The Philippines is among the most dangerous places in the world for environmental activists

Environmental activist Windel Bolinget remembers what it was like to end up on a government list for the first time.

It was 2018 and his name was included on a petition to designate the Communist Party of the Philippines a terrorist group — he wasn’t even a member of the group.

“My name was just included there,” said Bolinget, an Indigenous Igorot and the chairperson of the Cordillera Peoples Alliance. “There were more than 600 names just deliberately included there as terrorists.”

This happened, he said, because of his activism in opposing development projects in the Cordillera region — a mountainous, landlocked area on northern Luzon Island, the Philippines’ largest island.

The country has long been one of the most-dangerous places in the world for environmentalists. The international nonprofit Global Witness has, for years, ranked the Philippines in the top slots of its annual list as deadliest countries to be an eco-activist. Dozens of environmentalists and land defenders also die each year.

“In the Cordillera, our ancestral domains are targeted for big hydropower or dam projects, large-scale mining,” Bolinget said. “And our communities are resisting these projects because it violates our collective rights to our ancestral lands.”

Although Bolinget’s name, and hundreds of others, were eventually removed from the petition, the intimidation against them continued.

In 2020, Bolinget was falsely accused of murder and a warrant was issued for his arrest. A manhunt ensued and a shoot-to-kill order was placed on his head. The whole thing was completely fabricated, Bolinget said, which is how his lawyers were again able to get the warrant dropped.

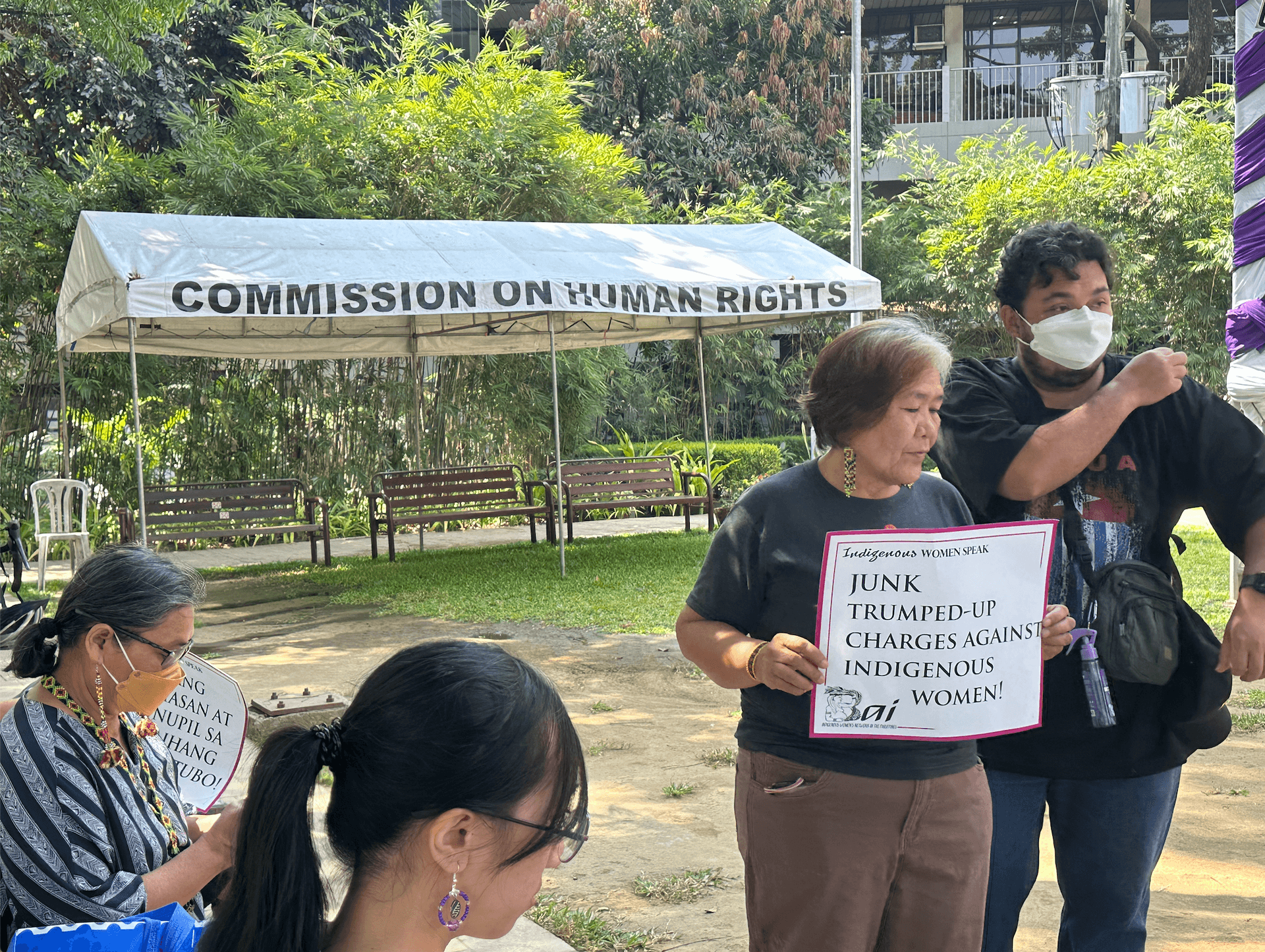

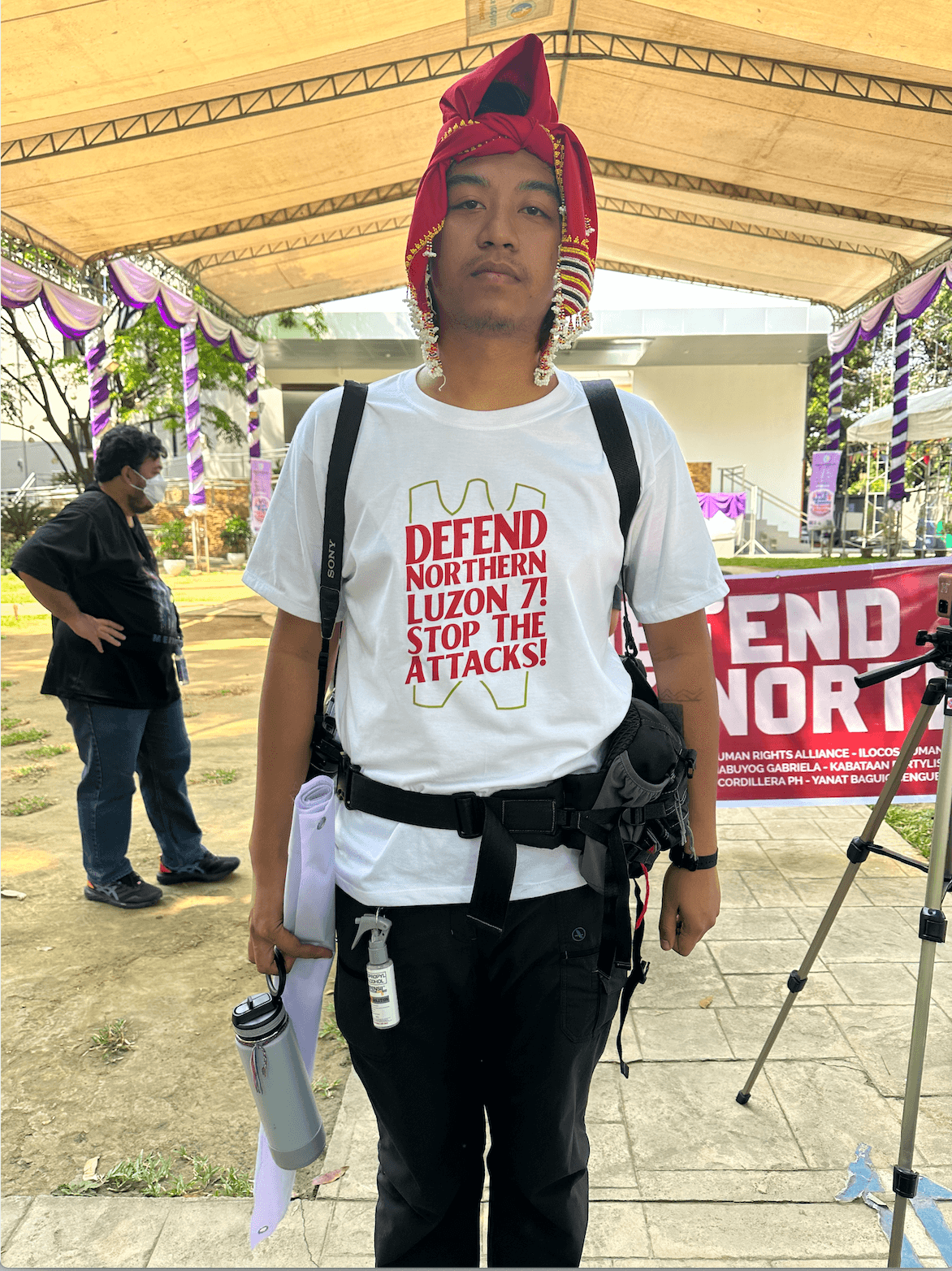

But earlier this year, another arrest warrant was issued. This time, for Bolinget, five other Indigenous activists and a community journalist — all from northern Luzon.

“We are called the Northern Luzon 7, charged with rebellion or insurrection,” he said. “Again, there was no due process.”

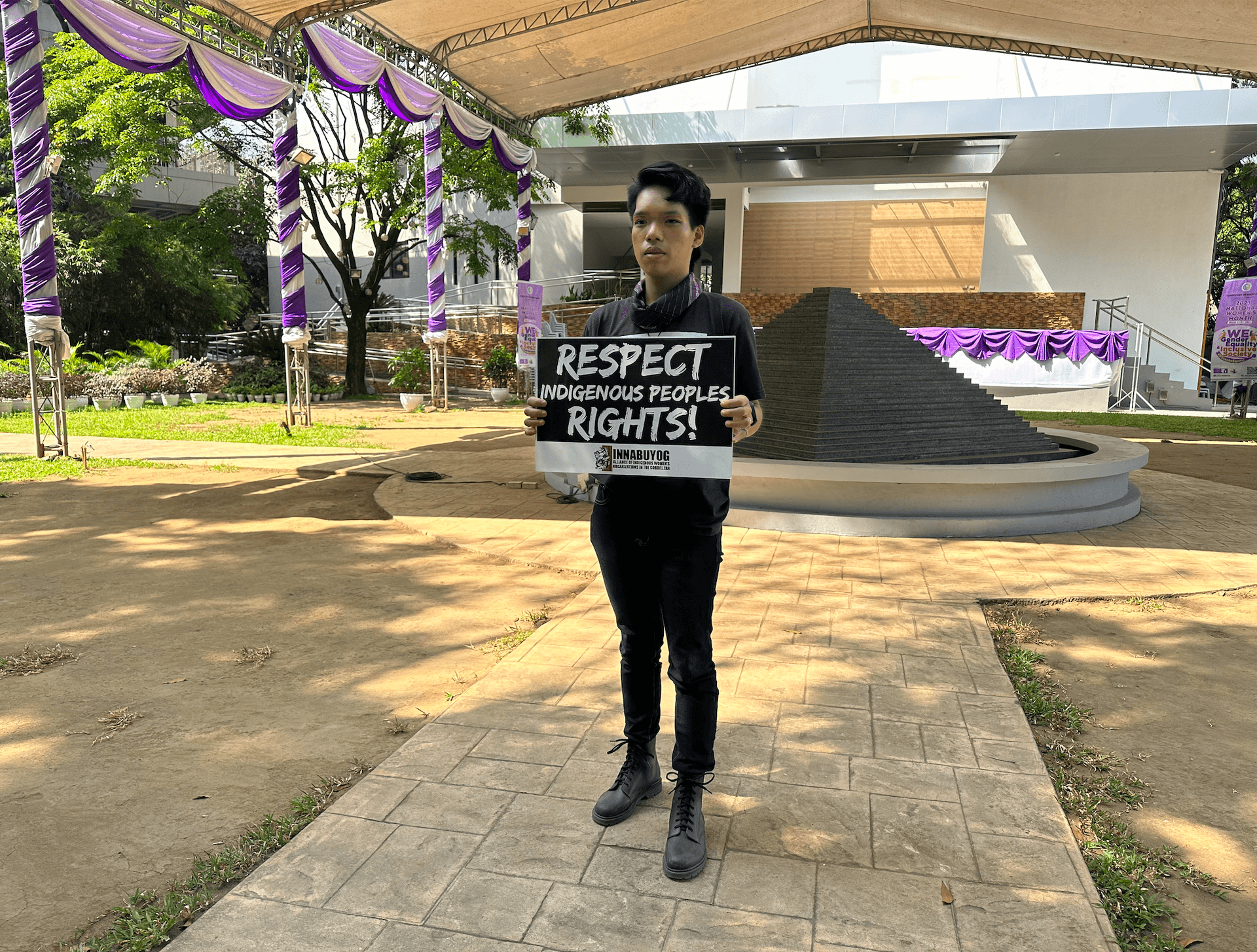

Currently, the seven are out on bail. Bolinget and others traveled to the capital, Manila, last week to tell the government about their experiences, as well as to bring up the recent spate of bombings happening in the Cordillera region.

Since early March, people there have reported that up to nine bombs were dropped near their communities. Bolinget said this has disrupted their economic livelihoods and “brought terror.”

He added that he is afraid, but remains defiant.

“Of course, that’s normal for a human being [to be afraid], but their intent is to silence us. But what we are doing, it’s our duty. We cannot be silent. We owe this to our children.”

‘Development aggression’

The struggles of environmental activists in the country go back decades, explained Carlos Conde, a senior researcher with Human Rights Watch based in Manila.

There was a term for it in the 1970s: “development aggression.”

“This mainly refers to development projects that tend to displace environment and Indigenous people’s communities,” Conde said. “And this has resulted in conflict.”

He said that much of the conflict stems from the government ignoring the requirement to get consent for projects from Indigenous communities called the Free, Prior and Informed Consent: a guiding, international human rights principle that basically says governments must consult and work with Indigenous communities before making decisions — such as building developments — that affect them.

“That’s why, now, with the Philippine government and national security’s establishment, basically, they’re targeting Indigenous people’s communities. But in many instances, these Indigenous people’s communities who are against the project are not necessarily insurgents.”

Conde said there is middle ground between development that the country sorely needs and the rights of Indigenous communities, but it comes down to the government making a deliberate effort to listen to them.

‘We are not anti-development’

The current administration of President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. has so far been silent on both the Luzon 7 and recent bombings.

Some analysts say that’s just part of keeping up the facade that Marcos has united support in the north, where he hails from. His home province Ilocos Norte is a picturesque place where the Cordillera Mountains meet the waves of the West Philippine Sea.

It is also rich in natural sources, both on the land and in the sea, said activist Genaro Dela Cruz, who is from the same province and is head of the Ilocos Human Rights Alliance.

“Illocos Norte actually was named as the center for renewable energy in Southeast Asia, not only in the Philippines, because of the windmill and solar farms that generate electricity.”

But these developments threaten the communities there, said the veteran environmental activist, who has also experienced harassment by authorities for his activism.

Dela Cruz said the idea that activists are against development is a misunderstanding.

“We are not anti-development, but we want to put up development projects for the people and not for a few ones, or the rich ones.”

He said he hopes that including his community in conversations about development will ensure the projects benefit everyone.

Related: Record-breaking inflation rates in the Philippines are pushing people to take on extra jobs