On a recent Friday afternoon at Kaufman’s Bagel and Delicatessen, in Skokie, Illinois, people lined up and waited patiently at the no-nonsense deli counter to place their orders.

A toasted sesame bagel with slices of salty lox and chive cream cheese with a tomato slice. A thinly sliced corned beef on rye with extra yellow mustard. A pound of tuna salad. A few warm potato knishes for the road. This place, with a deli on one side and an abundant bakery on the other, has it all.

Bette Dworkin has been the sole owner of Kaufman’s for 30 years. She took over the business from her parents, who bought the deli in 1984. She said her biggest competition is people’s memories.

“It’s what their mother used to make. It’s what their grandmother used to make. It’s what they remember from holiday meals,” she said, sitting by the window on a break between the many catering orders to fill.

People have been coming to Kaufman’s for over 60 years for these classics. It’s one of few in the area that have stood the test of time.

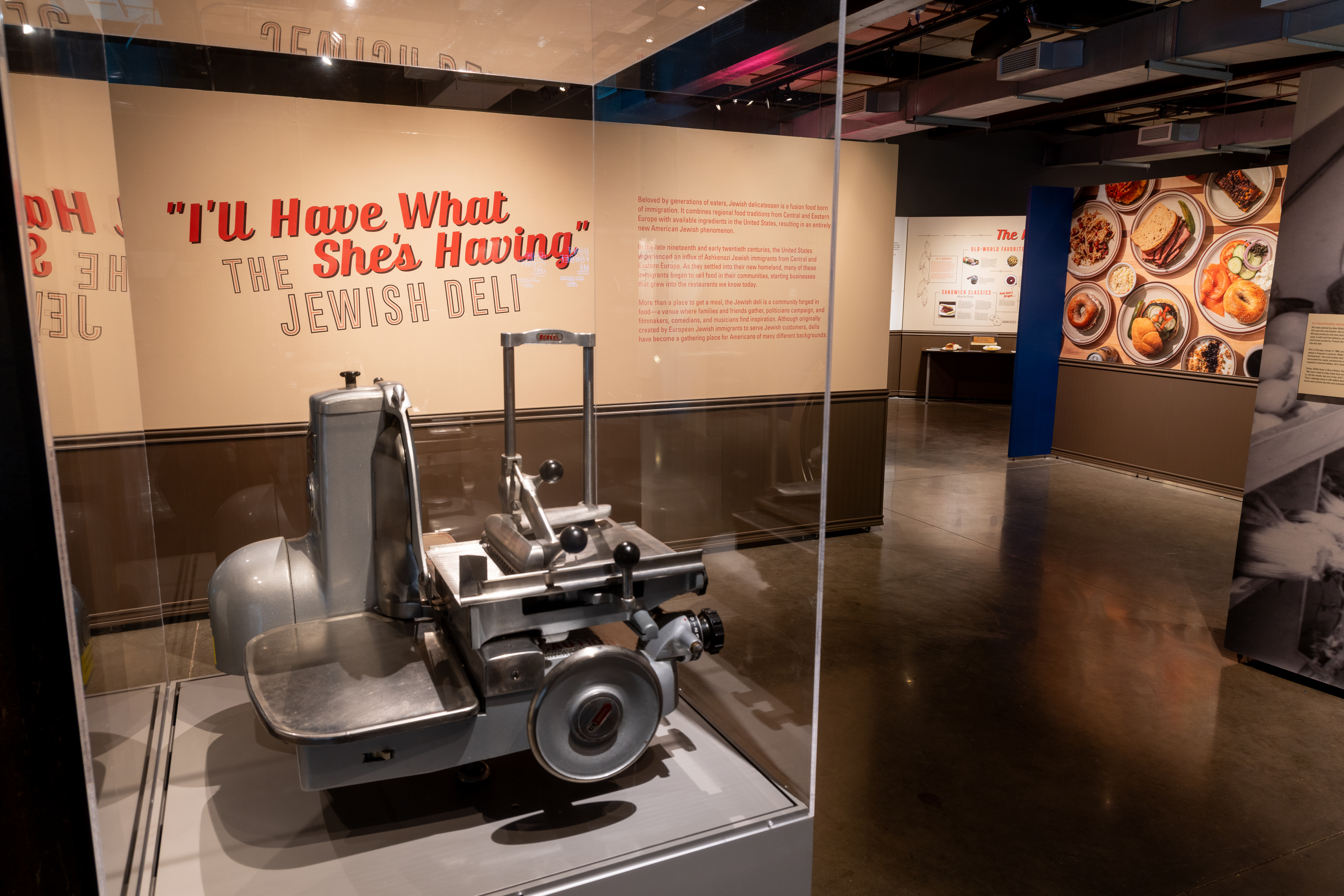

Now, Kaufman’s and other delis like it are being paid tribute at the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center, in an exhibit called, “I’ll Have What She’s Having.” The name riffs off of that famous deli scene in the 1989 movie, “When Harry Met Sally.”

The multimedia exhibit celebrates the evolution of the American Jewish deli “as a community forged in food.” It’s all part of an exploration of how Jewish immigrants and refugees — mostly from Central and Eastern Europe — adapted their traditions from back home to create a uniquely American phenomenon.

“Why is a show about delis at a Holocaust museum? Because of the survivors that were involved in the businesses, that frequented the businesses, that worked at the businesses. So, that was something that we really needed to bring to the forefront,” said Arielle Weininger, the chief curator of collections and exhibitions at the museum.

“In times of sadness and in times of grief, what do you have? You have a deli tray delivered to the shiva house,” she said. “In times of simcha, a bar mitzvah or a family holiday, you have a deli tray sent to the house. So, it’s comfort food for both joy and sadness.”

Weininger said the original exhibition took place at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles, and planning for its debut in Illinois took several years. She said she wanted to give the exhibition a Midwestern spin, highlighting all of the beloved Jewish delis — past and present — in the Chicagoland area.

Kaufman’s original deli meat slicer — fondly nicknamed “baby Bertha” — features prominently behind a glass display case that visitors see when they first walk into the show. That’s because “big Bertha” is still employed at the deli, Weininger said.

The original owner of Kaufman’s, Maury Kaufman, was a Holocaust survivor who migrated to Skokie from Eastern Europe in the late 1940s, along with thousands of other Jewish people. Skokie once had the largest number of Holocaust survivors outside of Israel. It was a big reason why, in 1977, neo-Nazis tried to hold a rally there.

When Dworkin’s parents first bought Kaufman’s in 1984, she said that nearly all of Kaufman’s employees were Holocaust survivors. “I’d say a minimum of 80% of the workforce, if not more, had numbers on their arms,” Dworkin told The World.

Places like Kaufman’s became an essential part of postwar life in America for European Jewish refugees who settled here.

On a recent Friday morning, groups of chatty students mingled among older visitors taking in all the sounds and sights of Jewish deli life in America – including original neon deli signs like the one from Nate’s Deli, made famous in the 1980s film, “The Blues Brothers,” where Aretha Franklin famously bursted out into song.

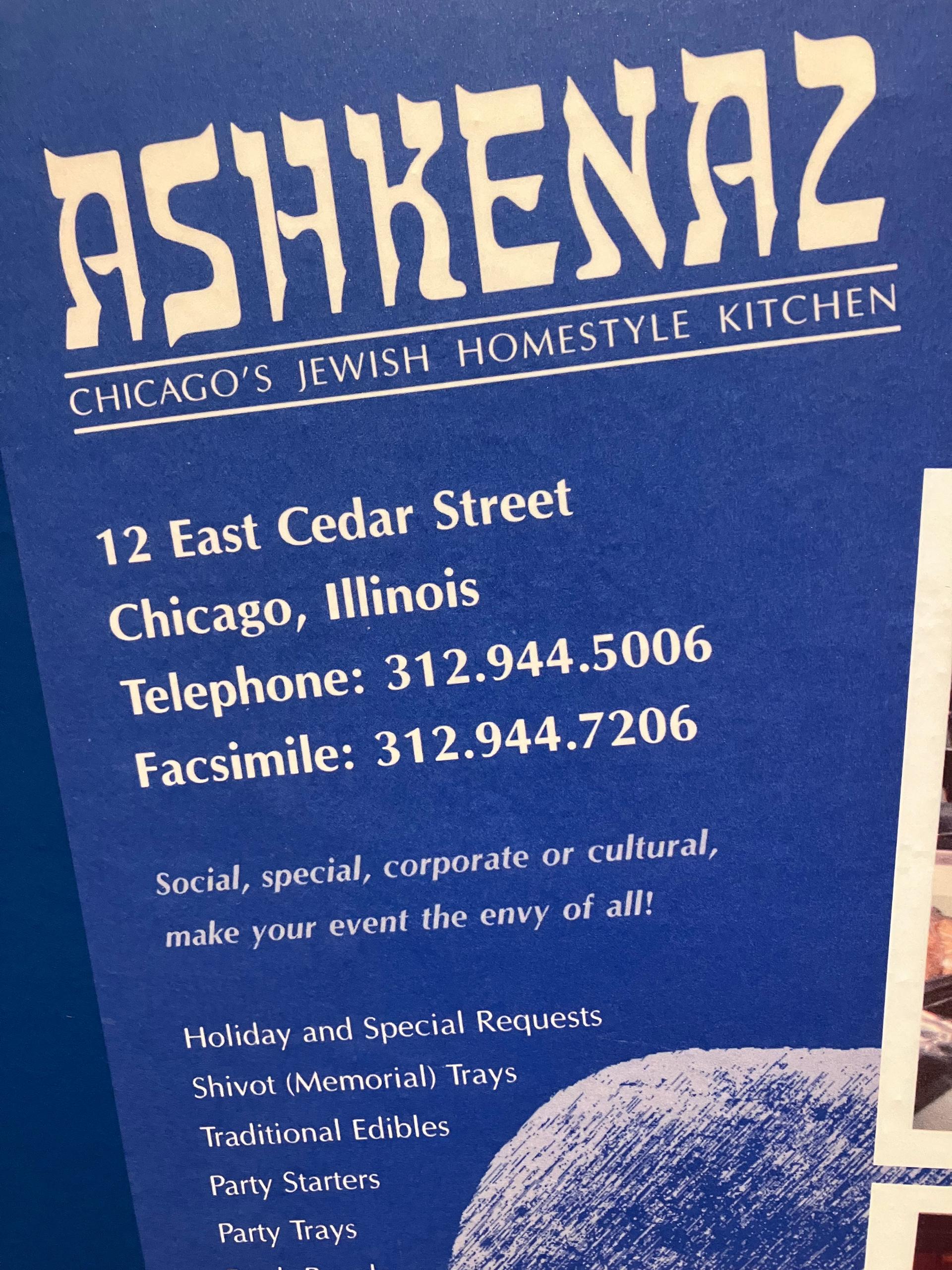

Jan Mosoff was among the many enthusiastic visitors at the exhibit. She said she remembers going to Ashekenaz, her favorite deli on Chicago’s north side — but only once a month.

“We didn’t have money,” she said. “But once a month, we would definitely go out for Jewish food and we’d go to Ashkenaz. it was, like, the biggest treat you could have.”

The exhibit includes old deli menus, matchbooks and memorabilia from many of these places, along with a wall of black-and-white photos featuring many of the original deli owners in action behind the counter.

There’s also a list of so-called Yiddishisms — words like balabusta (“a good homemaker”) and bisel (“just a little bit.”)

Yiddish was once the most widespread language in 19th-century Jewish European communities. The language nearly went extinct when many of its speakers were killed in the Holocaust.

“I think it’s very significant that those Yiddishisms are up on that wall,” Weininger said.

“Yiddish is a language that is now pretty much, outside of the Orthodox Jewish community, gone. And yet, most of our relatives would have spoken it.”

Jan Mosoff said the show is a good reminder that there are many different parts to being Jewish.

“It’s not just a religion, it’s a culture,” she said. “And people grew up in different areas and have different experiences.”

Jennifer Rosner, from Highland Park, agreed. She said she feels more culturally Jewish than religious, and that food is the centerpiece of any good culture.

Many of the old delis have long sinced shuttered, partly due to the owners dying or moving away, and changing food trends.

But Rosner is part of a new generation of deli lovers and said she even hopes to open up her own bagel shop one day.

“I just feel closer to my heritage when I’m in a delicatessen,” she said.