From coal to airports to cooking oil, Gautam Adani’s businesses span the gamut. Until recently, the Indian business tycoon was Asia’s richest man and the third-wealthiest person in the world.

Last year, Adani even briefly surpassed Amazon founder Jeff Bezos to claim the spot as the world’s second-wealthiest person.

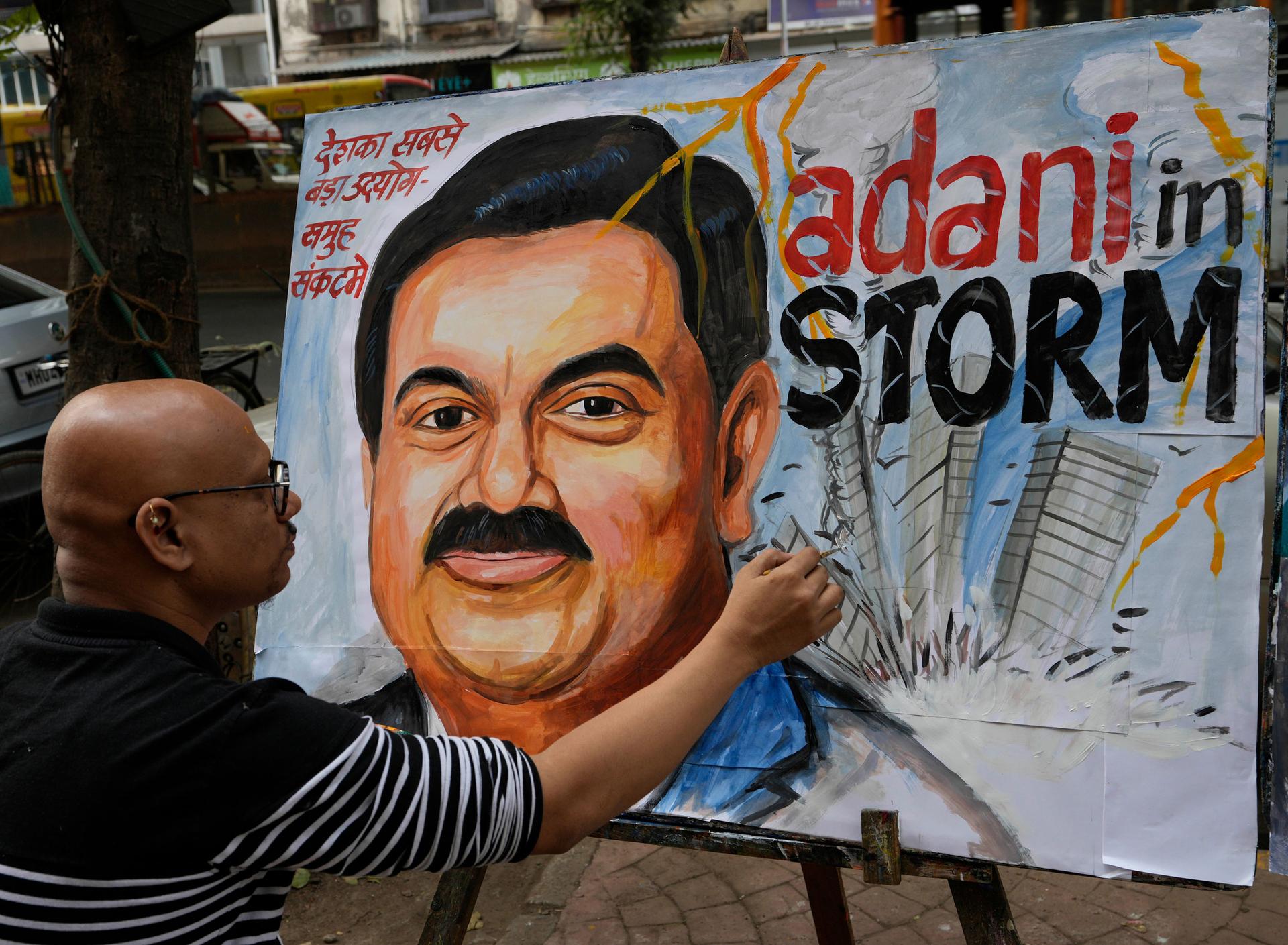

But earlier this year, a big chunk of Adani’s wealth — more than $50 billion — got wiped out in a matter of days. Adani’s stocks hurled into a free-fall after a New York-based short seller accused Adani of “pulling the largest con in corporate history,” with sweeping allegations of fraud and money laundering.

Since then, Adani’s companies have recovered partially but questions about his meteoric rise are still swirling. There’s also renewed scrutiny of Adani’s links to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and how their relationship may have fueled the businessman’s growth.

The rise of Gautam Adani

Born in 1962, Adani was the seventh child in a middle-class family in the western Indian state of Gujarat. When he was 16, he dropped out of school and boarded a train to India’s financial hub Mumbai.

“All I knew was that I wanted to do something different and do it on my own,” he said recently to a group of schoolchildren in his home state.

As a young man in Mumbai, he worked in the diamond business, eventually setting up his own brokerage after which he moved back to Gujarat to help his brother run a plastics business. Then, in 1985, when India liberalized its import policies, Adani started a trading company, mainly importing plastic, a move which “laid the initial foundation of the global trading business I was soon to build,” he said.

Today, Adani’s portfolio consists of gas, electricity, coal, renewables, ports, media and more. His projects span worldwide — from coal mines in Australia and Indonesia to a port in Israel. The Mundra port in Gujarat, India’s largest commercial port, is Adani’s crown jewel.

The Modi-Adani link

Adani and Modi hail from the same state and both come from humble backgrounds. They share a symbiotic relationship that goes back more than two decades, according to Jayati Ghosh, an economics professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

“You cannot imagine [Adani’s] rise without the political backing that he has got,” Ghosh said.

In 2002, when Modi was criticized for fomenting sectarian riots in Gujarat, Adani stuck by him.

“Mr. Adani made it very clear that he was still very much in support of Mr. Modi, and brought to bear not only his own support as a capitalist entrepreneur but mobilized others,” Ghosh said.

When Modi was elected prime minister in 2014, he flew to his inauguration in one of Adani’s planes. Later, Adani won bids to run six Indian airports despite having no experience in the sector. His wealth shot up, growing by about $100 billion in just the last three years. The Hindenburg research group released a report noting this impressive rise is no coincidence.

“We have uncovered evidence of brazen accounting fraud, stock manipulation and money laundering at Adani, taking place over the course of decades. Adani has pulled off this gargantuan feat with the help of enablers in government and a cottage industry of international companies that facilitate these activities,” the report said.

It also raised concerns about the high levels of debt in Adani’s companies.

Adani denies any wrongdoing and said that Hindenburg has vested interests because it is a short seller that is betting against Adani.

“The fundamentals of our company are very strong, our balance sheet is healthy and assets robust,” Adani said in a video released shortly after the Hindenburg report came out.

A savvy trader?

R. N. Bhaskar, who has written two books about Adani, said friendly relations between businessmen and the government aren’t unusual.

“In a developing country, you have to be close to your government,” he said.

Mukesh Ambani, another Indian billionaire businessman, is also known to have benefited from close relations with the government. Bhaskar pointed out that Adani has projects in many states where Modi’s party is not in power.

“He is good in implementation, he’s good in making profits. And he creates jobs,” he said.

According to Bhaskar, Adani’s success has come about not because of his affiliation with any politician but because of his business acumen.

“He’s the savviest of traders that I’ve come across,” he said. “His warmth and simplicity in relationships is appealing and his razor-sharp mind. People haven’t understood how sharp his strategic thinking is.”

Part of Adani’s strategy, Bhaskar said, is aligning his business interests with national interests. Adani often draws parallels between his own rise and that of India. When Hindenburg accused the Adani group, the company deemed it a strike against the nation.

“This is not merely an unwarranted attack on any specific company but a calculated attack on India, the independence, integrity and quality of Indian institutions, and the growth story and ambition of India,” the group said in a statement.

But Jayati Ghosh said that comparison is flawed: “In a sense, it’s also a form of hubris that you equate yourself with the nation and your own personal interests with the national interest,” she said. “It’s also essentially authoritarian.”

In reality, she said, India is “one of the most-unequal economies in the world.”

India’s age of billionaires

While Adani’s wealth is impressive, he’s not alone. The country added 64 new billionaires in just the last two years, according to Oxfam. Political observers often compare today’s India to the United States to the Gilded Age of the 19th century, with its robber barons.

India resembles an oligarchy, Ghosh said, where a few large capitalists “are controlling more and more of India’s assets and productive structures, some because of their own expansion, but largely because of the sale of private assets and public assets, which they have been able to get larger and larger shares of.”

For the majority of the population, conditions have gotten worse in recent years, she said.

“If you look at real wages, they have been stagnant or declining. And a very small segment, the top 10% and within that, the top 1% and within that the top 0.1% have absolutely ballooned in wealth, assets and incomes,” she said.

India’s Supreme Court is now looking into whether or not Adani’s burgeoning wealth came about unfairly, including the establishment of an independent panel to probe allegations made by Hindenburg.

But R. N. Bhaskar said the tycoon remains unfazed.

“He’s not bothered. He’s going to continue his own plans,” he said. “He’s not shriveled in any way.”

Adani has welcomed the Supreme Court’s investigation, saying that “truth will prevail.”