‘It’s the new soccer, where stars are born’: Trap music boom inspires Argentine youth

Last spring, 24-year-old Kevin Villagra decided to quit his job at a vegetable store in Buenos Aires, Argentina, to pursue his dream career as a rapper in the country’s booming trap music scene.

“It’s the new soccer, where stars are born,” he said. “Things are moving really fast.”

As Latin American artists top the charts globally, Argentina has become home to some of the most successful music stars in the Spanish-speaking world.

A generation of singers and producers in their 20s have turned into global phenomenons by imprinting their own personality on pop, reggaeton, and hip-hop-inspired genres like trap.

The likes of Bizarrap, Duki, Nicki Nicole, and María Becerra have not only enchanted millions of listeners, but also inspired many in their home country to follow in their footsteps.

With Argentina mired in economic instability, some young artists see music not only as their passion, but also as an escape plan.

“I want to go all-in for something that could change my life, and get me, my family, and my loved ones out of this very unstable situation,” Villagra said.

Villagra grew up in Florencio Varela, a city south of Buenos Aires, and moved to the capital in his early teens when his father got a job as a janitor.

Villagra took voice lessons throughout his adolescence, and in recent years began recording his own music at home studios of friends.

He has released a handful of songs under the stage name “Keke,” racking up a few thousand plays on Spotify and Youtube, and is currently working on his first EP.

The artificial sound and downbeat energy of trap music is perhaps most present in his track “SUER7E,” which also features other stylistic staples of the genre like synthesizers, an electronic beat, and highly processed vocals with the help of autotune.

Most of Keke’s songs are collaborations with other artists and producers—which in itself is a key feature of the Argentine music scene.

As an example, the song currently at the top of Spotify’s Top 50 chart in the country is “Los del Espacio,” a collaboration between eight different Argentine artists.

“It’s beautiful how artists in the scene help each other out,” Amparo Legorburo, the co-host of the podcast “Musincronía,” from Uruguay, told The World.

Lyrics in Argentine trap are often aspirational, said Legorburo, dealing with one’s place of origin and hopes of a better future, as well as Argentines’ distinct national pride.

This sense of community is reinforced by the online presence of many artists, and their intensive use of social media platforms like Instagram, TikTok, Twitter and YouTube channels.

Trap has become the defining musical genre of present-day Argentina, just like rock nacional from the mid-1960s to the 1980s, or cumbia in the 1990s.

“These were all popular manifestations responding to their times in their own way,” said Diego Varela, co-host of “Musincronía.” He believes Argentine trap has already become a “very important milestone” not only in the country’s history, but also in Latin American music.

While the hip-hop subgenre of trap emerged in the 1990s in Atlanta, the birth of Argentine trap is often associated with the rise in popularity a decade ago of freestyle rap battles, most notably “El Quinto Escalón,” (Spanish for “The Fifth Step”).

El Quinto Escalón was held for the first time in March 2012, in the Rivadavia park in Buenos Aires, with very few people in attendance the first time, recalled Juan Goldberger, known as Juancín.

Goldberger went on to become one of the event organizers and has since released a 26-part video series about the history of El Quinto Escalón on his YouTube channel.

“Trap music exploded and became very popular thanks to El Quinto Escalón,” Goldberger said. “It became a platform where many people interested in hip-hop could develop themselves and gain exposure.”

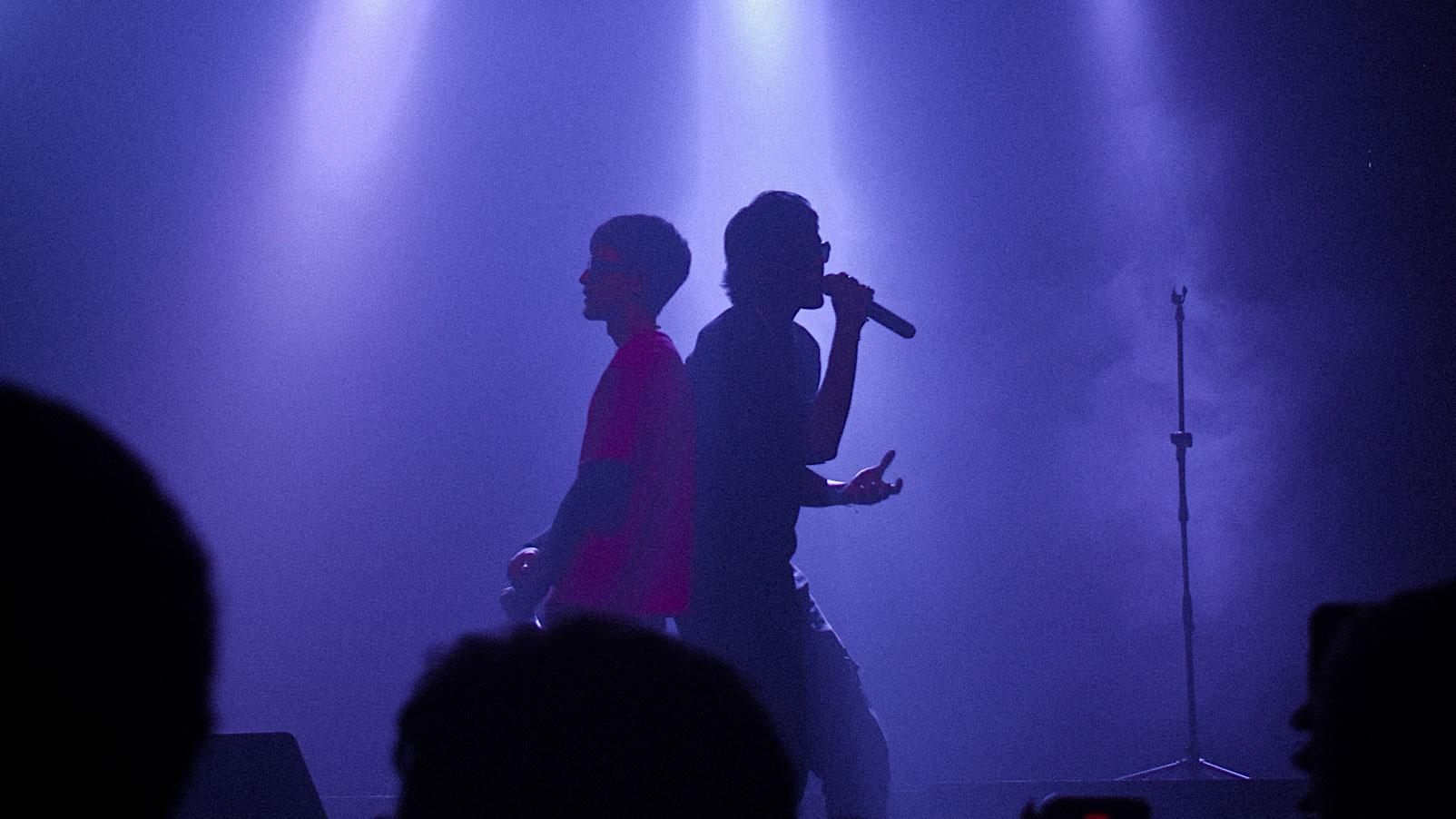

During battles, the rappers would take turns slamming at each other, while the public surrounded them and cheered at every jab — a scene Goldberger compared to Ancient Rome’s shows in the Colosseum.

“The energy of the public, the emotion, it was very intense,” Goldberger said. “With every rhyme, we knew we were witnessing something historic.”

El Quinto Escalón grew bigger, and bigger, attracting thousands of people to the Rivadavia park, while millions followed their favorite rappers online on the official YouTube channel.

By the time El Quinto Escalón ended, in 2017, a new music scene was emerging, with former competitors recording their own tracks, like “No Vendo Trap by Duki,” the song that according to Goldberger really kicked off trap music in Argentina.

Many other artists followed, meeting at the house of whoever had a computer, a microphone and speakers to make their own music.

“To make a trap song you need very little,” Goldberger said. “You can learn all the basics through video tutorials, download some beats from YouTube, turn on autotune and just record yourself.”

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?