On a recent evening, a small crowd of locals in Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan, gathered in the offices of Esimde, a research organization that focuses on modern history, to take in a documentary and lecture about a bloody uprising in the country that occurred in August 1916.

That summer, Russian authorities forces in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, which were then part of the Russian Empire, announced a draft to enlist Central Asians to support Russia in World War I. The Russians killed thousands who resisted, and scholars estimate that at least 100,000 more people died trying to flee to nearby China, although some estimates put the total number of dead at more than triple that.

Most of the victims died while crossing over the snowy mountains that separate Kyrgyzstan from China. The tragedy became known by the Kyrgyz word urkun, which is often translated as “exodus,” but one Kyrgyz scholar said it means something closer to panicked animals running away from danger.

More than a century later, historians and locals say it is still complicated to talk about the episode, in part because of pressure from Russia to downplay Russia’s role in the tragedy. But every summer, groups like Esimde strive to commemorate the tragedy.

“Our government can’t openly recognize the Urkun, but ordinary people and independent organizations like ours really want people to know about what happened,” said Gulzat Alagoz Kyzy, a researcher with Esimde who helped organize the documentary screening.

Although the Urkun occurred several generations ago, the memories of what people endured have been passed down through generations surviving as an oral history.

“My family fled up toward the mountains, stopping during the day to hide in bushes,” said Anvar Nanshanlo, an ethnic Dungan man from the regional city of Karakol.

Nanshanlo’s grandmother was just 8 years old during the uprising. After Russians entered her village and started burning down houses, she and her family fled to the nearby mountains that separate Kyrgyzstan from China.

But the journey over the mountains was no easy feat. Even in summer, snow cover and frozen glaciers remain in the mountains of Kyrgyzstan.

“People would cut out steps in the ice with knives and axes, put one foot forward and then start cutting the next step,” Nanshanlo said as he described the slow journey his relatives took through the mountains to China.

Many Kyrgyz didn’t survive the harsh conditions.

Decades later, one man who visited the mountains where it is estimated that hundreds of thousands people fled during the 1916 uprising described finding a river with banks still “covered in human bones.”

Asel Daniyarova, a Kyrgyz historian, and her husband, Vladimir Schwartz, said that they found documents in Russian archives, which they said suggest that Russia intentionally used the uprising to displace the local population through violence to make way for Russian settlers.

Not all historians share this interpretation of the events, but many agree that Russia tried to control the historical narrative about the Urkun starting during the Soviet period.

“In Soviet times, there was almost no information in school textbooks about the Urkun,” Daniyarova said.

But after the Soviet Union fell, Kyrgyzstan became an independent country and Indigenous peoples, not Russians, had a chance to write their version of history.

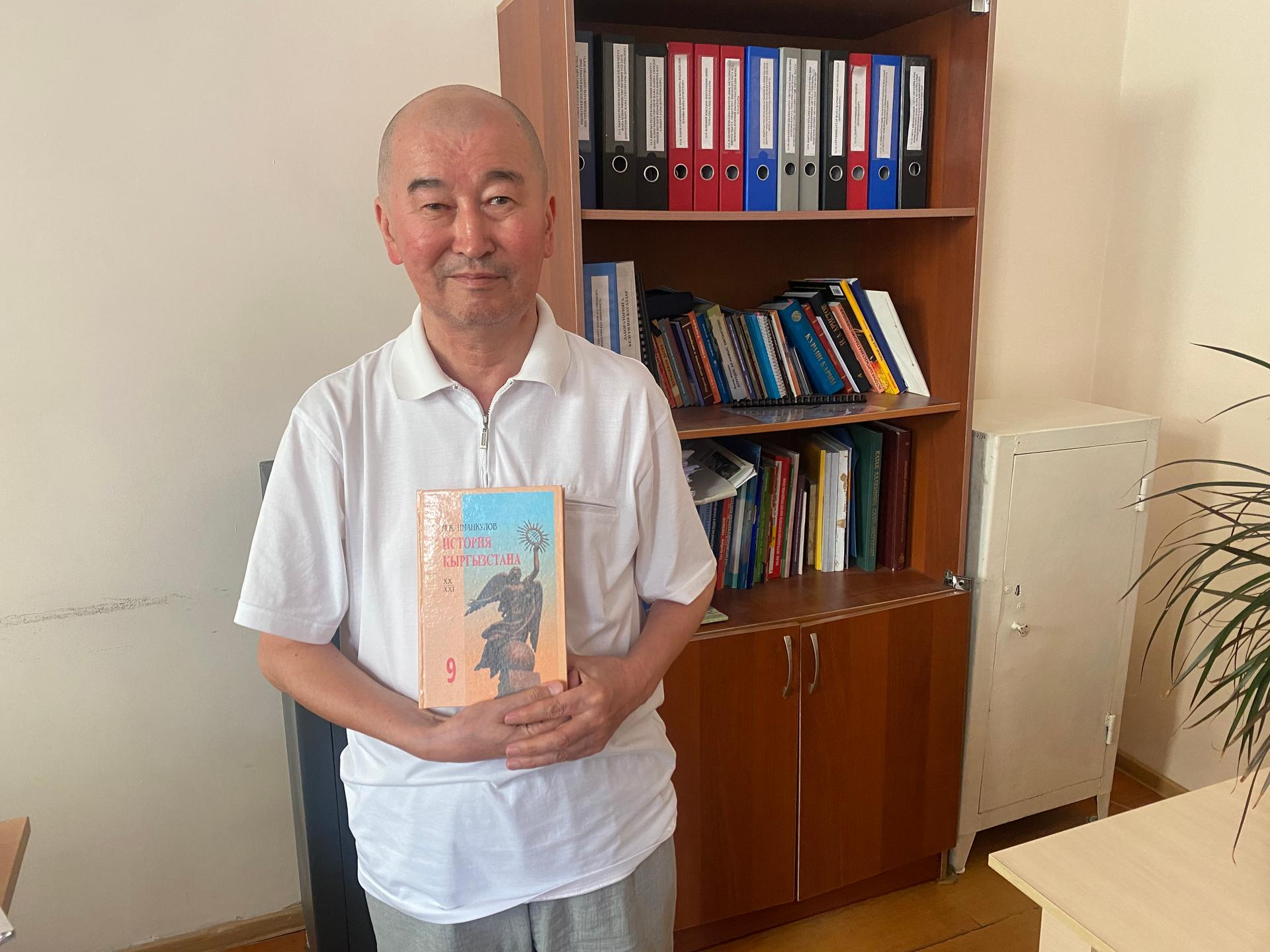

Myratbek Imankulov, head of social studies and humanities at the Kyrgyz Academy of Education, wrote a history book for high school students published in 2006, which includes a detailed section about the Urkun.

After the book came out, some Russian academics accused Imankulov of falsifying history. He was even threatened with legal action for spreading propaganda.

“They wanted to silence me so other historians would stop their work,” Imankulov said.

Despite the pressures against him, Imankulov’s book is still in print. But other Kyrgyz who have chosen to tackle the subject of the Urkun have faced some form of censorship.

A 2016, Hollywood-style movie about the Urkun (also titled “Ukrun”) produced by Kyrgyz filmmakers faced significant delays before gaining government approval to show the film in Kyrgyzstan.

Later, one of the producers told the local press that the authorities asked them to change some parts of the film before its release, presumably so as to not sour relations with Russia.

Imankulov said the scale of carnage carried out by Russia during the Urkun is comparable to the slaughter of civilians last year in the Ukrainian city of Bucha.

“These are crimes against humanity and even though the two events are separated by more than 100 years, they are essentially the same,” Imankulov said.

But acknowledging Russia’s responsibility for crimes committed recently in Ukraine, or last century, is difficult in countries that maintain close ties with Russia. Central Asian countries still greatly depend on Russia economically and their leaders have refrained from outwardly condemning Russia’s actions in Ukraine.

Still, some Kyrgyz are determined to make sure that Russia’s influence in their countries as a colonial power is not forgotten.

“Up until now, there is a wound, and we have to bring the truth, otherwise it will never be healed,” Daniyarova said.