Building Markets hopes to emulate that message in Haiti. The importers and manufactures that operate here struggle to compete for large contracts by NGOs and the US government, which often ultimately go to American firms. As of September 2011, only 23 of 1537 post-earthquake contracts by the US Agency for International Development (USAID) had gone to local businesses, with nearly 40 percent awarded to Beltway contractors from D.C., Maryland and Virginia.

And according to documents obtained by the GlobalPost, USAID allocated $1.1 billion dollars in humanitarian assistance to Haiti in fiscal year 2010 through dozens of different organizations — but not a single dollar went directly to a Haitian organization or business.

“When big international organizations like the UN get tasked with responding to an earthquake, their job and their first priority is, ‘How do I respond to this crisis immediately?’” Loxley said. “They’re trying to do this as fast as possible, and they don’t have time to try to find out who are the reliable suppliers.”

But by seeking out local businesses, verifying and certifying their work, and publishing them in an online directory, Building Markets essentially does that for them.

The NGO has facilitated $32 million in contracts between Haitian companies and buyers, and more than 500 Haitian companies have already received contracts with more than 100 international organizations. The organization’s online directory now includes 3,500 Haitian businesses, one-fourth of which are in the construction sector.

The result is more foreign aid dollars going the way of companies like Carribex, which many NGOs don’t know exist or don’t believe are reliable, often deciding it’s simply easier to stick with the American companies they know.

Brandt, the owner of Carribex, said Building Markets is forming a line of communication between businesses like his and large foreign organizations that never existed previously.

“Both parties have their negative parts,” Brandt said. “We have never gone to the NGOs to tell them ‘Here we are, this is what we’re producing in case you’re interested.’ We didn’t’ make any sales approach to them. For their part, they didn’t care to ask any government entity if there was anyone here producing a particular product.”

*****

Sari Kaipainen, reconstruction manager for the NGO Finn Church Aid that designs and builds schools in Haiti, says often NGO procurement officers don’t approach Haitian businesses because of the assumption that foreign-produced products are of superior quality or because contracting locally can be more complicated.

“Dealing with Haitian businesses, in the commercial sense it’s still a very young culture,” Kaipainen said. “Things like financing and invoicing are still very basic, and we’ve been trying to help them organize that. We’re trying to help them understand that a contract is a legal document they must abide by.”

Kaipainen says the biggest challenges are ensuring the company delivers exactly what was ordered at a reasonable price.

“Sometimes prices have no reflection on reality at all, or [local companies] think ‘because you’re a foreign NGO we can charge whatever we want.’” She says Building Markets reduces that price gouging by introducing what she calls “reasonable competition” into the market.

One of the largest obstacles to Haiti’s long-term development is the lack of jobs and its inability to produce many goods or services that can infuse wealth into its ailing economy. Studies over the past decade have estimated Haiti’s unemployment as high as 70 percent — a figure many say is kept high by Haiti’s reliance on foreign-manufactured goods.

“Not only was I giving them the soap they really needed in the timing they wanted, but also the deal would help me keep my [workers],” Brandt said.

Haiti’s government has often called on NGOs to spend more aid dollars on contracts with Haitian companies.

“We also want to encourage NGOs to simplify their procurement procedures to facilitate greater participation with local suppliers,” said Marie Pascale Theodate, member of the cabinet of Haiti’s Ministry of Commerce and Industry in an April speech commending female entrepreneurs in Building Markets’ program. “The course was clearly set at the Ministry on the need to free the country from its dependence on international assistance and boost growth through coherent public policies.”

But having nearly exhausted its three-year grant from the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), Building Markets communications officer David Einhorn said the organization is planning to end its Haiti operation at the end of June.

We applied for additional funding and it wasn’t available,” Einhorn said. “Thanks to CIDA we were able to facilitate a lot of local transactions in Haiti. These organizations can’t fund projects forever — we’re grateful for the support they’ve given us.”

Einhorn said Building Markets is in the process of transferring its online directory and some of its other services over to Haiti’s Ministry of Commerce and Industry, which has been collaborating closely with the organization. For months, Building Markets employees have worked at the Ministry office to help Haiti’s government make it easier for foreign organizations to contract with Haitian businesses.

“This was the original intent,” said Einhorn of the hand-over. “We’ve tried to plant a seed of this idea here, and they’ve received it very enthusiastically.”

“A lot of NGOs are pulling out of Haiti now,” he added. “We’ve helped Haiti through a difficult time and we believe that this kind of project could continue to help Haiti — the need is still there.”

This story is presented by The GroundTruth Project.