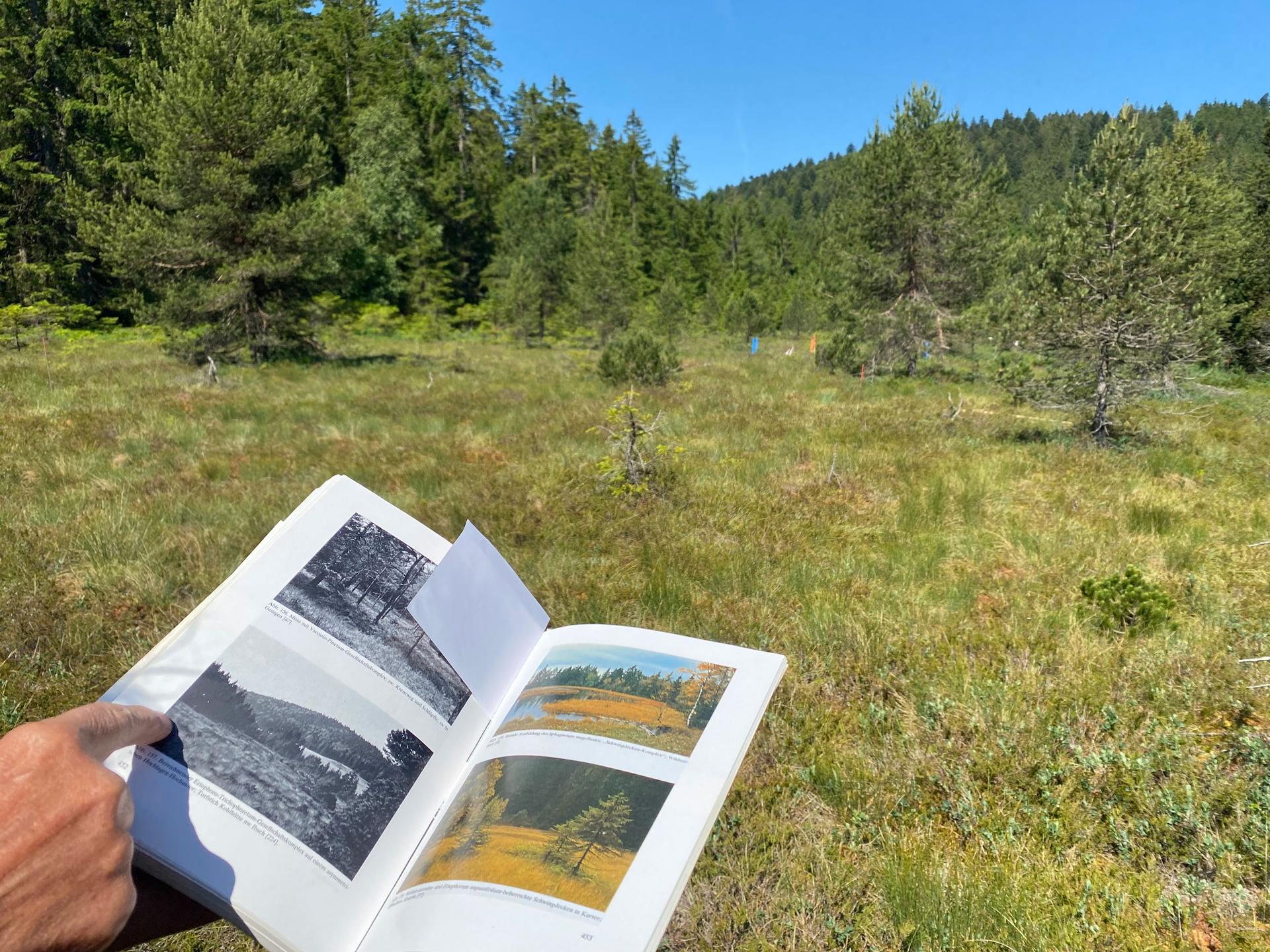

Thomas Sperle held up an old photo of a bog and looked directly at the exact same spot, 50 years later. The photo shows a marshy area, with water winding through the grass. Today, it’s mostly dry.

“In this part of the bog there were no trees,” Sperle said. “And nowadays, a lot of trees.”

The trees represent new growth. But in a bog, a tall tree is not a sign of life.

“The tree is a sign that the water level in the ground of the bogs is sinking,” Sperle said.

Germany’s Black Forest is the backdrop for countless fairytales. But there’s a darker story emerging about a loss of biodiversity that’s hard to see with the naked eye. And it’s not the only place where a pretty picture can mask a trend of extinction.

Across the globe, the extinction of species doesn’t necessarily mean a desolate landscape – so it takes specialized, time-intensive research to find out what plants the planet is losing.

In 2017, Sperle started surveying dozens of bogs in Germany’s Black Forest. For three years he counted plants, some just a few centimeters long. He often spent nights in his camper van. He made lists of plants and their quantities and compared them to a survey from 50 years ago.

“I find out that nowadays much less species are growing,” he said.

Two plant species have gone extinct, and several more will likely disappear in the next 15 years.

“If this trend in the future will go on, we have … the extinction of I think 10 species in all the bogs,” Sperle said.

The plants that are dying out are mostly what are called specialists, which do well in a very specific setting. Meanwhile, generalists, which can thrive almost anywhere, are increasing. Sperle and his research partner, Helge Bruelheide, attribute the homogenization to hot, dry summers from climate change.

“It results in a type of globalization,” Buelheide said. “So you lose the difference between different habitats.”

Bruelheide is a professor of geobotany at Martin Luther University in Halle, Germany. In another study in northern Germany, he found that over two decades, the landscape had gotten greener.

“Most people think, ‘Wow, yeah, it’s a good sign,’” he said. “Because if something gets greener, we have less concrete and more nature.”

But in this case, greener meant a loss of other colors.

“Colorful meadows have disappeared,” he said. “Less colorful flowers mean you have less pollinators.”

At the University of Minnesota, Elizabeth Borer is also researching biodiversity – but through a more experimental lens.

“I want to know what will happen if I change the conditions, often trying to simulate something like what future Earth might look like,” she said.

As humans burn fossil fuels, it’s not just carbon that is released. Nitrogen and other nutrients are going into the air and falling back down in the rain. Borer simulates these higher nutrient levels in a controlled setting to see what happens to plant biodiversity.

“What we see there is a continued loss of species from those areas,” she said.

More nutrients might sound like a good thing.

“If you have a single outcome in mind, which is more plant, you are likely to get more plant,” Borer said.

There’s more vegetation overall in the short term because the generalist plants are thriving. But they’re often crowding out the specialist plants, so biodiversity declines.

“The little seedlings or small-statured plants don’t have the light resources they need,” she said.

What does a loss of biodiversity actually mean for the planet? Fewer plants mean fewer pollinators, which are important for food production. Plants also store carbon and keep it out of the atmosphere. Bogs are especially good at this.

“The bogs are holding carbon dioxide in very great size,” Sperle said.

Back in the Black Forest, Sperle said if nothing is done, these particular bogs could disappear completely by the end of the century. So he’s moving from research to action.

Four years ago, he surveyed a tiny birch tree called a Betula nana and discovered there were only 50 left.

“This is a very small tree,” he said. “It is also a specialist of bogs.”

This variety of birch tree is about the size of a bonsai. It was almost extinct for lack of water. And unlike taller, generalist trees, this tiny one is supposed to live in the bog. So Sperle had an idea.

“We take in water from a little stream opposite the bog,” he said. “The tube brings the water in the bog where this little birch is growing.”

With the extra water, they managed to stabilize the 40 remaining plants.

Betula nana is just one small species, but every loss has untold consequences for the planet.

“We don’t know exactly what role every species or every system of species has,” Sperle said. “And we cannot say, ‘Oh, that’s going away. It is nothing.’”

Sperle said it will take both research and action to find out what kind of extinctions are hiding behind beautiful trees and vibrant green spaces, and keep any more species from disappearing.