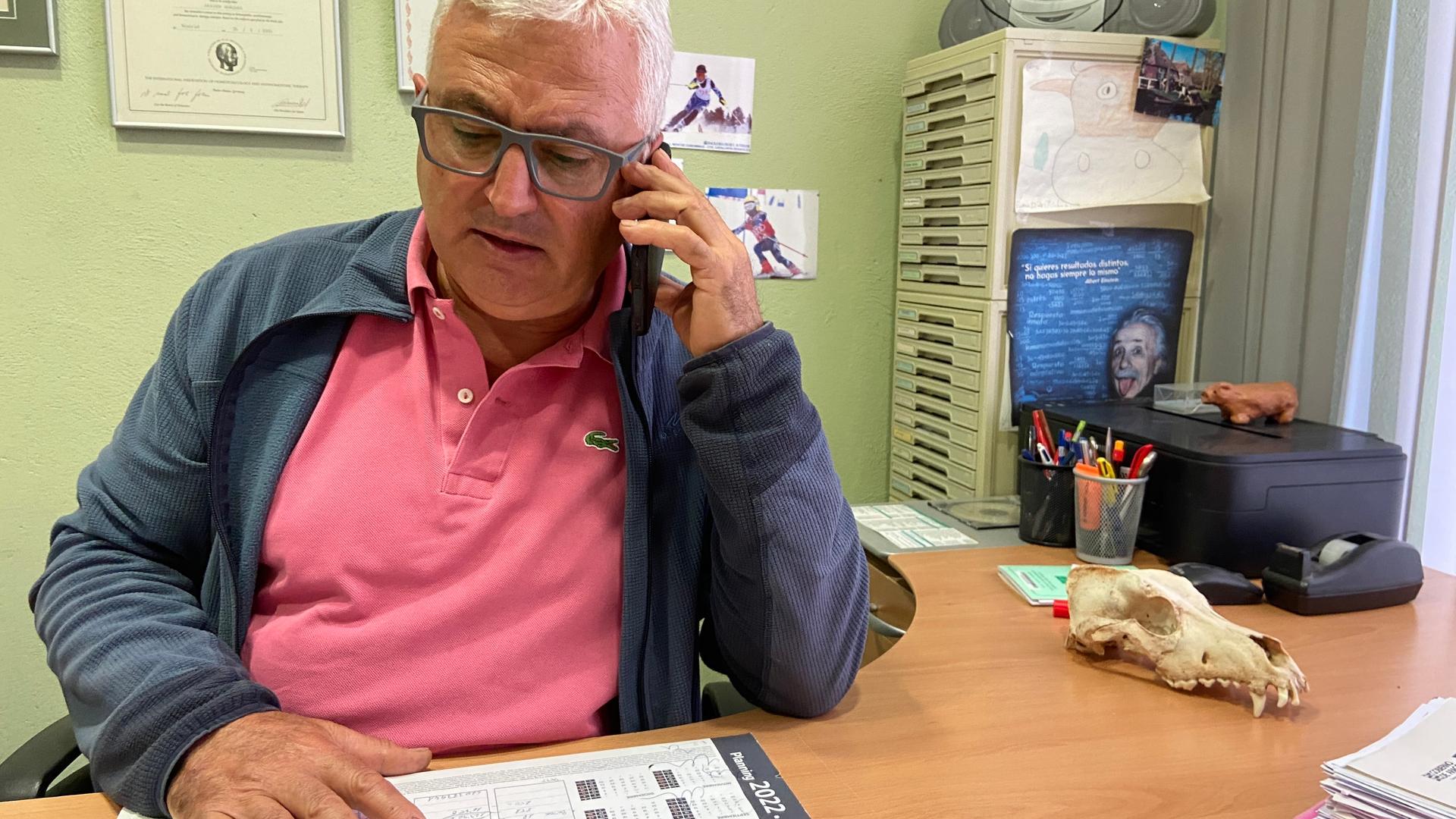

Veterinarian Javier Bordas is very busy.

On a recent morning, he rushed back into his small-town clinic in the village of Pont de Suert in Spain. He had just been at a cattle ranch near the French border, where he said he saw yet another case of Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease, or EHD.

Dr. Bordas told The World that there were multiple outbreaks in the 10 days since the virus reached the region.

“I saw three sick cows,” he said. “And I’ve just taken a blood sample from another. Ranchers have even called me from France, but I tell them I can’t go.”

The mosquito-borne virus first jumped from North Africa to Italy last year. Soon after, it appeared in southern Spain. It’s now crossed the Pyrenees during the warmest fall ever recorded in Europe.

“We’re waiting for the cold to arrive,” Bordas said. “Normally, at this time of year, it should get down to just about freezing at night. If the weather were normal, I think this mosquito would disappear.”

On the day Bordas spoke to The World, it was about 70 degrees. The week prior, temperatures were in the high 80s. People wore t-shirts and shorts instead of the down parkas normally seen in late October.

Bordas’ phone rang — a local rancher, Josep Feree, said he was bringing a sick cow down from the pastures to his barn just down the road.

Bordas sped off in his white work truck and reached the barn before Ferre.When the rancher showed up — the sick cow was nowhere to be seen.

“We couldn’t move her,” he said, exasperated. “She kept charging [at] us [when we tried]. She’s been sick for a week now.”

That means a week with little or no food and water — because one of EHD’s main symptoms is excruciatingly painful sores on the tongue and mouth.

Four of Ferre’s 300 heads had caught EHD. Bordas checked on another one that had gone days without food. She was alone in a corner pen and could barely stand up.

Ferre held the cow’s mouth open, as Bordas shined a light inside.

“You can still see some ulcers there,” he said. “But she’s getting better. Look under her tongue. She had a sore that ran from one side of her mouth to the other.”

Ferre pushed some hay her way, and the cow tentatively began to chew.

There was a sense of relief. But it didn’t last long.

The big picture is that there’s no cure for EHD beyond painkillers and prayers.

“These days, this is all we ranchers are talking about,” Ferre told The World. “Here, luckily, so far, none of my cows have died.”

The mortality rate is low. But hundreds of cows in Spain have, in fact, died. Many more have had miscarriages. Infected bulls have gone sterile.

The one preventative weapon ranchers have is old-fashioned bug spray.

“The repellent we use works on ticks, so hopefully, it’ll keep the mosquitos away too,” Ferre said.

But if the disease’s rapid spread northward is any indication, repellent won’t cut it.

“I think the mosquito got here so fast inside trucks,” Bordas said. “Because the first cases appeared on ranches right along the motorway. We get like 2,000 trucks a day passing through.”

Initially, health authorities said mosquitoes wouldn’t survive much at 3,000 feet above sea level. But with the summer-like conditions, Ferre said one of his cows got infected at twice that altitude.

But can’t they take the animals up even higher until winter arrives?

“No, no. Quite the opposite,” Ferre said. “We need to bring the cows down now. Because they’ve grazed all the pastures clean. There’s no food up there.”

Ferre’s cows must descend or face starvation — even if coming down means possibly getting EHD.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?