‘Oppenheimer’ film ‘fails’ to show devastation of atom bombs in postwar Japan, critics say

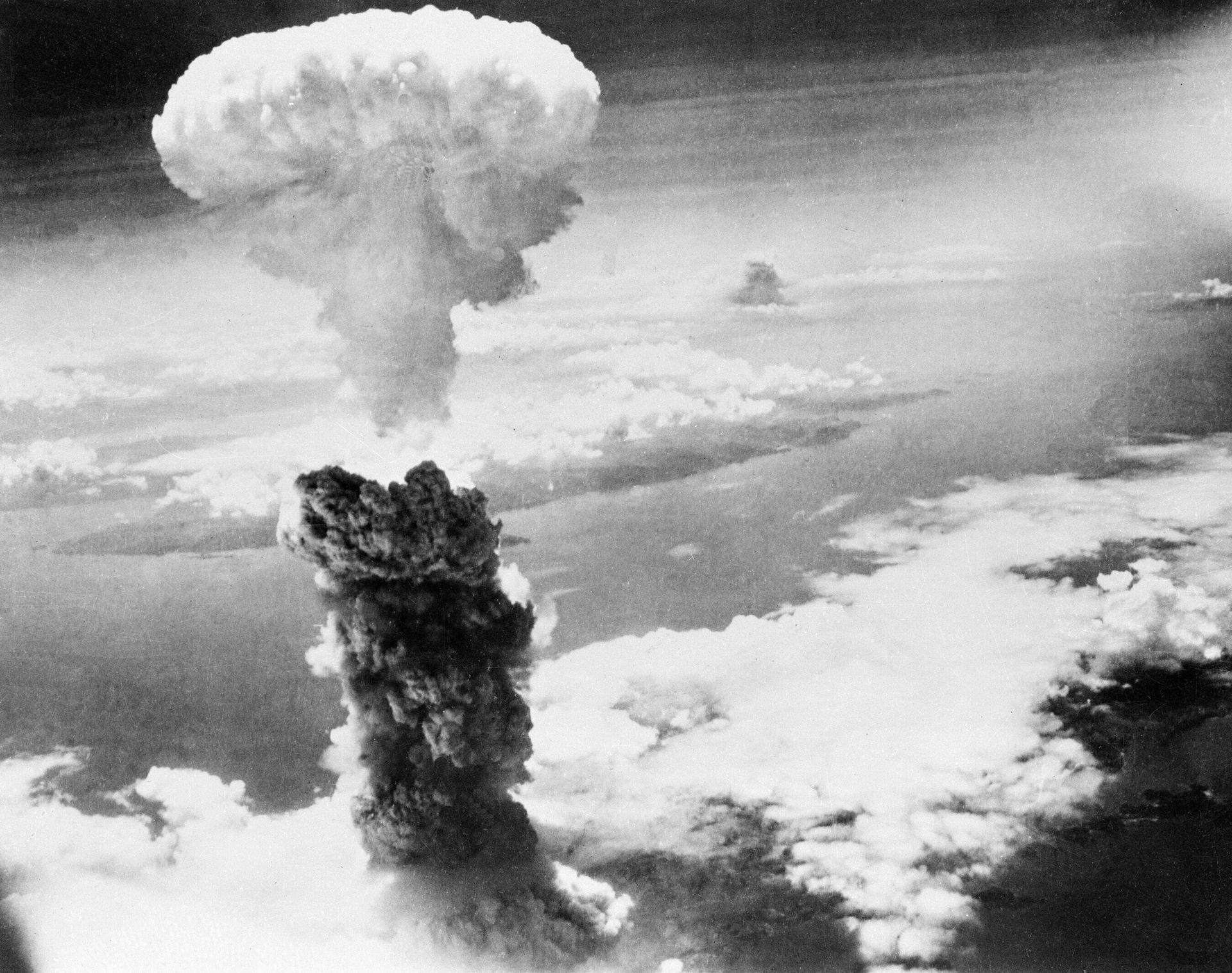

The United States detonated atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August of 1945.

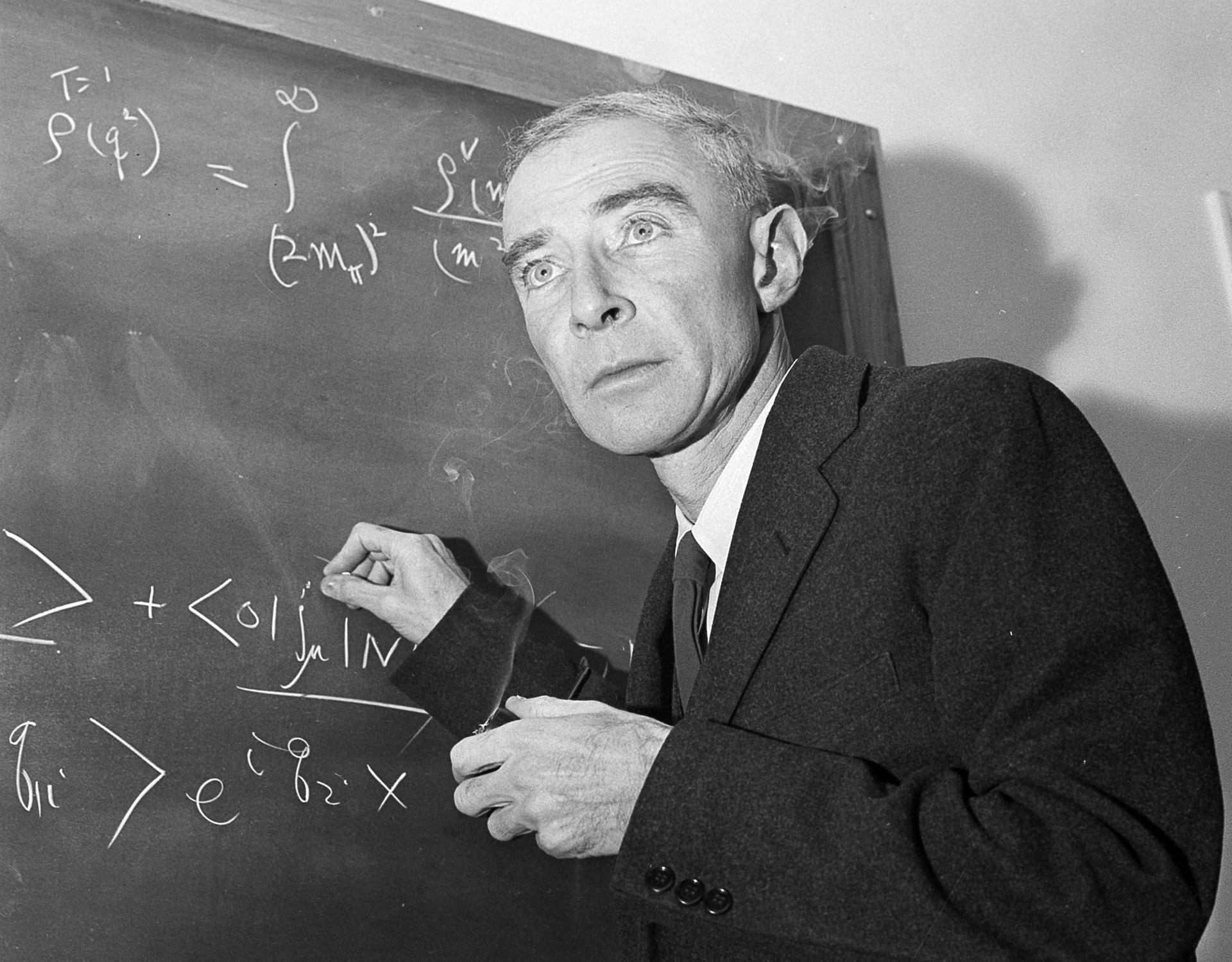

“Oppenheimer,” a film that tells the story of the American physicist who invented the atom bomb, is up for 13 Academy Awards, including best picture and best director.

And it’s expected to win big this weekend.

But one point of controversy in the film is that director Christopher Nolan did not depict any images of the devastating aftermath of the dropping of atomic bombs, which ended World War II.

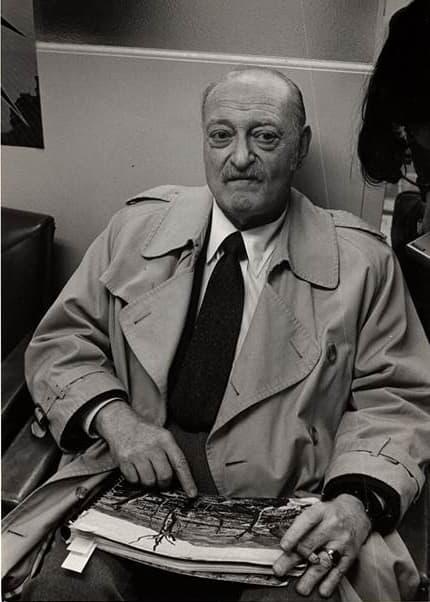

Getting those images out to the public was a longtime quest for Herbert Sussan, a filmmaker who filmed in Japan several months after the bombs were dropped. He was a 24-year-old Air Force officer from New York who witnessed the devastation.

“It’s almost impossible to verbally explain the feeling of walking through miles and miles of just the shattered tops of what had been little homes with nobody — nobody — in the area.”

“It’s almost impossible to verbally explain the feeling of walking through miles and miles of just the shattered tops of what had been little homes with nobody — nobody — in the area,” Sussan recalled in an oral history recorded at Columbia University.

More than 100,000 people, mostly civilians, died in the only use of nuclear weapons during war. The atomic attacks pushed the Japanese to surrender unconditionally and were thought to have avoided the loss of thousands of American lives in an invasion.

Sussan directed an American military film crew that shot 15 hours of color footage with no sound. It is believed to be the only color footage of the aftermath of the atomic attacks. The film shows the wreckage of a large cathedral, shadows burned into concrete and victims being treated for burns.

One of the victims had all the skin on his back burned off and lay on his stomach with bandages soaked in penicillin applied to his back.

The black and white footage of the decimated cities shot by Japanese film crews was confiscated by American military authorities. After the war, Sussan hoped to use the footage his crew shot in a film that would warn humanity of the horror of nuclear war. But the film was designated top secret for more than 30 years.

“There was a concerted effort from the moment we returned with the film to see that the American people and people throughout the world never saw this footage.”

“There was a concerted effort from the moment we returned with the film to see that the American people and people throughout the world never saw this footage,” Sussan said in a 1983 interview. By then, he had retired from a successful career as a TV producer and was terminally ill with a cancer he believed was caused by his exposure to radiation in Japan.

‘A missed opportunity’

Critics of “Oppenheimer” have taken issue with the fact that the film ignores the suffering of Japanese people in the aftermath of the atomic bombs.

“[The ‘Oppenheimer’ film] is such a missed opportunity for a Hollywood film that’s being seen by so many people,” said Naoko Wake, a history professor at Michigan State University who wrote a book about Asian Americans who were in Japan during the atomic attacks and survived. Wake grew up in Japan and went to see the Oppenheimer film because she felt it was her responsibility as a historian.

“Hollywood films are a great venue for not just entertaining but also inspiring and educating people who may not be familiar with the actual consequences of the bomb. Unfortunately, we are again facing this increased fear of nuclear war.”

Greg Mitchell, an author and documentary director, has watched all of the footage shot by American and Japanese film crews. He’s written a Substack newsletter about the “Oppenheimer” film since it opened last summer.

Mitchell is critical of the movie’s one moment in which a victim appears — a scene in which Oppenheimer is hallucinating. The scene takes place in Los Alamos, New Mexico, where the atomic bomb was created. A celebration was held after the news of the bomb’s effectiveness was announced.

“The only victim of the bombing that you see is one young woman and her face kind of melts a little,” Mitchell said. “That’s actually [director] Christopher Nolan’s daughter. And she’s not even Asian.”

Nolan has said that he didn’t include footage of the victims in Hiroshima or Nagasaki because he wanted to tell the story through Oppenheimer’s eyes.

Footage shot by Herbert Sussan’s film crew was declassified sometime in the late 1970s, and some filmmakers got to use it. Shortly thereafter, a dramatic miniseries about Robert Oppenheimer, co-produced by the BBC and GBH, did use actual footage of the devastation in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In one scene, Oppenheimer looks at a film showing a destroyed Mitsubishi factory, a school and a prison 300 yards from the blast. During the scene, one of Oppenheimer’s colleagues asks whether the 140 prisoners survived.

“No,” another colleague replies. “They died in their cells.”

The power of film

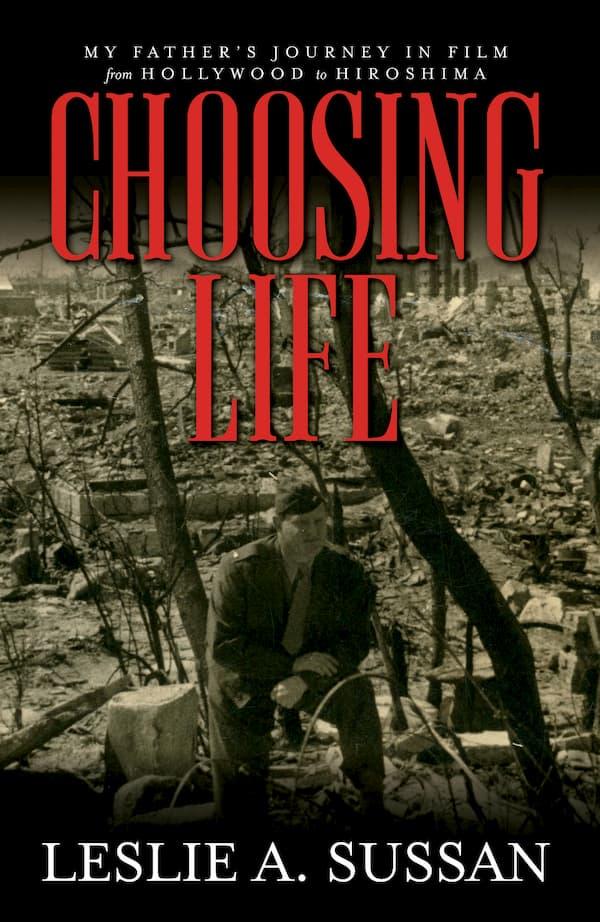

Leslie Sussan wrote a memoir about her father and how the experience he had in Hiroshima and Nagasaki had a profound effect on him.

She went to live in Hiroshima after her father died. While she was there, she connected with some of the survivors her father had filmed.

“He really believed in film and images… and he thought that the only way you would stop the world from using nuclear weapons on people again was if you showed them color footage. Then they couldn’t help but feel what he felt, that this couldn’t be allowed again.”

Mitchell shares Leslie Sussan’s disappointment in the “Oppenheimer” film and her view that the motion picture squandered its chance to deliver a more critical take on the atomic attacks.

“‘Oppenheimer’ was maybe the last chance to reach a very large audience with a more honest appraisal of the use of the bomb and what actually happened,” Mitchell said.

“In that sense, the film is a failure and it doesn’t really matter how many awards it wins or how popular it was.”

It’s set to open at the end of the month in Japan, which is often the last foreign destination for Hollywood blockbusters.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?