An important fishing village in Senegal is on the verge of disappearing as sea levels rise

The city of Saint-Louis, in northern Senegal, is grappling with a dire reality: rising sea levels.

The former administrative capital of French West Africa, Saint-Louis sits between the Senegal River and the Atlantic Ocean. Its highest point stands just 13 feet above sea level, and it gets waves from both fresh and seawater that have become a growing threat.

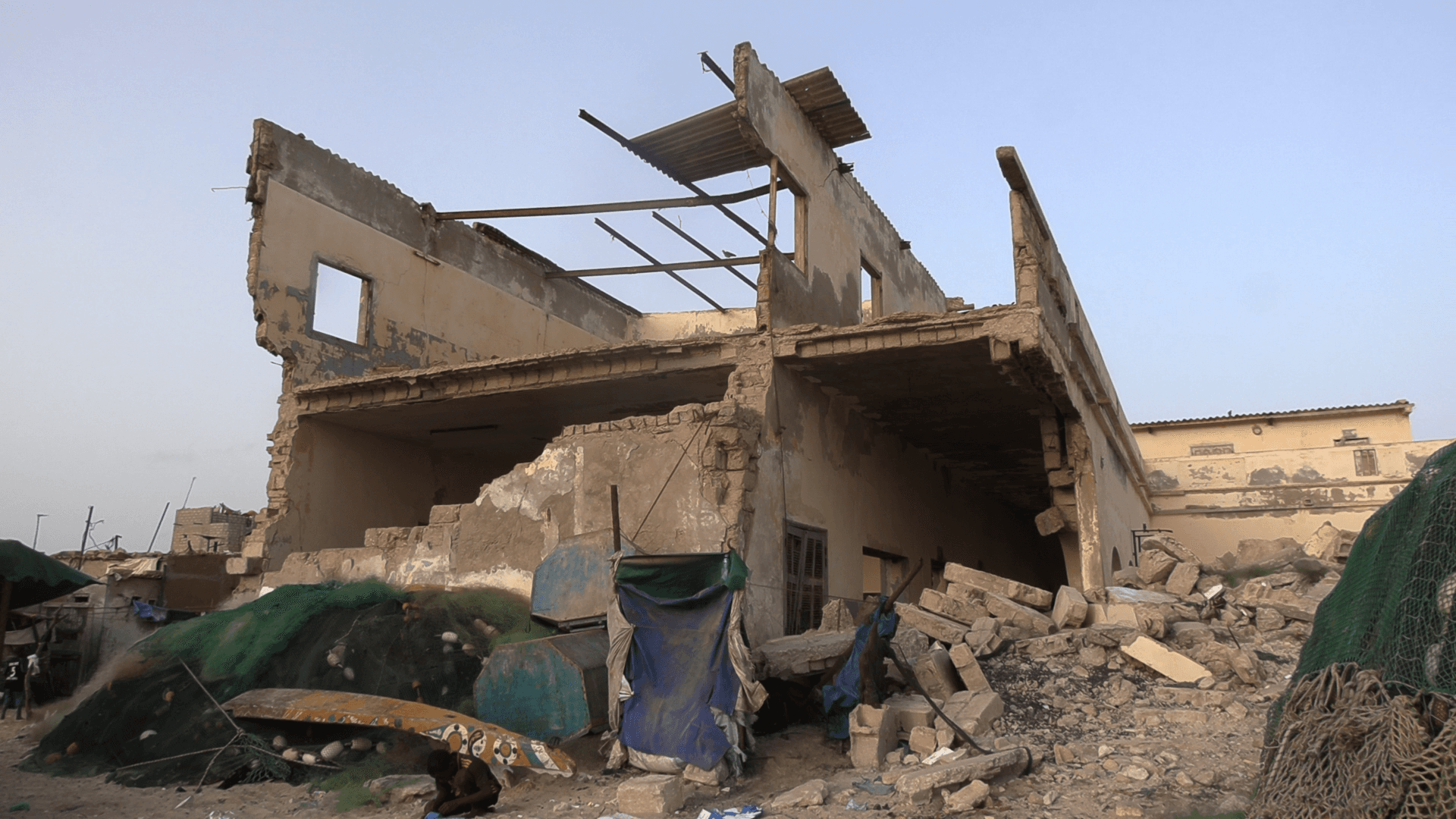

Fishing is one of the main industries in Saint-Louis. But the city’s fishing village of Guet Ndar is now on the verge of disappearing.

“We had to walk very far to reach the ocean, but now we have it right in front of our houses.”

“Growing up, what we used to see is not what we’re seeing today,” said Cheikh Badiane, a retired fisherman who grew up in the neighborhood and still lives there with his children and grandchildren. “We had to walk very far to reach the ocean, but now we have it right in front of our houses.”

Several decades ago, Badiane recalled, the water was half a mile away. Now, it washes up to the houses on the shore, sometimes seeping through the windows.

In 2018, a high-tide event destroyed many houses, mosques and schools in Guet Ndar. About 1,500 people were forced to move to Diougop, a displacement camp funded by the United Nations that’s 5 miles away inland. Most of them still live there.

All the tents at the camp look identical, with white walls, a blue roof and little plastic windows. There are a few trees and everything is surrounded by sand.

“We are here, but that’s not what we truly want. We really miss the beachside,” said Sailo Boufal, a mother who has lived in the camp with her kids for four years, after their house was destroyed.

She said the relentless heat is the worst part of it.

“We don’t have electricity. We are already dead because of the heat, nobody can go in the tents before 10 p.m.”

Boufal said she doesn’t see a future for her family at the camp, even if the government builds new houses for them. So, she said she’s considering getting on a smuggling boat and trying to make it to the Canary Islands, in Spain, like many of her neighbors have already done.

And even though retired fisherman Badiane’s house was not destroyed at the time, he and his neighbors have received notice from local authorities warning them that they might also have to relocate soon.

Badiane said, though, that he’s reluctant to leave.

“We have decided to become a coalition and stand strong against the government who wants to take us away from here,” he said. “This is all we know, and all we have.”

But Mandaw Gueye, director of the Regional Agency for Development in Saint-Louis, said that in the next few years, about 15,000 more fishermen and their families are expected to move into the area close to the Diougop camp.

“Even if they don’t want to,” he stressed.

He said the government is building a more permanent housing solution there, and arranging to provide shuttle buses for fishermen to reach the coast.

There are also plans to build a new sea wall, scheduled to be completed by 2050, after previous ones failed to prevent floodwaters from reaching the village.

But that might be too late.

It’s estimated that in West Africa, over 40 million people in these lowest-lying zones, will be exposed to sea level rises by 2030 — less than a decade away.

Natural barriers at risk

Some of the biggest and fastest-growing cities in African countries are on the coasts and vulnerable to rising seas, said Mark Duerksen, a researcher with the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, and an expert on urbanization on the continent.

“It’s an open question whether they will all survive and find strategies to host all the people who want to live and work along these bustling shorelines.”

Frequent flooding, storms and coastal erosion are also destroying natural barriers like wetlands, coastal dunes and barrier islands, which create more vulnerability to sea level rise.

“This is compounded in many African cities where there are relatively weak environmental protections and significant shortages of existing and affordable housing,” Duerksen added.

The United Nations predicts that, over the next couple of decades, around 200 million people could be displaced as a result of flooding and shoreline erosion. The situation is particularly bad in West Africa, where a large percentage of the population lives on the Atlantic shore.

An important cultural legacy that is also threatened by rising seas in Saint-Louis is the city center — a UNESCO World Heritage site, full of colorful architecture, where important jazz and dance festivals take place every year. It includes historical buildings from the 19th and early 20th centuries, which could all disappear with the rising waves.

Local journalist Borso Tall contributed to this story.

Related: Is it time for Senegal to end its romance with the French baguette?

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!