“Was there a sign? Did we miss the sign?”

Vitalii Kolesnichenko was standing on a dirt road between two rusting warehouses with a big smile on his face.

“You made it,” he said.

Kolesnichenko is the CEO and founder of a Ukrainian drone company called Airlogix. And he agreed to give the “Click here” podcast a tour of his drone factory on one condition: That we keep its location a secret.

The process of arriving was so stealthy, the night before our arrival, he sent us GPS coordinates — a little, red pin dropped in the middle of nowhere — instead of an address. It turns out the facility is so well-hidden that three journalists tracking it on an iPhone managed to drive past it three times.

“You want us to have a sign?” Kolesnichenko said, extending a hand. “What should it say? Airlogix is here, we’re making combat drones for the Ukraine military, so Russia this is where to launch your missiles?” And then he burst out laughing.

He isn’t being dramatic. Pop-up drone factories like his are working around the clock to build as many drones as possible and ship them to the front-line fighters who need them. The government in Kyiv has earmarked some $1 billion to support drone startups like his, and Russian forces are trying to find them to put them out of commission.

The battle between Russia and Ukraine has been asymmetric from the start. Ukraine has responded to Russia tanks and artillery with scrappy alternatives, and none have emerged more important than the tiny flying machines that have allowed Ukraine to punch way above its weight on the battlefield.

Initially, Ukrainian soldiers tinkered with hobbyist racing drones, adding explosives and then dropping the payload on Russian positions or weaponry. It became clear right away that drones worth hundreds of dollars could be used to effectively destroy Russian tanks and artillery batteries worth millions.

Ukraine began importing as many drones as they could. They even set up a fund that would allow them to buy and import all kinds of drones to create what came to be known as “The Army of Drones.”

Most of the MacGyvered drones Ukraine had been deploying came from China, from companies like DJI, Autel and RushFPV. DJI controls about 90% of the global drone market. Then in July, China announced that it would begin restricting drone exports out of concern that they were playing too great a role on the battlefield. China has said it doesn’t want to take sides in the field. (Russia uses much more expensive drones from Iran and Turkey.)

The Chinese export restrictions went into effect Sept. 1. In anticipation of that ban, hundreds of entrepreneurs like Kolesnichenko have stepped in to create an entire drone industry from scratch.

“There was nothing here before the invasion,” Kolesnichenko said from the shop floor where more than a dozen workers were bent over fiberglass fuselages and wooden airframes bound for the front. “Two years ago, we were a little start up making cargo drones. There were, like, 10 people.”

Now, he employs 60.

‘We wish you best luck’

Kolesnichenko is a nuclear engineer by training and a pilot by inclination. He’s built like a linebacker and laughs easily.

“Planes were always my dream, my child dream,” he said. “We thought drones were the future, and we were going to use drones to deliver things to hard-to-reach places because no one was really doing that yet.”

So, he quit his engineering job and began dedicating himself to building Airlogix.

He and his team worked up some designs and built a few prototypes and then, in 2021, took them to a trade show in Las Vegas where investors seemed immediately interested.

“There was an executive from some hospital chain, and he wanted to buy these drones to deliver blood samples,” Kolesnichenko said. “Then, there was a businessman from the Caribbean and he wanted to use them to deliver groceries, alcohol and cigars between the islands.”

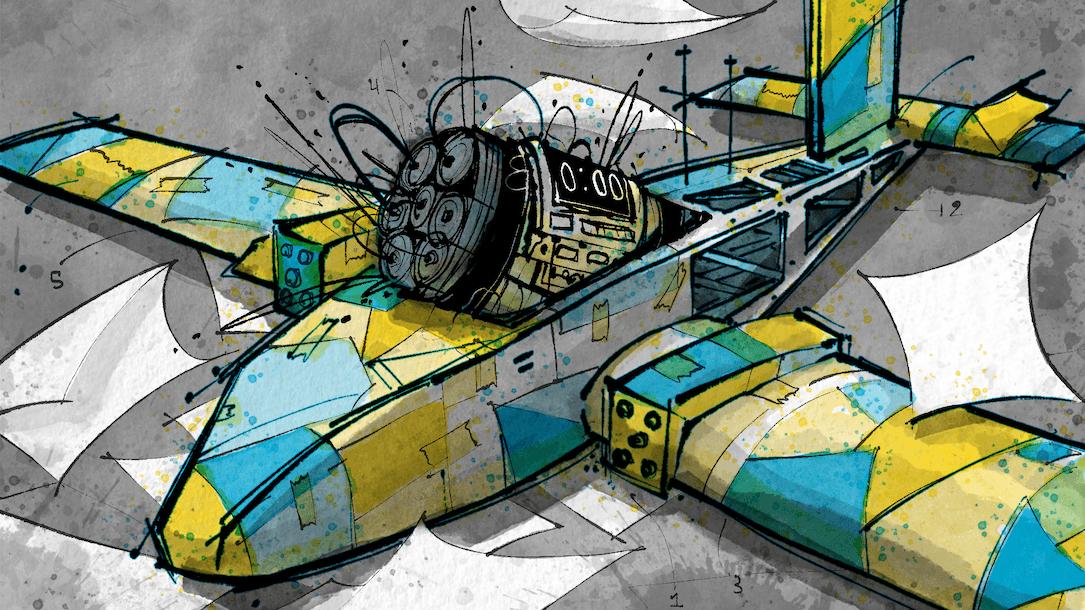

Airlogix’s first drones looked like little Learjets. They were painted white, with tilt rotors and a logo on the tail.

“The 24th of February invasion completely changed our plans,” he said. The investors — “[they] vanished,” Kolesnichenko said. “They said, [we] wish you [the] best [of] luck. We hope you will win, but I’m sorry we’re out.”

In the war’s first weeks, Ukraine didn’t allow any men between the ages of 18 and 60 to leave the country, and many were conscripted into the military. The Territorial Defence Force, which is now a branch of the regular army, originally brought together military reservists and local volunteers. They were given a month’s training and then dispatched to the front.

What that has meant as a practical matter is that just about everyone in Ukraine has a family member or a friend fighting the Russians and, because people are staying in touch with their friends and family at the front, it has opened up direct lines of communication never seen before in a conflict.

People back at home are getting real-time information from fighters at the front and that has meant that care packages don’t just include food and favorite cookies; they also provide things like ammunition and, more recently, drones.

“We talked to militarists who were in our inner circle to ask them what they needed and then we started to make them,” Kolesnichenko said. “I joke that our drones are like a Rolls Royce, each one is actually made by hand. We don’t have an automated line because that demands a lot of resources and investment” and time — none of which Ukraine has to spare.

Artisanal drone factories

The Ukrainian military’s burn rate on drones is thought to be thousands per month. According to one report by the British think tank RUSI, some 10,000 drones are shot down or rendered unusable every 30 days. (RUSI based the estimate on what it said were extensive interviews with Ukrainian military personnel.) It’s impossible, at this point, to know if the number is accurate. What isn’t in dispute is that the appetite for drones is voracious.

Drones are now human-guided missiles, reconnaissance vehicles and even kamikaze weapons. Ukrainian officials will tell you they save lives by virtue of the fact soldiers can fly them from the relative safety of a foxhole or a trench. Russians had been triangulating drone signals to figure out where operators were hiding, but Ukraine now has so many different kinds of drones making their way to the fight, using so many different frequencies, that Russians are having a hard time finding them. It was an unexpected benefit from Kyiv’s decision to let a hundred drone factories bloom.

We visited several, and Kolesnichenko’s pop-up workshop is typical. It looks like something a hobbyist would build in a garage: Long workbenches are covered in butcher-block paper and drones in various stages of development. There are sanders and files and glue, and if you narrow your eyes, it looks like an underground facility you’d imagine out of World War II — like something the French resistance would run.

“We make molds here,” Kolesnichenko said, patting half an airplane on a rollaway table. “We make airframes, the fuselage, the wings, the tail everything.”

Around us, dozens of workers, mostly men, are bent over balsa wood endoskeletons of aircraft. A dozen wingless fuselages are parked in neat rows on metal shelves. Against the wall, fiberglass sheets hang in rolls like wrapping paper. There is a constant hum from sanders and the sweet and sour tang of adhesive, melting fiberglass and sweat.

Kolesnichenko said that the UAVs he’s building now look nothing like the cargo drones he intended to build more than a year ago — “totally different,” he said.

The commercial drones were designed to take off in the open and be tracked by air traffic control. Combat drones need to be sturdier to withstand the harsh conditions at the front, survive launches from secret positions and carry electronics that jam Russian air defense systems.

“We start from molds. The surveillance drones or kamikaze drones are built one half at a time,” he said. “We’re using resin and fiberglass and then bake it in an oven.”

The oven looks like a repurposed shipping container. They’ve cut a hole in the back, inserted a tube and connected it to a heater. The drone fuselages bake in vacuum-sealed bags for about eight hours. Think sous vide cooking without the water.

And, because of the Chinese ban on exporting drone parts, Kolesnichenko has started sourcing his electronics from Europe. He had just received a delivery when we arrived.

“It’s from England,” he said, ripping open the package. “There’s the power cable, a transmitter, we use it to communicate with laptops in the field. This is great stuff.”

This artisanal drone shop turns out about 12-15 aircraft a month, which may not sound like it will make much of a dent in Ukraine’s need for thousands of UAVs every month, until you realize that there are hundreds of factories like this across the country, all trying to build budget drones in a multibillion-dollar war.

A new military tech industry

A few days later, we meet Alex Bornyakov, Ukraine’s deputy minister of digital transformation in charge of IT industrial development, at a kind of massive WeWork-style space in Kyiv. A Columbia University graduate, he is wearing a quarter-zip sweater and jeans. The place is humming. There are three floors of young people on laptops sitting at communal tables drinking lattes. The place looks very SoHo, with giant, oversized warehouse windows and soft jazz playing in the background.

One of Bornyakov’s many jobs is to try to systematize the grassroots effort to send military equipment to the front.

“We’ve had people saying directly to people [who are fighting], I’ve got 50 drones, 20 drones, and people in the fighting would say ‘Oh, those drones are, those are good’ and start to use them,” he said. “We know people are reaching out directly to officers with offers of drones and they’d be deployed, but the general staff would know nothing about them. The process was chaos.”

Bornyakov had to find a way to organize the effort without snuffing it out.

Before the Russian invasion, there was almost no private defense industry in Ukraine, Bornyakov said.

“Most of the regulations governing military tech are from the 1960s or ’70s,” he said.

The Army of Drones program did a lot to ease the procedures and make them faster and more transparent. When people started to see that, they started to create companies and offer their products and try to get them certified.”

So, they have developed a two-track system: One is informal, like the way Airlogix works through friends and family contacts. The other will be more formal and systematic, closer to traditional military production.

Before the war, the government seemed to actively discourage public-private partnerships by, among other things, instituting a ceiling on the profits any company could make on a military contract. Bornyakov said companies were only allowed to make 1%. Now, the ceiling is 25%.

“This resulted in hundreds of drone companies springing up,” he said. “And now, they’re starting to compete with each other with technologies with new solutions.”

Then in April, the Ministry for Digital Transformation launched a program called Brave1, an effort to push innovations to the front lines faster. In Bornyakov’s telling, the process is still pretty simple. Potential suppliers sign into the Brave1 portal, provide some sort of identification to prove they are Ukrainian, and then offer ideas and innovations that can help win the war.

“So, let’s say you’re a small company, you’re doing something in a garage and you have this prototype that works,” he said. “We can help you test this with the military and if they like it, we can start procurement, you can have your first contract, you get your money, you reinvest it, you get bigger contracts. ”

Consider what happened with a Ukrainian company called Temerland. It had an idea for a machine gun turret on wheels, almost like a little tank.

It is controlled remotely through a tablet, which means Ukrainian soldiers can shoot Russians from the relative safety of a foxhole. The idea was certified by the military in two months, Bornyakov said, and is already in use on the battlefield. And he said there is much more where that came from.

“At this point we have more than 650 applications in Brave1,” he said. “So, this actually shows that the defense tech industry is booming in Ukraine. It is hard to imagine that a year ago that didn’t exist at all.”

If there has been a recurring theme in this high-tech war, it has been Ukraine’s ability to innovate by necessity. It has surprised just about everyone by being craftier and more nimble than its Russian enemies and using that to great advantage.

“We fight with the enemy much, much bigger than us in terms of their access to everything — hardware, people,” he said. “If we just give them a symmetric answer, we’re not gonna win this war. We need to find asymmetric solutions. So, it’s basically like fighting warships with marine drones. That’s the kind of solution we’re looking for.”

Which may be why Kolesnichenko has his designers over at Airlogix working on a new drone design. They’ve envisioned an aircraft that arrives on the front lines, partially assembled, in a tidy little package. A drone in a box, if you will.

Nazar, 21, is a student and design engineer at Airlogix, and he’s spearheading the project. He asked us only to use his first name to protect his identity.

“It’s still testing and we are trying to select the most simple tool in assembly,” he said. “The concept is, like, it can be assembled, you don’t need special education to assemble it, you just clip it together like Lego.”

You just need two people and some glue, he said. It would take two days to build. They are rushing production to get it out into the field. “Maybe it’ll be ready in a month, maybe more, maybe less,” he said. “But not a year. We don’t have a year.”

An earlier version of this story appeared on the “Click Here” podcast from Recorded Future News. Additional reporting by Daryna Antoniuk.