The COVID-19 pandemic has killed about 7 million people worldwide but the true tally is likely much higher. Beyond COVID-19 casualties, the pandemic has also weakened health care systems around the world, and interrupted other available care, from cancer treatments to routine vaccinations.

As a result, the global life expectancy has dropped by an average of about two years — the first such reduction since World War II.

Dr. Atul Gawande has been trying to bring global health care back on track. He’s a renowned surgeon, writer and researcher who now heads global health at the US Agency for International Development.

“We have gotten ourselves out of the emergency.” he told The World’s host Carolyn Beeler. “Thanks to a combination of vaccines, natural immunity — 90% of the world has gotten infected — and, add to it that we also have antiviral treatments that also provide tremendous protection.”

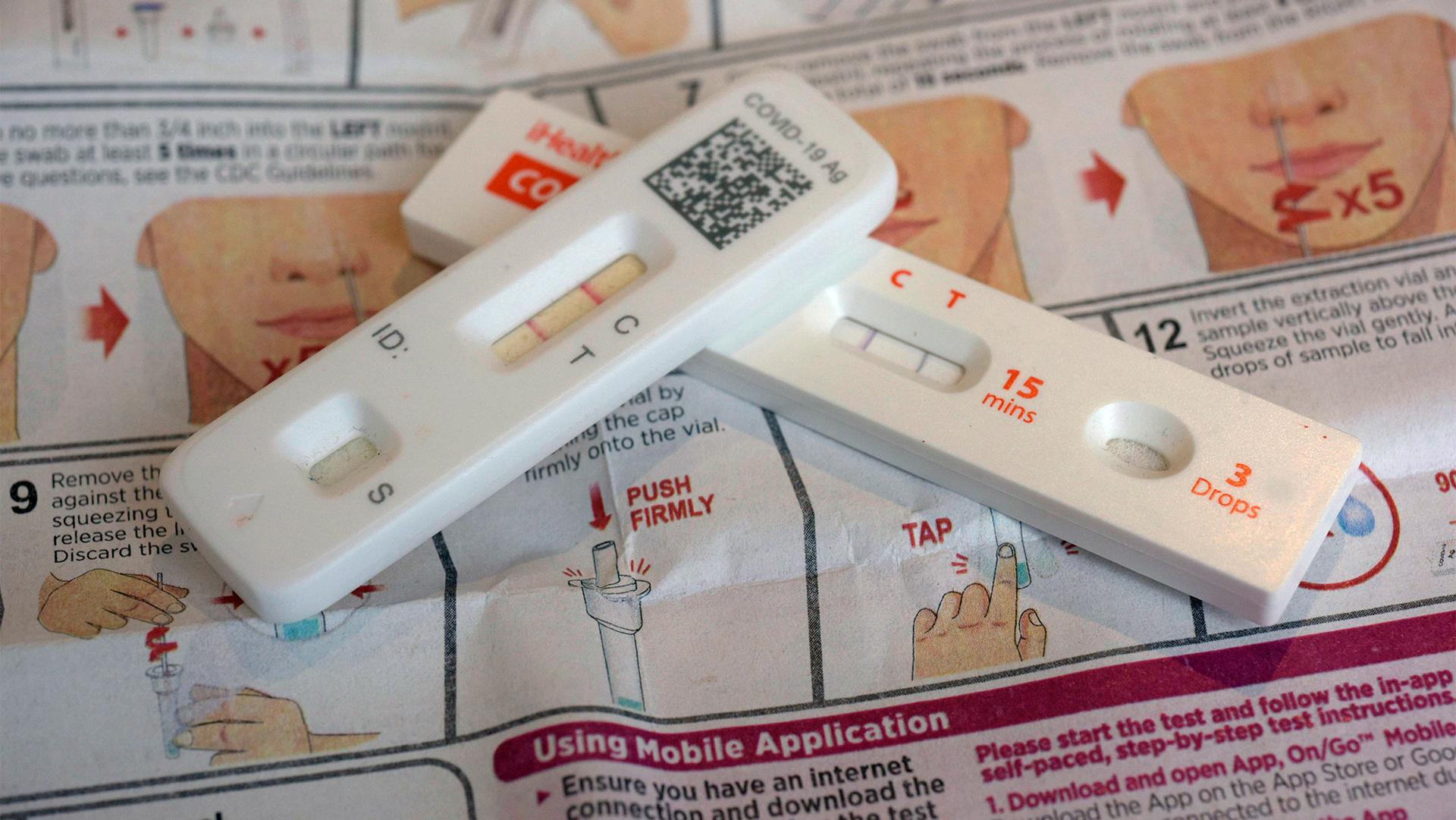

US President Joe Biden signed a bill on April 11 that officially ended the COVID-19 national emergency in the United States. Another public health emergency is also scheduled to end on May 11.

“Recovery from the pandemic will require as much focus and attention as it did when it first started.”

But, Gawande explained, “we now have an endemic disease that’s a top-10 killer in the world, which means that recovery from the pandemic will require as much focus and attention as it did when it first started.”

In addition to deaths from the virus, setbacks to health care systems and the global economy have also contributed to lower life expectancies, especially in low- and low-middle-income countries. Wealthier countries were able to borrow against their budgets to stay afloat. Those countries are now facing debt distress, with cuts to financing and workers within their health systems.

Success stories

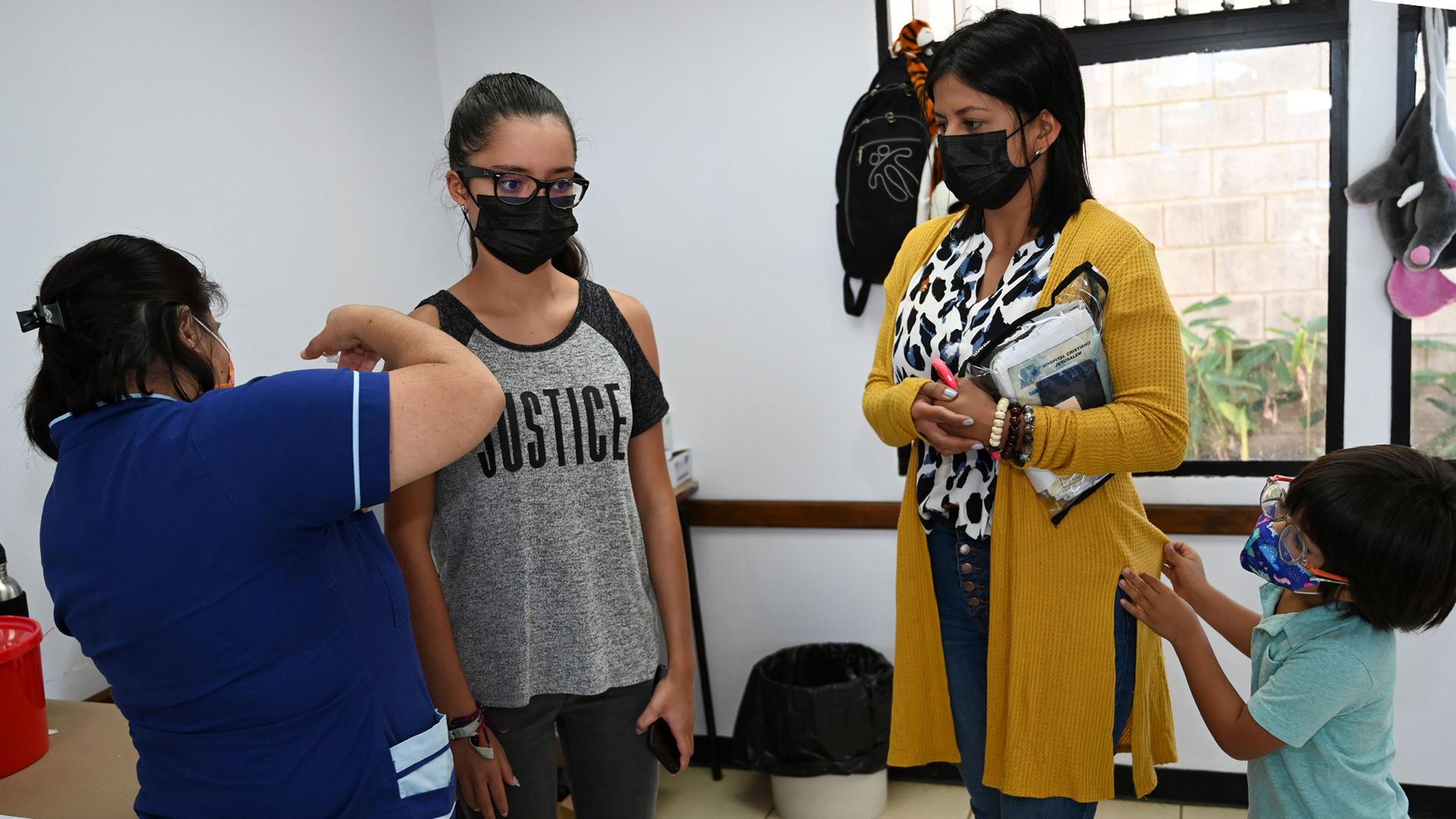

Some smaller economies, however, have prevailed, including in Costa Rica and Ghana. Life expectancy in Costa Rica is now over 80 years — even higher than in the US.

“Their primary health care system enables there to be community health workers who visit every home at least once a year to assess the health needs the family has and make sure they’re not falling through the cracks,” Gawande explained.

When COVID-19 vaccines came around, it was easier to schedule appointments for everyone. Whereas in the US, the “health system is set up for people to come into it, but not to do outreach.”

Gawande said he knows first-hand about the necessity of good health care system. His paternal grandmother died many years ago of malaria. Treatment was available — but hadn’t reached places like her village in Nagpur, India.

Gawande’s father saw how advanced knowledge and training could deliver new health outcomes, but his community did not yet have the infrastructure or resources to afford it. He went on to receive medical training in Ohio, in the United States and is now a doctor. Today, his village has primary care physicians, an anesthesiologist, an obstetrician, a general surgeon, along with public health capabilities that weren’t there before — and they’ve pushed India’s life expectancy to beyond 70 years.

Related: ‘The pandemic is still with us’: The bumpy road to the end of COVID

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. Click above to listen to the entire discussion.